Rookwood Cemetery, old Chinese section. (Source: Anne Tsang}

This year for History Week 2018, the theme was ‘Life and Death’, celebrating the monumental milestones of a person’s life. One area we looked at was Chinese death rites. The Chinese culture is rich in customs, traditions and superstitions.There is a is a strong belief in life after death and spirits. Death is seen as not the end, but only a metamorphosis – the beginning of another life. Thus the need for ancestor veneration, that is, paying respect to one’s ancestors through setting up ancestor altars and shrines at home as well as visiting graves on certain occasions based on the Chinese lunar calendar to worship as an act of filial piety (孝子 xiào zi).

There is a Chinese proverb that says “To forget one’s ancestors is to be a brook without a source, a tree without a root.”

Honouring the Spirits

Every year, there are many Chinese festivals associated with death. Those commonly practiced by the Chinese community today include:

-

Qing/Ching Ming or Tomb-Sweeping Day 清明節

Also known as Chinese Memorial Day or Ancestors’ Day. This is a traditional Chinese festival that has been practiced for over 2,500 years. It usually falls on the 15 day after the Spring Equinox, either 4 or 5 April in a given year. Next year it will be on 5 April 2019. During Qingming, Chinese families would visit the graves of their ancestors to clean the gravesites, pray to their ancestors, and make ritual offerings. Offerings would typically include traditional food dishes, and the burning of joss sticks and joss paper – paper money and other paper articles to help the spirit in the next world. In some places, firecrackers may be lit to scare away evil spirits. -

Yulan or (Hungry) Ghost Festival 盂蘭盆節

Hungry Ghost Festival (Yulan Festival) is practiced on the 15 day of the seventh lunar month (also known as ‘Ghost Month’). It is a time when makeshift roadside altars glow with burning joss paper and when the living do everything they can to appease and pacify wandering spirits – restless ghosts of strangers who died of unnatural causes such as murder or suicide or those who did not get a proper burial. During Ghost Month, the Chinese believe that the gates to the underworld are opened on the first day of the seventh month on the lunar calendar and so restless ghosts come out to wreak havoc on the living until the gate is close again on the last day of the month. To pacify these hungry ghosts, the living observe superstitions and make offerings of food, money and entertainment all month long, culminating with an outdoor ghost-feeding ceremony on the night of the Hungry Ghost Festival. It’s believed that content ghosts won’t cause trouble, especially for those among the living who faithfully serve them. -

Ninth or Chong Yang Festival 重陽節

A time for communicating with the dead on the 9 day of the 9 lunar month. At this time it is possible to appease the wandering spirits of people who have not died a natural death or have not been accorded ancestral worship. Paper money and clothing are burnt in the cemetery burners and a grand feast is organised so that wandering spirits are properly fed and clad and are not tempted to claim a living substitute as a resting place.

Death Rituals

Death especially funeral and burial customs vary among the Chinese people. There are currently 56 ethnic groups officially recognised by the Chinese government, thus ethnicity and location – where the person died (in China or overseas) and where regionally the deceased’s home or ancestor village is from are elements that dictate death rituals. For example, the Southern Chinese from regions such as Guangzhou Zhou or Canton will practice reburials whereas Northern Chinese will omit this practice. Cause of death, age and marital status of the deceased, his/her wealth, status and position in society, religious faith and family wishes are all important factors that influence how contemporary Chinese people may carry out funeral and burial proceedings. A geomancer, feng shui and Chinese almanac may also be consulted during the process.

It is believed that improper funeral arrangements can wreak ill fortune and disaster upon the family of the deceased.

Chinese funeral rituals comprise a set of traditions broadly associated with Chinese folk religion, that blends elements from Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and shamanistic beliefs. Confucianism provides the moral code or ethics of behaviour found in its authoritative books known as the Four Books and Five Classics (四書五經 Sìshū wǔjīng) which includes the Book of Rites (禮經 Liji) written before 300 B.C. in China. Taoism is considered both a religion and philosophy emphasizing the independence of the individual and connection to natural forces of life; and Buddhism contains the rituals of the spiritual life (Penson, 2004; Picton & Hughes, 1998).

Funeral Proceedings

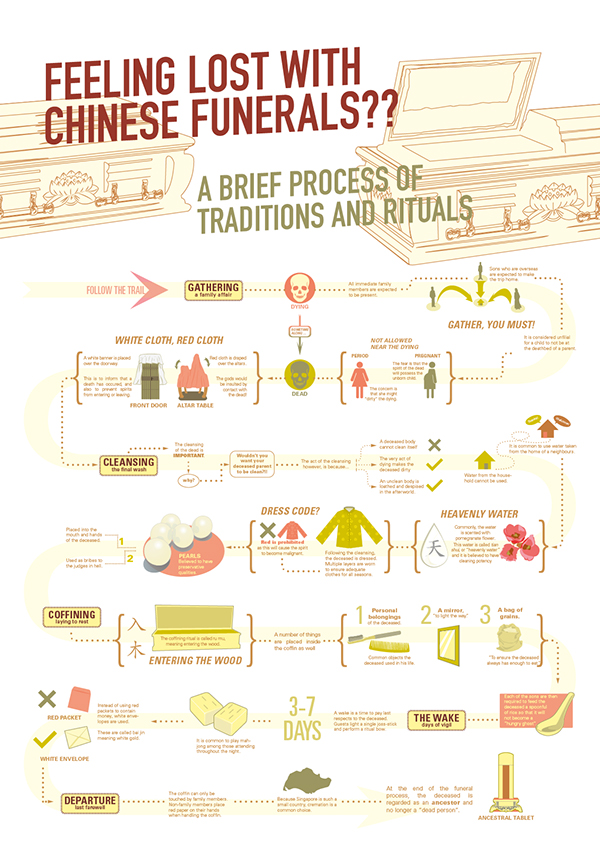

A brief process chart traditions and rituals for a Chinese funerals (Source: Victor Goh)

Funeral Etiquette

Burial or Cremation

Traditionally, inhumation or burial in the ground is very common. However, when Mao Zedong came into power and formed the People’s Republic of China in 1949, cremation and memorial meetings were made the norm to replace the traditional funeral rites which was branded as “feudal superstition” and burials a waste of arable land while coffins a waste of wood during Maos’ era. Today China has one of the highest cremation rates in the world. Other than inhumation and cremation, “water burial”, “open burial” and “hanging-coffin burial” were also practiced in ancient China and due to overcrowding, eco-friendly burial practices are gaining traction.

Falling Leaves Return to their Roots

The death of a Chinese person while overseas complicated the natural order of death ritual and worship. During colonial periods, many Chinese, like ‘falling leaves’ returned or tried to return to their roots in China before death. However, if they died overseas, extraordinary measures were taken to bury the Chinese in an appropriate manner that closely followed a traditional Chinese funeral which also accommodated the host culture. Commonly many Chinese were buried in foreign soil for about 7 years before their bodies were exhumed and their bones placed in urns for reburial in their home village in China. One physical manifestation of these activities is exhibited in Chinese cemeteries and burials throughout the world as shown in the photo from the top of the old Chinese section of Rookwood Cemetery near Lidcombe train station. The emptiness is a result of many graves being exhumed and subsequently sent back to China. We know this based on records in the archives, newspaper accounts published, and oral histories/family legends. Tombstones, ritual burners, altars and artefacts help document the lives of the overseas Chinese.

Changes in funeral and burial practices can also be seen throughout the history of China starting with the Imperial family and down to the common person. Temples and shrines are built to worship the dead to show filial piety.

Anne Tsang, Research Assistant, City of Parramatta, Parramatta Heritage Centre, 2018

References

- Abraham, Terry, and Priscilla Wegars. (2003). “Urns, Bones and Burners: Overseas Chinese Cemeteries.” Australasian Historical Archaeology, vol. 21, pp. 58–69.

- Australian Museum. (2009). Ching Ming at Rookwood. Retrieved 18 August 2018 from https://australianmuseum.net.au/image/ching-ming-at-rookwood

- Bell, Peter. (1996). “Archaeology of the Chinese in Australia.” Australasian Historical Archaeology , vol.14, pp. 13–18.

- Chang Yong (1919, November 3). Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 – 1931), p. 3. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115876824

- China Highlights (2018). A grave day–the culture of death! Retrieved 7 August 2018 from https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/article/death-culture.htm

- Chinese-Australian Historical Images in Australia. (2013). Death and burials. Retrieved 18 August 2018 from http://www.chia.chinesemuseum.com.au/biogs/CH00045b.htm

- Couchman, Sophie, and Kate Bagnall. (2015). Chinese Australians: Politics, Engagement and Resistance. BRILL.

- Evergreen Mortuary & Cemetery (2018). Chinese Funeral Traditions. Retrieved from https://www.evergreenmortuary-cemetery.com/layout/uploads/chinese-funeral-traditions.pdf

- Goh, Victor. (2013). Chinese funerals – process charts. Behance. Retrieved 20 August 2018 from https://www.behance.net/gallery/9992617/Chinese-Funerals-Process-Charts

- Hill, Ann Maxwell. (1992). “Chinese Funerals and Chinese Ethnicity in Chiang Mai, Thailand.” Ethnology, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 315–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773423.

- Hsu, Chiung-Yin, Margaret O’Connor, and Susan Lee. (2009). “Understandings of Death and Dying for People of Chinese Origin.” Death Studies, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 153–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180802440431.

- Hunter, David. (2010, October). “The Archaeology of Chinese Funerary Practices in Colonial Victoria.” Hunter Geophysics, pp. 1–6.

- La Trobe University. Asian Studies Program. (no date). Chinese Australia: Death and burial in Australia in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Retrieved 5 August 2018 from https://arrow.latrobe.edu.au/store/3/4/5/5/1/public/FMPro7e48.html?-db=background.fp5&-format=format/background_record.htm&-lay=web&id=45&-max=1&-find=

- Liu Feng Shui. (2007-2018). Burials. Retrieved from https://www.liu-fengshui.com/services/burials

- Mitchell-Innes, Norman G. (1887). “Birth, Marriage, and Death Rites of the Chinese.” The Folk-Lore Journal, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 221–45.

- Nemo, Jary. & Wind & Sky Productions. (2016). Burial traditions. Culture Victoria. Retrieved from https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/immigrants-and-emigrants/many-roads-chinese-on-the-goldfields/ceremony-duty/burial-traditions/

- Perram & Timmins funerals. (2016). Chinese funerals Sydney. Retrieved 18 August 2018 from http://perramandtimmins.com.au/cultural/chinese-funerals-sydney/

- Theobald, Ulrich (2000). Liji 禮記. Retrieved 20 August 2018 from http://www.chinaknowledge.de/Literature/Classics/liji.html

- Waters, Dan. (1998). “Tracing Graves in Hong Kong: Research Methodology.” Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 38, pp. 395–98.

- Watson, James L., and Evelyn S. Rawski. (1990). Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China. University of California Press.

- Wegars, Priscilla. (2003). “From Old Gold Mountain to New Gold Mountain: Chinese Archaeological Sites, Artefact Repositories, and Archives in Western North America and Australasia.” Australasian Historical Archaeology, vol. 21, pp. 70–83.

- Wagner, Richard. (2014, December 4). Chinese funeral etiquette. The Amateur’s Guide To Death & Dying. Retrieved 13 August 2018 from http://theamateursguide.com/chinese-funeral-etiquette/

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018). Ancestor veneration in China. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 August 2018 from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ancestor_veneration_in_China&oldid=871751295

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018). Chinese funeral rituals. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 August 2018 from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chinese_funeral_rituals&oldid=871075855

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018). Double Ninth Festival. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 August 2018 from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Double_Ninth_Festival&oldid=871230120

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018). Four Books and Five Classics. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 20 August 2018 from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Four_Books_and_Five_Classics&oldid=865601770

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018). Ghost Festival. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 August 2018 from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ghost_Festival&oldid=871899129

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018). List of ethnic groups in China. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 August 2018 from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_ethnic_groups_in_China&oldid=869348206

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018). Qingming Festival. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.Retrieved 20 August 2018 from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Qingming_Festival&oldid=869465566

- Yeo, Teresa Rebecca. (2018). Chinese death rituals. National Library Board Singapore. Retrieved 20 August 2018 from http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2015-11-30_175737.html

- Young, Faye, and Nicole van Barneveld, eds. (1997). Sources for Chinese Local History and Heritage in New South Wales. F. Young.

Further resources

- Liu, Jun. (2017, March 5). Happy Weekend: How Chinese funeral culture in Australia. SBS Mandarin. Available online https://www.sbs.com.au/yourlanguage/mandarin/en/audiotrack/happy-weekend-how-chinese-funeral-culture-australia

is really talking about the Chinese funeral rites in different aspects but not only the Buddhist funeral rites. Appreciate that you even mentioned Liji.