On the 20th October 1914, the 1st Light Horse Regiment (AIF), as part of the 1st Light Horse Brigade, left Sydney with the first AIF convoy, on the Star of Victoria (A16). The Regiment numbered 24 Officers and 484 other ranks with 461 horses. Their destination was Egypt.

The Regiment disembarked at Alexandria on 8th December. It went into camp, first at Maadi and from January 1st 1915, Heliopolis, 6 miles out of Cairo.

The Light Horse were never expected to fight at Gallipoli. The country of the Gallipoli peninsular was totally unsuited to horses. The only reason they did was because the original landings failed, the fighting became a stalemate of trench warfare and the allies desperately needed reinforcements. The Light Horsemen were forced to leave their horses behind in Egypt and fight like infantry in the Gallipoli trenches.

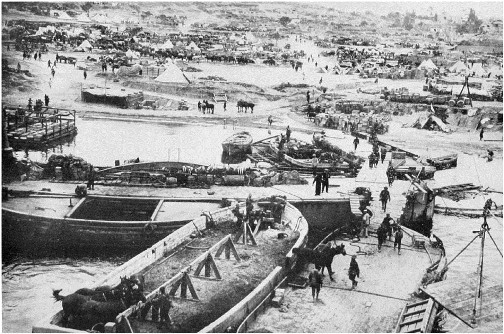

The 1st Light Horse landed at Gallipoli at 6am on 12th May 1915, 2,000 yards South of Fisherman’s Hut. They moved into the front line the following day at Pope’s Post. The enemy trenches were from 50 to 150 yards away. The Regiment rotated through periods in the front line and periods in reserve. Periodic Turkish attacks were repulsed, while life for the Light Horsemen was rarely free from the scourge of snipers and artillery barrages, causing regular casualties.

There was no freshwater available to the allied soldiers, so all freshwater had to be shipped to the peninsular from Malta and stored in big tanks at ANZAC Cove. Soldier’s placed on water fatigue duties had to leave the front line festooned with containers of all types, make their way to ANZAC Cove, fill up their containers with fresh water and return to the front line. This rapidly became the second most dangerous duty a soldier could be given (the most dangerous was to be ordered to leave the trenches and assault the Turkish lines), as it didn’t take the Turks long to work out the routes the water fatigue parties would have to take.

Rations in the trenches were almost exclusively bully beef and hard tack biscuits, while persistent flies swarmed in their millions. Sickness in the form of diarrhoea, dysentery, the flu and pneumonia were prevalent. Whenever possible, front line troops went down to ANZAC Cove to swim in the sea, a practice which became increasingly dangerous as the Turks began to shell the sea at times they expected allied soldiers would be out swimming.

To try and relieve the stalemate of trench fighting, the allied high command decided to make new landings at Suvla Bay, further North up the coast of the peninsular. To divert the Turks attention from these landings and draw away any reinforcements, the ANZACS were required to assault the Turkish positions at Lone Pine on the 6th August and at Chanuk Bair, the Chessboard and the Neck on the 7th. The New Zealanders were given the task of assaulting the high feature known as Chanuk Bair, and the 1st Light Horse at 4.30am on the 7th, in conjunction with Walker’s Post on the left and Quinn’s Post on the right, assaulting the strong Turkish trenches known as the “chessboard”, North of the Bloody Angle.

The 1st Light Horse’s assault was to be carried out by two Squadrons, about 200 men, under the command of Major JM Reid. No shots were to be fired and only bayonets used until the Turkish trenches were occupied. White patches were sewn onto the backs of the Light Horsemen’s shirts, so that no mistaken identities happened in the dark.

The storming party reached the third line of trenches and held on for two hours, but the enemy counter-attacked in great force and bombed the already thinned out Regiment back. The Regiment suffered heavy casualties, its largest in any one single action. The casualties included all the Officers in B Squadron, including Major Reid, whose body was never found. In total, the Regiment suffered 15 killed, 98 wounded, 34 missing (mostly killed), total 147 out of 200.

The courage of the wounded from all actions on that day on being carried to the beach was remarkable. Some 3,000 passed through the casualty clearing station that day, and boats in strings of four and five towed by small tugs, took the wounded off to empty transports where accommodation for them was hastily improvised. There was much suffering on the voyage to Alexandria, and many wounds were septic by the time they reached Cairo.

Summer and Spring moved into Autumn and Winter. The weather turned and became increasingly windy, wet and cold, the rain often becoming snow. The allies were very badly prepared to fight in the Winter, and with increasing storms the re-supply of those fighting on the peninsular became increasingly difficult. Eventually the decision was made to evacuate. Possibly the only successful part of the disastrous Gallipoli campaign was the evacuation. An elaborate deception plan was put into place to fool the Turks that the allied lines were still occupied, while the entire force was secretly and quietly withdrawn without incurring any casualties.

On 20th December 1915, the 1st Light Horse was evacuated, returned to Egypt and re-united with their horses. They then formed part of what became known as Harry Chauvel’s Desert Mounted Corps. They fought initially in defence of the Suez Canal from a Turkish advance, then across the Sinai, the defeat of the Turkish defensive line linking Gaza inland to Beersheba and finally, the victorious push into Palestine via Jerusalem and Damascus to the surrender of the Ottoman Empire on 30th October 1918.

![]()

Ian Hawthorn, Vice President, NSW Lancers Memorial Museum, 2020