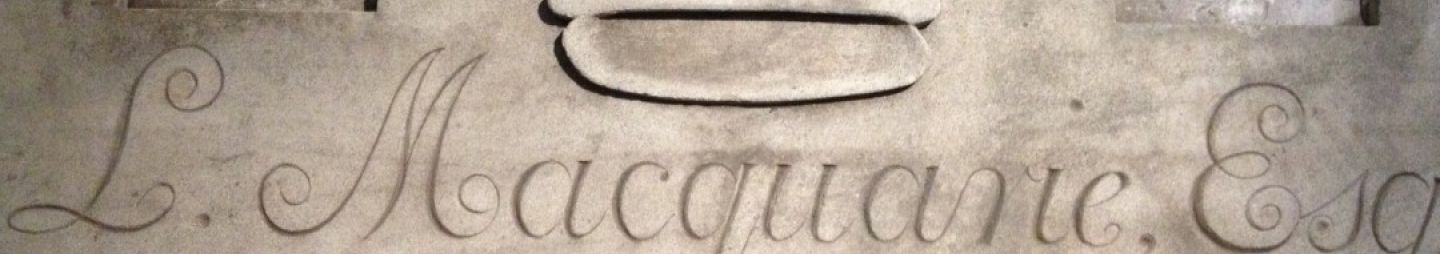

This commemorative stone was originally laid in a building called the Macquarie Barracks in Parramatta. This building, also known as the Convict Barracks, was built in 1820 and demolished in the 1930s. it was a Georgian brick building constructed during Macquarie’s governorship (1810-1821) which saw Parramatta witness its first wave of substantial urban planning. Macquarie had great plans for the colony and “by the end of 1821, Macquarie had rebuilt Sydney’s public buildings in a manner congruent with his image of Empire.”[1] Similar commemorative stones can be seen in other buildings commissioned by Governor Macquarie, including the Windsor Courthouse and the Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney.

The building was on the north side of Macquarie Street, near Barrack Lane and Arthur Philip High School. Various accounts list Francis Lawless, a foreman bricklayer for the Government gangs, as responsible for the construction of the Barracks.[2] According to Morton Herman in his book, The Early Australian Architects and their work, Parramatta Barracks were a good example of a simple Georgian building using quality materials and proportions to produce an attractive building. “The barracks were large, having a main block on Macquarie Street and two very curiously fenestrated blocks, each 208 feet long, flanking the courtyard which sloped down to the north towards the river. All three blocks showed the small break forward at the centre of the building, with the triangle of the roof gable above expressed as the centre point of the façade.”[3]

Under this roof gable is where the commemorative stone was laid. Herman goes on to say that this technique was also used on the first substantial dwelling built Australia, Government House in Sydney (now demolished), as it was a favoured device with the Colonial designers.[4]

Plans for the convict barracks in Parramatta.

Source: The Early Australian Architects and their work by Morton Herman, 1970.

During the construction of the Macquarie (Convict) Barracks, the convicts housed there were assigned to day labour so were free to come and go but returned for lodging each night. According to a report in The Advertiser, convicts from the Barracks also worked on the construction of Lennox Bridge and were marched to work each day from the Barracks.[5]

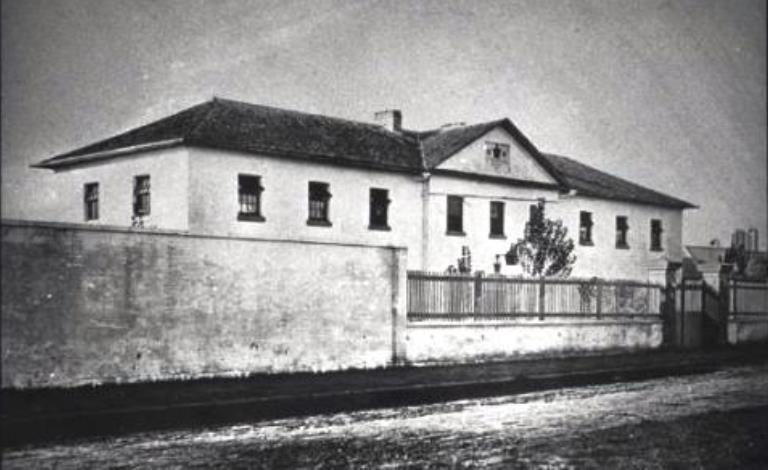

Local Studies Collection LSOP 168. Macquarie Barracks, also known as the Convict Barracks and later the Macquarie Street Asylum in Parramatta, circa 1900

The building had an interesting history over its 115 years of existence. According to NSW State Records, the Barracks was first listed as a Government Institution in June 1884.

The premises were originally built as stables and barracks for convicts, before being converted into a Military Hospital in 1843. After the military hospital closed in 1851, the premises were utilised by The Erysipelas Hospital. Although functioning as an asylum for infirm and destitute men from 1884, wards for infectious conditions were still maintained and used for cases refused admission to Sydney Hospital, the Macquarie Street Asylum reputed to be ‘one hospital whose doors are open to all kinds of disease.’ The Government Asylums generally included medical wards, and Macquarie Street became the centre for treatment of serious eye conditions, with 342 ophthalmic cases treated at Macquarie Street in 1893. After administrative responsibility for Government Asylums transferred from the Department of Charitable Institutions to Public Health in 1913, Macquarie Street asylum became known as the State Hospital and Asylum for the Blind and Men of defective Sight and Senility, Macquarie Street, Parramatta.

During 1926, admissions to the Hospital numbered 703, with 173 remaining resident at the end of the year. Residents of Government Asylums who were able to work were expected to contribute towards a measure of self-sufficiency, at Macquarie Street residents made clothing and bedding, carried out repairs to the building, and assisted in the Bakery which supplied bread and pastries to all the State hospitals.[6]

The Macquarie Street Asylum had a terrible reputation, as evidenced by an article written by an ex-patient in 1881. Written in the Australian Magazine under the title, The Interior of a Government Asylum, the author wrote:

I found the Asylum in Macquarie Street, Parramatta, and to which I was transferred, peopled by some of the most extraordinary concentrations of suffering and indigent humanity possible to conceive. They then numbered some three hundred and twenty souls (320). Men of every nation and calling, of creeds indescribable. The majority well nigh worn out already in the world’s service, many of them originally deportes from the old country, and all, more or less, apparently suffering from almost every description of ailment known to medical science, and, verily, if the highways and hedges of NSW had been searched for recruits, a more deplorable assemblage of bodily wretchedness could not have been gathered together into one refuge…..In short, the Macquarie Street Asylum seems to be a dernier resort for victims of and disease disagreeable to the management of other public institutions.

There is a large and central building, facing the street, and at the rear all the attendant dormitories, lavatories, wash-houses, kitchens, etc necessary to the completion of a well-ordered establishment. A large open shed from the northern boundary, and between it and the main building is a well-kept recreation yard, a portion of it laid down in grass, and the other three sides nicely ornamented with flower beds. Close adjoining, but separate entirely from the yard and dormitories are a couple of brick cottages, which are left apart for leprosy and other fever cases-or men suffering dangerously infectious diseases.

I am well aware that the usual purport or intention of papers such as this, is to show up any faults or malpractices on the part of officials connected with the institution under notice; but even did any such exist in this particular instance, I would not consider it my duty to refer to them. I don’t intend to insinuate that the management of this Asylum is perfection itself; but this I can say, and I have had much opportunity of visiting like charities in other parts of the world and colonies, in brighter days, that the general direction of the Macquarie Street asylum reflects infinite credit upon the matron and those placed under her control……Sooner or later the whole question as to the management of these charitable institutions must become a matter for strict legislative inquiry, from the increased accommodation required year after year.[7]

The final stage of the building saw it house elderly, destitute men. NSW State records state that in January 1935, the premises were found to be in an unsatisfactory condition and not fit for renovation so patients were transferred to Lidcombe State Hospital. In July/August that year, the building was demolished.[8] In 1935, an article in The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, described the process of moving the patients from Parramatta to Lidcombe Old Men’s Home.

“…the first section to be removed being that attached to the bakery. Thereafter the trek will be a gradual one, extending over three or four weeks. It is anticipated that the Macquarie Street buildings will be evacuated early next month. Officials connected with the homes state that the bakers are being removed first so that they will be ready to provide the increased supply of bread that will be necessary at Lidcombe….Following the transfer of its inmates, the Macquarie Street home will probably be taken over by the Department of Education, which may demolish the old structure and erect a school on the site. One thing is certain – the old home will not be allowed to remain long in idleness. We may expect some developments in that quarter in the near future.”[9]

The commemorative stone is the only remnant of this historic building commissioned by Governor Macquarie, and home to many over the years. It is unknown where the stone went after the building was demolished in 1935 but it appeared again in the new David Jones building when it was built in 1961. The stone was placed in a wall facing Parramatta River, by The Royal Australian Historical Society.

It seems the commemorative stone was removed from the David Jones building and temporarily stored in the Council depot before it moved to the permanent exhibition space at the Parramatta Heritage Centre.

![]() Alison Lykissas, Cultural Collections Officer, Parramatta Heritage Centre, July 2014 (updated 2018)

Alison Lykissas, Cultural Collections Officer, Parramatta Heritage Centre, July 2014 (updated 2018)

References:

- Herman, M, The Early Australian Architects and their work, Angus and Robertson Sydney 1970

- Siman Kevicius, Macquarie’s Kingdom, Good Walking Books, Marrickville 2004

- Plaque is a reminder of Convict Barracks, The Advertiser, 15 November 1973

- NSW State Records http://investigator.records.nsw.gov.au/entity.aspx?path=%5Cagency%5C1998, viewed August 2014

- The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, January 10, 1935 http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/105088348?searchTerm=Macquarie&searchLimits=dateFrom=1935-01-10|||dateTo=1935-01-10, viewed August 2014

- The Interior of a Government Asylum, Australian Magazine, Volume 5, No 4, January 1881, page 416-417

- Rivett, C, Old Parramatta: since 1788 and all that, Parramatta City Council Centenary Celebrations

Endnotes

[1] Simankevicius, A Macquarie’s Kingdom, Marrickville Walking Books, 2004 page 86

[2] Herman, Morton The Early Australian Architects and their work, Angus and Robertson Sydney 1970, page 100-101

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] Plaque is reminder of Convict Barracks, The Advertiser 1973

[6] State Records NSW, History of the Macquarie Street Asylum, viewed August 2014 http://investigator.records.nsw.gov.au/entity.aspx?path=%5Cagency%5C1998

[7] The Interior of a Government Asylum, Australian Magazine, Volume 5, No 4, January 1881, page 416-417

[8] NSW State Records, History of the Macquarie Street Asylum, viewed August 2014 http://investigator.records.nsw.gov.au/entity.aspx?path=%5Cagency%5C1998

[9] The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, January 10, 1935, page 21.