The town of Parramatta may have been established on the 2 November 1788, but this proclamation was made on Phillip’s second visit to Parramatta, or Rose Hill as it was first named.

Earlier in the same year the first visit to the site was made by Phillip, Surgeon John White, Lieutenant Ball, Lieutenant George Johnston, Lieutenant Cresswell, the judge advocate, and nine soldiers and two seaman [see White’s entry for the 15th for core party details]. On the 22 April this group left Sydney Cove to continue their survey the limits of the harbour and to see if they could locate the large river they thought would run from the foot of the Blue Mountains.

John White, the First Fleet surgeon, who was also a keen naturalist, in 1790 published an account of this journey in a book with the rather long winded title, ‘Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, with sixty-five plates of non descript animals, birds, lizards,serpents, curious cones of trees and other natural productions [this is a link to the free online version]. What follows is his full account of their journey and the discovery of Parramatta.

22 April 1788: On the morning of this day the governor, accompanied by the same party, with the addition of Lieutenant Cresswell of the marines and six privates, landed at the head of the harbour,¹ with an intention of penetrating into the country westward, as far as seven days provisions would admit of; every individual carrying his own allowance of bread, beef, rum, and water.

The soldiers, beside their own provisions, carried a camp kettle and two tents, with their poles, &c. Thus equipped, with the additional weight of spare shoes, shirts, trowsers [sic.], together with a great coat, or Scotch plaid, for the purpose of sleeping in, as the nights were cold, we proceeded on our destination. We likewise took with us a small hand hatchet in order to mark the trees as we went on, those marks (called in America blazing) being the only guide to direct us in our return. The country was so rugged as to render it almost impossible to explore our way by the assistance of the compass.

In this manner we proceeded for a mile or two, through a part well covered with enormous trees, free from underwood. We then reached a thicket of brush-wood, which we found so impervious as to oblige us to return nearly to the place from whence we had set out in the morning. Here we encamped, near some stagnant water, for the night, during which it thundered, lightened, and rained. About eleven o’clock the governor was suddenly attacked with a most violent complaint in his side and loins, brought on by cold and fatigue, not having perfectly gotten the better of the last expedition.

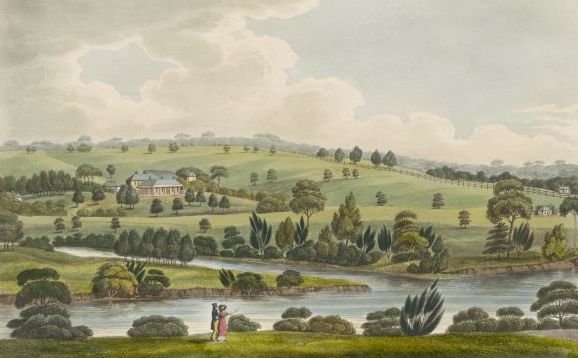

23 April 1788: The next morning being fine, his excellency, who was rather better, though still in pain, would not relinquish the object of his pursuit; and therefore we proceeded, and soon got round the wood or thicket which had harassed us so much the day before. After we had passed it, we fell in with an hitherto unperceived branch of Port Jackson harbour, along the bank of which the grass was tolerably rich and succulent, and in height nearly up to the middle, interspersed with a plant much resembling the indigo. We followed this branch westward for a few miles, until we came to a small fresh-water stream that emptied itself into it. Here we took up our quarters for the night, [the Lycett painting at the top of this post shows the entrance to this spot where the Parramatta River meets Clay Cliff Creek] as our halts were always regulated by fresh water, an essential point by no means to be dispensed with, and not very abundant or frequently to be met with, in this country. We made a kettle of excellent soup out of a white cockatoo and two crows, which I had shot, as we came along. The land all around us was similar to that which we had passed. At night we had thunder, lightning, and rain. The governor, though not free from pain, was rather recovering.

24 April 1788: As soon as the dew, which is remarkably heavy in this country, was off the ground, we proceeded to trace the river, or small arm of the sea. The banks of it were now pleasant, the trees immensely large, and at a considerable distance from each other; and the land around us flat and rather low, but well covered with the kind of grass just mentioned. Here the tide ceased to flow; and all further progress for boats was stopped by a flat space of large broad stones, over which a fresh-water stream ran. Just above this flat, close to the water-side, we discovered a quarry of slates, from which we expected to derive great advantage in respect to covering our houses, stores, &c., it being a material beyond conception difficult to be procured in this country; but on trial it was found of no use, as it proved to be of a crumbling and rotten nature.

On this fresh-water stream, as well as on the salt, we saw a great many ducks and teal, three of which we shot in the course of the day, besides two crows and some loraquets. About four in the afternoon, being near the head of the stream, and somewhat apprehensive of rain, we pitched our tents before the grass became wet, a circumstance which would have proved very uncomfortable during the night. Here we had our ducks picked, stuffed with some slices of salt beef, and roasted, and never did a repast seem more delicious; the salt beef, serving as a palatable substitute for the want of salt, gave it an agreeable

relish. The evening cleared up, and the night proved dry. During the latter, we heard a noise which not a little surprised us, on account of its resemblance to the human voice. What it proceeded from we could not discover, but I am of opinion that it was made by a bird, or some animal. The country round us was by no means so good, or the grass so abundant, as that which we had passed. The water, though neither clear nor in any great quantity, was neither of a bad quality nor ill-tasted.

25 April 1788: The next day, after having sowed some seeds, we pursued our route for three or four miles west, where we met with a mean hut belonging to some of the natives, but could not perceive the smallest trace of their having been there lately. Close to this hut we saw a kangaroo, which had come to drink at an adjacent pool of stagnated water, but we could not get within shot of it. A little farther on we fell in with three huts, as deserted as the former, and a swamp, not unlike the American rice grounds. Near this we, saw a tree in flames, without the least appearance of any natives; from which we suspected that it had been set on fire by lightning.

This circumstance was first suggested by Lieutenant Ball, who had remarked, as well as myself, that every part of the country, though the most inaccessible and rocky, appeared as if, at certain times of the year, it had been all on fire. Indeed in many parts we met with very large trees the trunks of which and branches were evidently rent, and demolished by lightning. Close by the burning tree we saw three kangaroos.

Though by this time very much fatigued, we proceeded about two miles farther on, in hopes of finding some good water, but without effect; and about half past four o’clock we took up our quarters near a stagnant pool. The ground was so very dry and parched that it was with some difficulty we could drive either our tent pegs or poles into it. The country about this spot was much clearer of underwood than that which we had passed during the day. The trees around us were immensely large, and the tops of them filled with loraquets and paroquets of exquisite beauty, which chattered to such a degree that we could scarcely hear each other speak. We fired several times at them, but the trees were so very high that we killed but few.

26 April 1788. We still directed our course westward, and passed another tree on fire, and others which were hollow and perforated by a small hole at the bottom, in which the natives seemed to have snared some animal. It was certainly done by the natives, as the trees where these holes or perforations were, had in general many knotches [sic.] cut for the purpose of getting to the top of them.

After this we crossed a water-course, which shews [sic.] that at some seasons the rain is very heavy here, notwithstanding that there was, at present, but little water in it. Beyond the chasm we came to a pleasant hill, the top of which was tolerably clear of trees and perfectly free from underwood. His excellency gave it the name of Belle Veüe [now called Prospect Hill].

From the top of this hill we saw a chain of hills or mountains, which appeared to be thirty or forty miles distant, running in a north and south direction. The northernmost being conspicuously higher than any of the rest, the governor called it Richmond Hill; the next, or those in the centre, Lansdown Hills; and those to the southward, which are by much the lowest, Carmarthen Hills.

In a valley below Belle Veüe we saw a fire, and by it found some chewed root of a saline taste, which shewed that the natives had recently been there. The country hereabout was pleasant to the eye, well wooded, and covered with long sour grass, growing in tufts. At the bottom of this valley, or flat, we crossed another water-course and ascended a hill, where the

wood was so very thick as to obstruct our view.

Here, finding our provisions to run short, our return was concluded on, though with great reluctance, as it was our wish, and had been our determination, to reach the hills before us if it had been possible. In our way back, which we easily discovered by the marks made in the trees, we saw a hollow tree on fire, the smoke issuing out of the top part as through a chimney. On coming near, and minutely examining it, we found that it had been set on fire by the natives; for there was some dry grass lighted and put into the hole wherein we had supposed they used to snare or take the animal before alluded to. In the evening, where we pitched our tents we shot two crows and some loraquets, for supper. The night was fine and clear, during which we often heard, as before, a sound like the human voice, and, from its continuance on one spot, we concluded it to proceed from a bird perched on some of the trees near us.

27 April 1788: We now found ourselves obliged to make a forced march back, as our provisions were quite exhausted, a circumstance rather alarming in case of losing our way, which, however, we met with no difficulty in discovering by the marked trees. By our calculation we had penetrated into the country, to the westward, not less than thirty-two or thirty-three miles. This day we saw the dung of an animal as large as that of a horse, but it was more like the excrement of a hog, intermixed with grass.

When we got as far back as the arm or branch of the sea which forms the upper part of Port Jackson harbour, we saw many ducks, but could not get within shot of any of them. It was now growing late, and the governor being apprehensive that the boats, which he had ordered to attend daily, might be, for that day, returning before we could reach them, he sent Lieutenants Johnston and Cresswell, with a marine, ahead, in order to secure such provisions as might have been sent up, and to give directions for the boats to come for us the next morning, as it then appeared very unlikely that all the party, who were, without exception, much fatigued, could be there soon enough to save the tide down.

Those gentlemen accordingly went forward, and were so fortunate as to be just in time; and they returned to us with a seasonable supply of bread, beef, rum, and wine. As soon as they had joined us, we encamped for the night, on a spot about the distance of a mile from the place where the boats were to take us up in the morning.

28 April 1788: His excellency was again indisposed, occasioned by a return of his complaint, which had been brought on by a fall into a hollow place in the ground that, being concealed by the long grass, he was unable to discern. We passed the next day in examining different inlets in the upper part of the harbour. We saw there some of the natives, who, in their canoes, came along-side of the boat, to receive some trifles which the governor held out to them. In the evening we returned to Sydney Cove.

Neera Sahni, Research Services Leader, Parramatta Heritage Centre, City of Parramatta, 2015

References:

Surgeon John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, with sixty-five plates of non descript animals, birds, lizards,serpents, curious cones of trees and other natural productions, 1790