Following the end of the Great War thousands of memorials were erected in suburbs and country towns across Australia. The world had witnessed death and destruction on a scale never before seen with many Australian families affected by a tragedy, loss, or wounding of a family member. In response communities and government rallied to create memorials to act as focal point for remembering the sacrifices made and to display pride in the soldiers lost in war.

The Prince Alfred Square Memorial was erected to remember those from the Parramatta district that had served and fallen in WW1. But behind the smooth, noble, and sombre facade of the obelisk lays a story of its inception, design, and location that speaks of a community’s voice, their debate and involvement, as well as the growth of a local council.

The idea to erect a monument to commemorate those from the Parramatta district who served in the Great War formally took hold following a meeting of the Peace Celebration Committee on 19 March, 1919. A number of proposals were put forward, the most popular being;

1. A monument to be erected in a prominent place in Parramatta to honour those who left the district to fight in the war

2. A memorial hall, to be utilised as a club for returned soldiers, an idea favoured by the Returned Soldiers and Sailors Association

3. A peace nurses’ home advocated by Dr Waugh

4. The Town Clerk’s improved town corner, Western Road and Church Street

5. New band stand and improvements to the amphitheatre at Parramatta Park

It was even suggested that the Centennial Fountain be converted to a memorial.1

The Peace Committee on 10 June 1919 which was entrusted with the arrangements for raising funds for a memorial for Parramatta, “… selected the scheme to place a monument worthy of the great sacrifice made by our local boys in suitable position in St Johns Park, and…decided to appeal for subscriptions wherewith to carry out this very desirable object.” 2

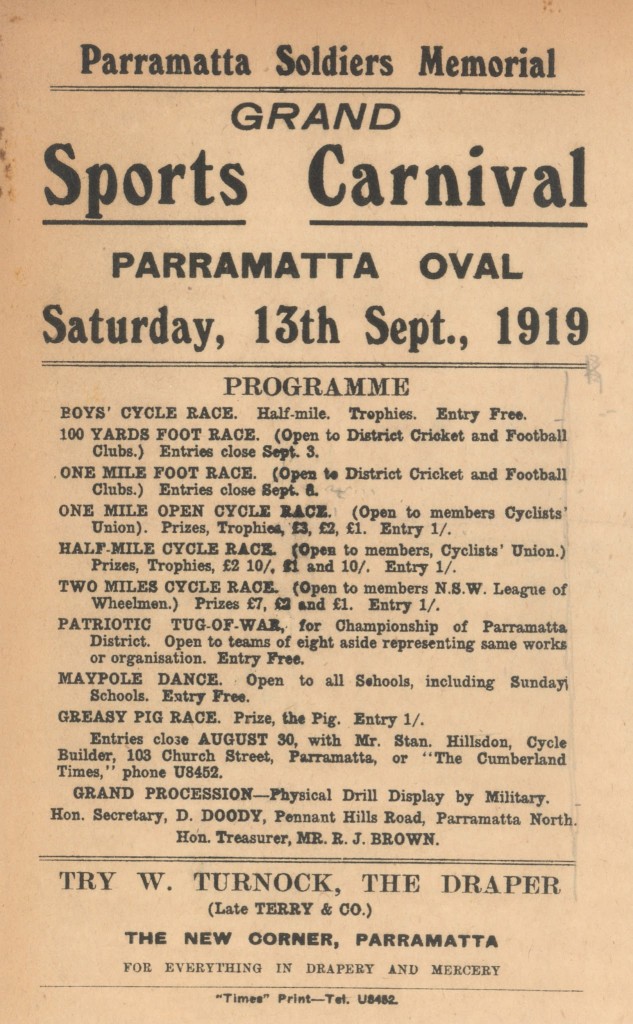

Fund raising was embraced by the community to support this cause. To raise funds for the memorial a range of events were organised including, among many, a Parramatta Soldiers Memorial Grand Sports Carnival in September 1919, a concert in November 1919 organised by girls from the Parramatta Industrial School with the assistance of local artists, a Soldiers’ Memorial Carnival that ran for a fortnight in March 1920 and raised almost 900 pounds, and a performance of the “Counsel for the Defence”, a comedy performed at Parramatta Town Hall in July 1920.

The selection of a memorial design was entrusted to a Committee representing business, Council and the community interests. In September 1919 public notices began to appear in the local papers calling for competitive designs for a soldiers’ memorial and honour roll for Parramatta. Expressions of interest were received from artists and companies including Fredrick W. Tod, the Wunderlich Company and Percy Calve.

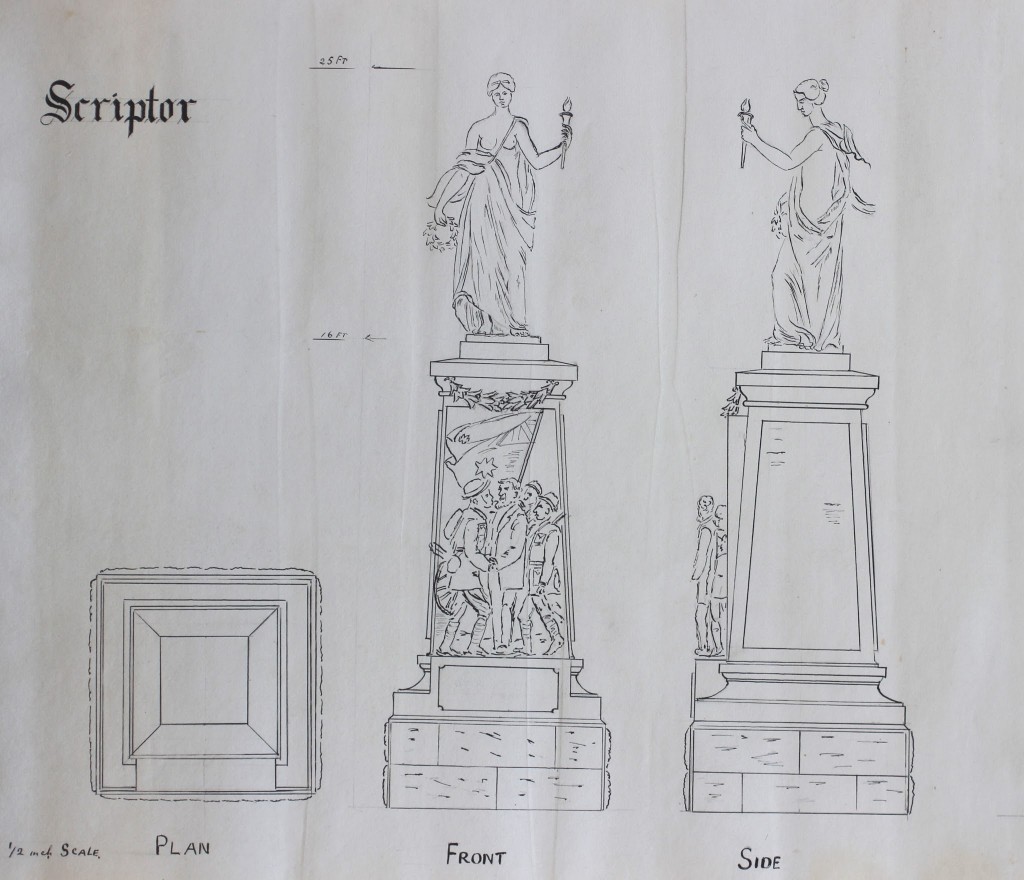

It appears however that none of the designs met with the approval of the committee. A fresh call for designs was made and in September 1920 the Committee made its selection, choosing the design submitted by well-known Sydney architect, Mr Roscoe J. Collins, a returned soldier from Manly. The design was described as “a very striking one. The memorial when erected will have a height of 36 feet, with a circular base of 32 feet diameter. The column, which will be of polished granite, will have sections of some other colour inlaid. In which will be inscribed in gold letters the principal centres of engagements, such as Gallipoli, Egypt, Pozieres, etc.”3

One of the unsuccessful designs submitted in the memorial design competition Parramatta Council Archives. PRS30/37/05

It might have appeared at this point that there was little more to be done for the memorial to be erected. Sufficient funds to begin construction had been raised, a design had been selected and there was a general consensus that the memorial would be erected at St Johns Park. However, while St Johns was the favoured site by most of the community it was not the site favoured by the Department of Local Government. The newly enacted Local Government Act of 1919 had taken the power of deciding on monument design and location away from Local Council and put it into the hands of the Minister for Local Government. The Minister had referred the matter of the monument and the site for consideration to the Public Monuments Advisory Board. The Board visited the site in May 1921. After visiting various sites in Parramatta and talking to officials they decided that the St Johns site was too small and suggested either Parramatta Park near the Boer War Memorial or the creation of a new square in the vicinity of the Centennial Fountain.4

From the inception of the idea for a memorial the site was a vexatious and emotional question. The community had debated for three years over the most appropriate site only to be overruled by State Government authorities. Still Parramatta insisted that the memorial be erected at St Johns. The general feeling of the people of Parramatta and district was this was their memorial and it was they who should decide on where it should be and what it should look like. It was a real test of the resolve of the Department of Local Government and the strength of the Act to ensure it stood firm with its decision not to have the memorial at St Johns against the protestations of the Council and community.

After three visits by the Advisory Board to Parramatta, Mr G Cann, Minister for Local Government, firmly stated the reasons for his decision. The principal reasons why the monument could not go ahead were that the monument could only be seen from one end; it would clash with the historical church behind it and with the fountain and; did not provide sufficient space for the holding of memorial services.5

By August 1922 supporters for the St Johns site had finally relinquished their battle. A number of emotionally charged meetings among subscribers were held to agree to an alternative site. Subscribers had given money for the erection of a monument at St Johns Park and Council felt tied to this decision. In a meeting held in September 1922, Dr Waugh, proposer of the Nurses home since as early as 1917, once again pushed for a nurses home memorial. A motion was put forward that the monument be erected at Parramatta Park. Mr Lilley moved an amendment that it be erected at Prince Alfred Square. Alderman Brown pointed out that Prince Alfred Square was under the control of the Council and it had already started to improve it. The placement of the memorial there would provide further incentive to improve the park and make it an “attractive beauty spot”. Alderman Noller still believed that Parramatta Park was the better location and that Parramatta Park would become the centre of a city. The meeting decided on Prince Alfred Square dependent on the approval of the Minister.6

The Public Monuments Advisory Board approved of Prince Alfred Square site but recommended that amendments be made to the original design before approval for the monument could be made.

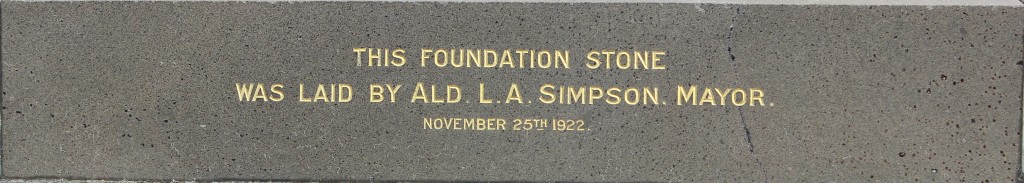

With a sense of finality the Committee moved on to approve the laying of the foundation stone, to be done before the end of Mayor Simpson’s term. On the 25 November, 1922, in the presence of a large crowd, the Mayor of Parramatta laid the foundation stone. “I feel highly honoured,”‘ said the Mayor, “at being given the privilege of laying the foundation stone of this memorial, which is being erected by the people of Parramatta, to commemorate the gallant deeds of our soldiers. The erection of this obelisk is not for the purpose of stimulating the spirit of war….” the Mayor continued, “When our men left these shores to uphold the honour of our traditions, it was impressed up on them that the slogan was ‘England expects every man to do his duty.’ But where lies the duty now? The men have done their duty, and it is now for us to do ours. I am afraid we are apt to forget; we are apt to look upon those deeds as past history, and treat them as past history.”7

The laying of the foundation stone did not lay to rest the controversy relating to the memorial. Two months after the laying of the foundation stone debate still raged over whether to include the names of only those who died or all the names of those who enlisted locally. The local Returned Soldiers League had strenuously objected to any names being inscribed on the monument. The Committee and subscribers were for the inclusion of the names of only those who had died. Major-General Cox was strongly of the opinion that all names should be inscribed.8

It was decided, mainly based on the costs of inscribing names, that only the names of the fallen were to be inscribed on the monument. The names of those who left Parramatta though, would be inscribed on vellum, and placed in a casket in the monument, where they would remain for all time.

On the 12 May 1923, in front of a crowd of 5000, Governor General Forster, accompanied by Lady Forster, unveiled the memorial. Lord Forster “expressed the hope that neither the monument nor the ceremonies of the afternoon would engender the belief that such a memorial would be likely to foster and develop a spirit of militarism among the young and future generations. The monument was not Intended merely to signalise a triumphant victory, but to serve as a tribute of gratitude and appreciation of the gallant and self-sacrificing service rendered by Australia’s brave sons and daughters.”9

Lady Forster placed within a cavity of the obelisk a parchment roll upon which were inscribed the names of all Parramatta soldiers and sailors who had served during the Great War.

This Monument has since been dedicated to those who had served in World War Two, Malaya, Korea, Borneo, and South Vietnam. It remains a gathering point for ANZAC day Memorials. It has and will perhaps always be a reminder of the effects of war, but at another level this memorial, through its history of how it came to be – the community involvement, fund raising through public subscriptions and events, the debate over the preferred site and design, whether names should be inscribed on the monument or not – also symbolises community spirit, participation, debate, and the evolution of a city. Perhaps one could also see this as a monument to a town coming of age.

Peter Arfanis, Archivist, Parramatta Council, Parramatta Heritage Centre, 2014

References

Parramatta Council Archives. Correspondence File PRS30/37

Parramatta Council Archives. Letter from Mayor PRS30/37/5

The Soldiers’ Memorial. (1920, September 4). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate p.1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103255446

The Soldiers’ Memorial. (1921, August 3). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate p.1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103816045

The Soldiers’ Memorial. (1921, December 3). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate p.6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103816417

The proposed Memorial. (1922, September 16). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate p.6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103306736

Parramatta’s Memorial. (1922, November 29). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate p.1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103317354

Parramatta’s War Memorial. (1923, January 24). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate p.1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article105919724

Soldiers’ Memorial. (1923, May 14). The Sydney Morning Herald p.8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16056406