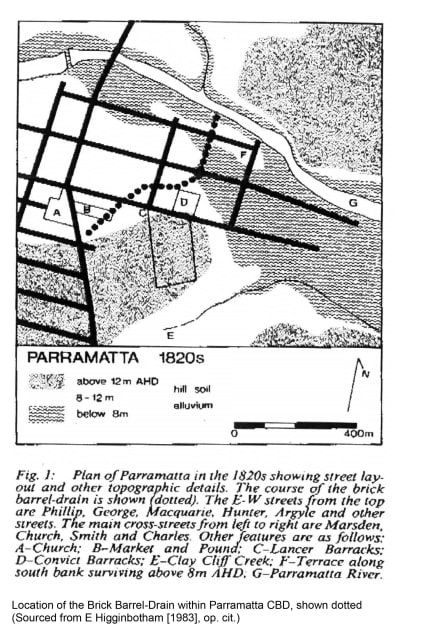

The area between the Parramatta River foreshore and the railway line next to Parramatta Square was originally a shallow valley of numerous low mounds and depressions all of which were imperfectly drained into swampy land to the north-east. To complicate matters there was a low ridge next to the railway station running north-east from the station which created a block to the natural drainage of the area leaving the place a swampy quagmire in heavy rains. In addition the accumulation of water in hollows around the rear of where the Town Hall created a series of ponds one of which was directly under the site of the old public library. The early drainage for this area can be seen marked as a series of dots in the diagram below. The area west of Church Street appears to have been drained by a channel between Marsden and O’Connell Streets into the Parramatta River.

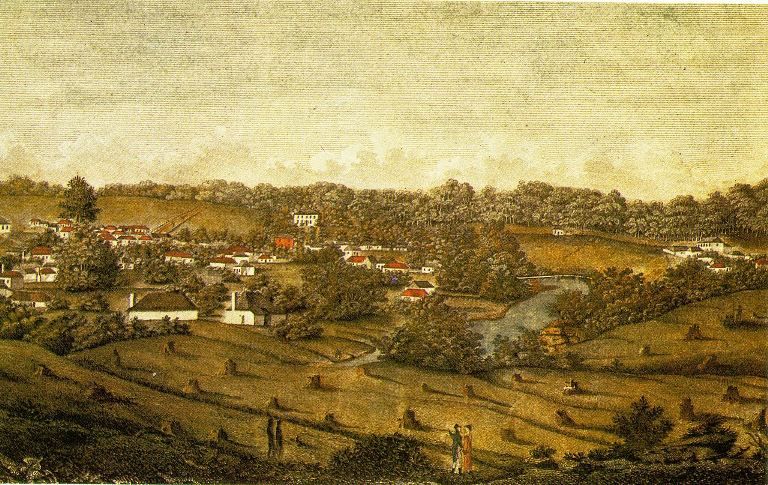

After European settlement in 1788 the rapid expansion of Parramatta township led to an increase in the associate problems caused by water accumulating where new homes, and roads were being built. While water (and waste) was initially washed by rainwater along the natural contours of the landscape into the creeks into the river or swamps the new layout of the buildings and streets started to alter the flow of rainwater.

The first drains obviously sought to make use of the systems created by nature and open ditches were dug to channel the flow. But as new streets were built for efficient movement of carts, horses and people new bridges were built, hollows were filled in, and hills cut into and removed. As a result covered drains were needed to flow beneath roads and new drains were dug to follow the contours of the township rather than nature.

Over time the natural drainage system of other areas around the township were progressively covered up. One example of this was Clay Cliff Creek which was once a freshwater stream which started in the Merrylands district and flowed by Experiment and Elizabeth farms. It’s meandering course near these heritage sites is now a concrete lined storm-water drain while its course east of James Ruse Drive was straightened in the early 1900s to allow for road work extensions.

These changes were not unique to Parramatta as they were reflected more broadly across Sydney. In fact the control of Sydney’s water system since European settlement can be broken down into four distinct approaches. The first phase from 1788-1840 was the development pipes and drains to manage the town’s water supply and sanitation needs. This work was done under direction from the Governor of the Colony.

The second phase from 1840 -1880 saw responsibility move to local government and then the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales. The third phase started in 1888 when a statutory board was created to oversee the management of the water and sewage systems and up until 1924 major capital works were the responsibility of the Department of Public Works. And the final era, still in place today, began in the 1970s with the major reforms to the statutory authority.

In Parramatta the early open cut drains were replaced with “brick barrel” drains common throughout much of the British Empire. These large underground drains were made from bricks and cement and carried excess water to the Parramatta River or areas which would more readily dry out after a heavy downpour. A portion of one of these made between 1822 and 1827 was uncovered in 1980 and can be seen on display on Philip Street at the rear of 126-138 George Street. This cylindrical brickwork drain has two courses of 200 millimetre brick and an internal diameter of 1200 to 1300 millimetres.

Once a major drainage system for early Parramatta it joined up with a number of smaller drains, including the sandstone box drain uncovered during the 1989 excavation of the stables of a house at 79 George Street. Originally built by Nathaniel Payten the sandstone box drain started close to Argyle Street and Church Street and ran past the old market and pound, and old Council Chambers in Parramatta Square. it then ran across the property once owned by Harriet Holland and Dr. Woolnough before crossing Macquarie Street.

The New South Wales Heritage Office archaeological assessment of this site also notes on the site that the northern end of this drain reverts into a brick and cement rendered drain near the rear of the Parramatta Town Hall.

In 1852 the British ‘General Board of Health’ advocated the use of smaller pipes instead of the large brick and stone drains then in use. This in turn seems to have led to the adoption of smaller earthenware pipes in public drains and sewers across the colonies as well. It was also around this time that an outbreak of cholera connected to a well on Broad Street, London, formed the basis for a remarkable investigation which finally linked disease to the polluting of water. This in turn led to a complete reappraisal of water and sewage systems and in particular the leaching of pollutants from mortar joints in the old “brick barrel” drains.

This led to the next phase of development which was the introduction of smaller locally made earthenware pipes and the identification of the need to stop polluting the Parramatta River. By 1889 there were many concerns about public health as the rock and stones trapped all manner of putrid matter which refused to be flushed out even at low tide. At a special meeting of the Council in April 1889 it was decided to clean up the river bed, which locals felt was the cause of all manner of diseases including typhoid fever.

While some of this was caused by the disposal of waste from the Hospital, Asylum and Gaol located upriver from the weir, there was enough of a problem downstream to warrant a call for a complete overhaul of the sewerage system. In 1892, after the Hunt’s Creek Dam water supply was assured, Parramatta Council set about installing its own sewerage scheme in conjunction with the Public Works Committee. Initial proposals focussed on draining directly into the swampy land at the end of Grand Avenue but finally in 1897 it was decided to erect a treatment station at the junction of Clay Cliff Creek and the Parramatta River. The costs for this project also included the 14,864 pounds already spent on constructing storm-water channels to relieve the nuisance of slop water being discharged into creeks. The project also saw the length of sewers increased from 15 miles 20 chains to 20 miles and 20 chains.

The work was completed in February 1910 at a cost of £66,000. However the scheme was absorbed by a new plan where all sewage from the district was pumped directly to an ocean outfall system at Manly. The redundant septic tanks were abandoned and eventually used for mushroom growing by the Parramatta Mushroom Company. A boat builder was located nearby whose gas turbine motor was powered by methane gas from the sewerage works.

![]() Geoff Barker, Research and Collection Services Coordinator, Parramatta Council Heritage Centre, 2015

Geoff Barker, Research and Collection Services Coordinator, Parramatta Council Heritage Centre, 2015

References

Edward Higginbotham & Associates Pty Ltd, http://www.higginbotham.com.au/majorexcavations.html

J J Cosgrove, Histoy of Sanitation, 1909

The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Wednesday 20 September 1905, page 4

Donald Hector, Sydney’s Water Sewerage and Draining System, Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 144, p.3-5

John McClymont, Clay Cliff Creek, unpublished manuscript donated to the Parramatta Heritage Centre by Beverly McClymont, 2014

Convict Drain, 72, 74, 119 and 119A Macquarie Street, New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2240103