The front gardens in the eastern section of the Cumberland Health precinct may look unassuming but the design and plantings reflect a long and interesting history. Before its current incarnation as part of the Cumberland Health campus, this precinct bore witness to early colonial land grants and a succession of institutions devoted to caring for the less fortunate.

The first European owner, Charles Smith, sold his farming land to the Reverend Samuel Marsden who built the government water mill on the near the site of the Roman Catholic Orphan School. A mill race was dug to bring water from the river to the mill’s pond and it traversed several precincts within the Cumberland Hospital site. The original alignment ran along the western border of the gardens however this was diverted to the area north of the gardens in the 1820s. Of additional significance is that this mill race was potentially incorporated into a drainage system associated with later institutions, such as the Female Factory and the Parramatta Hospital for the Insane.[1] On the eastern side of the gardens is Fleet Street and this was named after the mill race or ‘fleet’ for the mill.[2]

This garden precinct has remained the main entry point, for successive institutions built on the Cumberland precinct, from the mid-1800s to the present day. The landscaping of the site was originally intended to be read as a whole and it was designed to maximise views of the Parramatta River and surrounding farmland. By the 1890s, the basic framework of the gardens had been established. According to a National Trust of Australia report,

“…the pathway system, garden areas and shrubberies throughout the hospital were established with orchards, vegetable gardens and vineyard on the periphery. Trees were supplied by the Botanic Gardens and plants listed as being supplied in the 1870s such as the Schinus terebinthifolia and Plane Trees still survive on the site today.”[3]

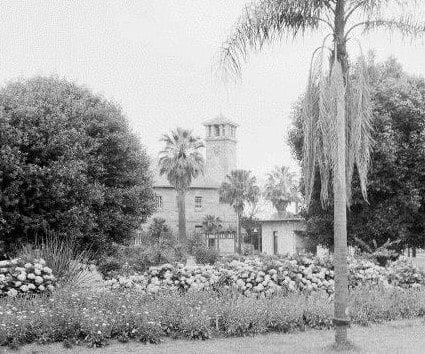

Front gardens along Greenup Drive by E.W.Searle, ca 1935 Source: National Library Australia (vn4654261-v)

The Female Factory was the first institution to occupy the site between Fleet St and the Parramatta River from 1818 to 1848. It was designed by Francis Greenway as a series of sandstone buildings to house female convicts. In the late 1840s the Colonial Government made the decision to turn the Parramatta Female Factory into the Asylum for Invalid and Lunatic Convicts (1848 – 1849) after the nearby Tarban Creek facility (in Gladesville) had reached capacity. For the duration of the Asylum, the administrative offices, residences for officials and stores were all clustered near the Fleet Street entrance gates.[4]

In 1852 Dr Richard Greenup was appointed as the first Medical Superintendent. He believed that engaging patients in meaningful work was beneficial and during the day patients were involved in tasks such as cleaning, sewing, laundry, along with maintaining the buildings and gardens. Unfortunately, his humanitarian approach to mental health care came to an abrupt end when he was killed by one of his patients. During his time at the Asylum, Greenup was involved in discussions about encouraging patients back into the community. Unfortunately his murder put a halt to this thinking and the institutionalisation of mental health patients continued apace. Greenup Drive on the western side of the gardens is named after him.[5]

In 1876, Dr Frederick North Manning was appointed the first Inspector General of the Insane NSW. Following a study tour of institutions in the USA, England, France and Germany, Manning introduced the Lunacy Act 1878. This resulted in major improvements to mental health care in the colony and the precinct was renamed Parramatta Hospital for the Insane. This period saw major modifications with changes to the layout of the site, additions and replacement of older buildings. Manning advocated for mental health to be treated as an illness rather than a crime. He encouraged public visitation to the hospitals in an effort to break down the stigma. At Parramatta, one of the primary aims of the improvements was to encourage patients to take part in healthy outdoor activities,

“A large sports oval and cricket ground was created in 1879 with an open air shelter pavilion added the following year to encourage healthy participation in physical activities. This amenity, along with a bowling green in front of Ward 1, became important social venues for activities between patients and staff and visiting teams from other institutions. With landscaped park-like grounds, an aviary, fountains, terraced riverbanks, formal gardens and new buildings, some re-using the stone from earlier structures, the Asylum environment was considerably enhanced. The ha-ha kept patients within the grounds, but afforded views of the landscape and a sense of freedom. Windows, although barred, were given decorative treatment, rather than prison-like bars.” [6]

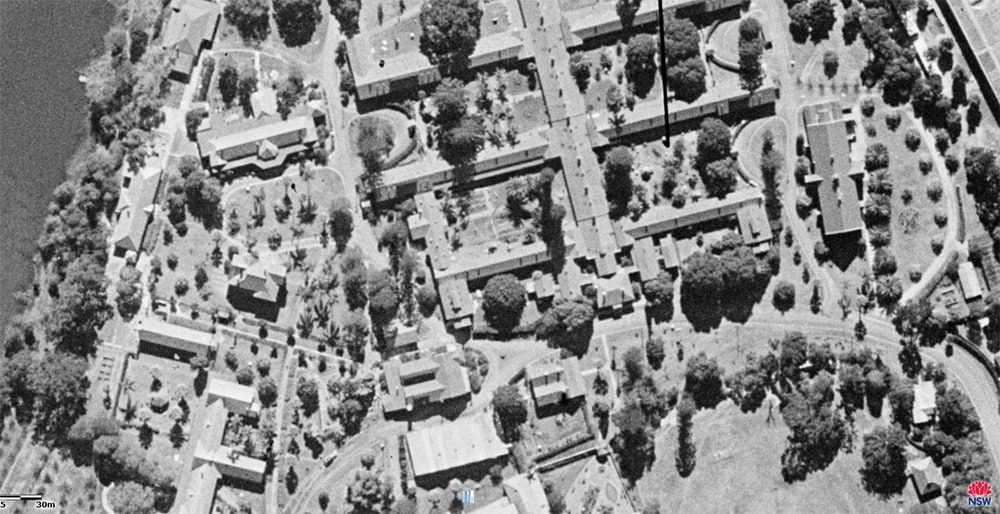

Aerial View of Northern Gardens, Cumberland Hospital, Parramatta, 1943, State Archives Six Maps Project

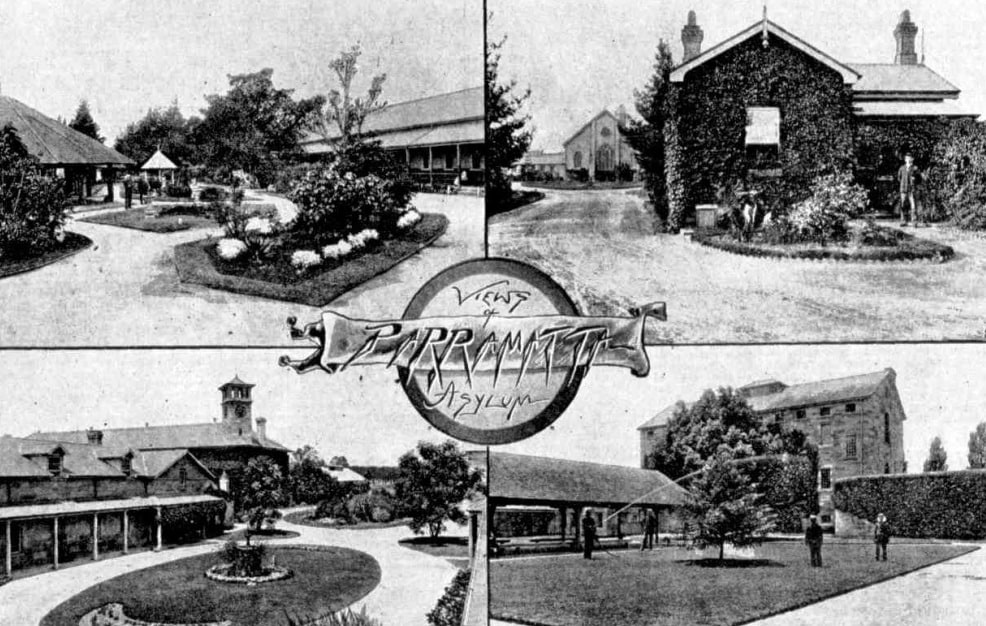

Reporting in the Australian Town and Country Journal of 1885, the Parramatta Asylum is described as being about a mile above Lennox Bridge and covering about 120 acres on both sides of the Parramatta River. Within that land parcel, 30 acres was devoted to a farm growing fruit and vegetables, 60 acres as pasture for the animals and the remainder comprised buildings, private enclosures and recreation grounds. The main entry through the Fleet Street gates is described as follows,

“What strikes the visitor on entering the main gates is the exquisitely clean and neat appearance of the buildings and their surroundings. Closely shaven lawns, well-rolled gravel paths, and flower-beds bright with coloured walls covered with ivy and the climbing ficus, and in some cases the gorgeously-tinted bougainvillea, all be token a great amount of case on the part of the gardener and his assistants, and show that amongst other curative, or palliative measures used, that of beautiful surroundings holds no small place in the system adopted. Ornamental fountains and statuary, some the work of attendants, are also frequently met with: one of the former especially worth attention having been constructed by an attendant out of clinkers from the steam boiler furnaces.”[7]

Gardens inside the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum. Source: Australian Town and Country Journal, 12 Jan 1895, page 26

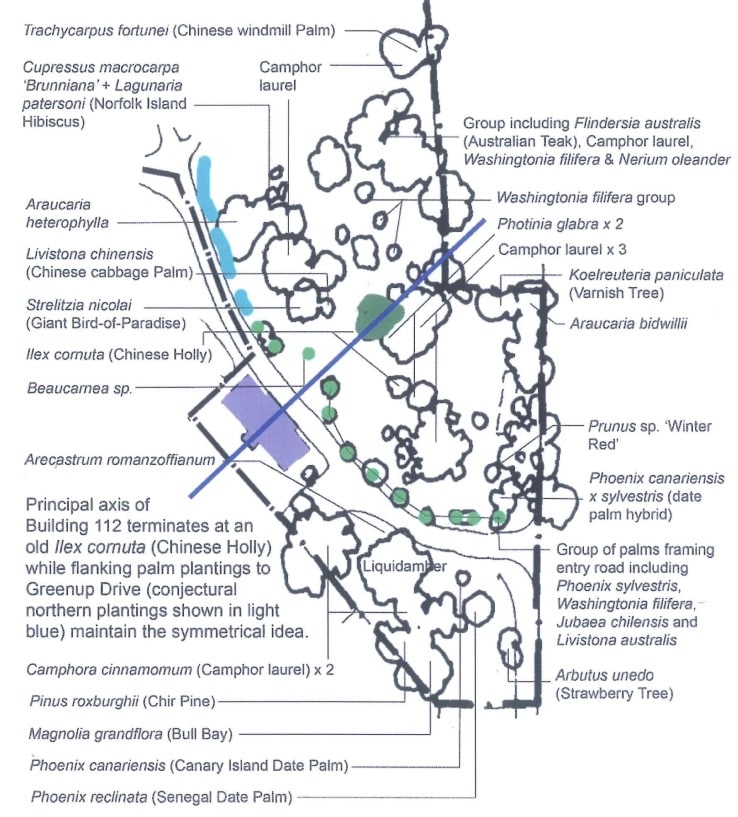

Changes to the site continued in the early 1900s, and are still evident today. Between 1901 and 1960, the site was known as the Parramatta Psychiatric Hospital. The Government Architect, Walter Liberty Vernon was responsible for designing a series of buildings on the site that interacted and celebrated the importance of the garden setting in mental health care. His planning was informed by the Garden City Movement and there remains a significant collection of plants which have been attributed to the involvement of Joseph Henry Maiden, Director of the Royal Botanical Gardens between 1896 and 1924. During this time, the Royal Botanic Gardens supplied many government institutions with plant materials and advice.[8] The importance of the garden setting can still be seen today in the nomenclature of the buildings throughout the whole site using non-scientific botanical names, such as Rose, Figtree, Wisteria, Willow, Acacia, Banksia, Jarrah and Pine.

“Evidence of the major 1900s hospital redevelopment phase includes the substantial group of plantings that dominate the precinct and forms a major part of the plant collection within the campus notable for its extant and botanical diversity. It includes six species that represent an impressive campus-wide collection of Australian rainforest species. A species of the Mexican/Southern USA genus Beaucarnea (syn.Nolina) is rare in cultivation and certainly at this age. The rare Beaucarnea and some of the Australian rainforest species were probably used by the Botanic Gardens as an exercise in testing the cultural application of species hitherto little used horticulturally in Australia.” [9]

The Department of Environment and Heritage describes the site as housing a rare and substantially intact public landscape designed between 1860 and 1920. Included within the grounds are rainforest species, both native and exotic, conifers and palms. Of particular note are five large specimens of Canary Island pine trees (Pinus Canariensis). Scattered throughout the grounds are shrubs and climbers that represent 1800s and early 1900s garden design.[10]

Survey of key plantings by Geoffrey Britton (Source: Conservation Management Plan Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, 2010, page 294. Report by Perumal Murphy Alessi and Higginbotham, Britton, Kass)

As Medical Superintendent during the period 1900 to 1921, Dr William Cotter Williamson was another strong advocate for the inclusion of landscaped grounds within and around the institution, believing they were an essential part of patient care and therapy. In 1907 at a Council meeting, Dr Williamson requested permission to plant a row of plane trees in the gardens along the Fleet Street. His request was granted as it was recognised that Dr Williamson had contributed greatly to the hospital and its grounds.

“His Worship stated that Dr Williamson had done much and was doing much, not only to improve the grounds (and to make them a place well worth visiting for the sake of their own attractiveness), but also to improve that part of Parramatta North in the vicinity of the Hospital.” [11]

To undertake the improvements, Dr Williamson utilised patient labour for both practical and therapeutic reasons. A newspaper article in 1917 reported that:

“…patients are privileged to work but are never forced to do it. There are recreation grounds where cricket and tennis can be played. Outdoor exercise is necessary for the well-being of some of the patients, and these often find an outlet for their energies in helping with gardening work or other undertakings in the hospital.” [12]

Patient labour is also evident in the low stone wall between the gardens and Fleet Street. It was built during the depression (1929 and 1932). Extending along both sides of the entrance, it was constructed by groups of patients using stone rubble obtained from the former Hospital quarry across the road. The walls follow the alignment of Fleet Street and are interspersed with small capped piers. Much of the wall along the north and south points of entry from Fleet Street are overgrown with garden. The north part of the stone wall follows the contours of the front garden area to the hospital.

Of note inside the front gardens are two brick buildings and a water fountain. Upon entering the Fleet Street garden precinct, the first building on Greenup Drive is a toilet block. It is a small brick building with a gabled roof of terracotta tiles. It was constructed in 1955 and is surrounded by grass apart from a large tree immediately adjacent and several palm trees close by.

The next building along Greenup Drive houses a Mental Health Services Centre, the former Administration block for the Parramatta Hospital for the Insane. Designed as part of the Walter Liberty Vernon master plan, it was built in 1909. Located on the western side of Greenup Drive the building is the most prominent within the front garden precinct. It is a single storey brick building with sandstone details and a hipped slate roof. The front of the building has a recessed front porch supported by round sandstone columns.

GPMS Mental Health Services Unit (former Administration block Parramatta Hospital for the Insane). Source: Parramatta Council Heritage Centre, Alison Lykissas, August 2015

The old entrance gates of the Female Factory, which were then part of the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, were demolished to make way for the building. The building’s alignment is with the original central axis of the Female Factory and it used to have direct visual and axial connection to the Parramatta River. Visiting today one can see the surviving portions of the Female Factory buildings flanking each side. Facing the gardens and directly in front of the building is a large Chinese Holly (Ilex cornuta) tree which continues the central axis of the layout (which can be seen in the preceeding planting layout by Geoffrey Britton).[13]

Fountain at entrance to Parramatta Lunatic Asylum. (Source: Parramatta Council Heritage Centre – Local Studies P00124)

To the north-west of the administration building is a water fountain with three tiers, which is thought to have been built by asylum patients. The exact date of construction is unknown however it is thought to be prior to 1909 when the Administration block was built, and the fountain was moved north to make way for the construction.[14] Water fountains, and later drinking fountains, were an integral part of the overall garden design within the precinct. The image below shows the original location of the water fountain at the entrance gates to the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum. The following photo, in its new location, shows it overgrown and surrounded by lawn.

Rusticated fountain, Greenup Drive (Source: Parramatta Council Heritage Centre, Maribel Rosales, July 2015)

From the 1960s to present day, the site has been under the management of Cumberland Hospital. Very little additional changes have been made. However, given the extensive European activity on this site since the early 1800s, several archaeology and landscape assessment reports have been conducted. In addition to the above ground sites mentioned in this precinct, Archaeologist Edward Higginbotham has detailed the significant below ground archaeology of the historic sites that were located within the garden precinct, including,

“…the sites of a former gatehouse and a residence …located on the Fleet Street frontage, north of the main entrance. The site of a house and outbuildings is located within the front gardens, opposite Albert Street and on the north side of the present main entrance. It was built prior to 1876. By the early 20th century, the house seems to have been replaced by a gatehouse, now also demolished.”[15]

As well as containing several important botanical species, it is additionally important to consider the front garden precinct as part of the overall landscape for the Cumberland Precinct.

“The extent, layout (evidence of spatial planning), integrity, plant diversity and maturity of the study site landscape constitutes a major component of the setting of the place. Along with the traditional views of the river corridor and surrounding areas such as Parramatta Park and Wisteria Gardens this setting should be conserved.” [16]

![]() Alison Lykissas, Cultural Collections Officer, Parramatta City Council Heritage Centre, 2015

Alison Lykissas, Cultural Collections Officer, Parramatta City Council Heritage Centre, 2015

Footnotes:

[1] Higginbotham, E 2010, page 80

[2] Higginbotham, E 1992, page 29

[3] National Trust, 2014, page 6

[4] Higginbotham, E 2010, page 34

[5] Edwards, G 1972, page 6

[6] Betteridge, M 2014, page 54

[7] Australian Town and Country Journal, 1885, page 26

[8] Higginbotham, E 2010, page 335

[9] Ibid, page 340

[10] NSW Department of Heritage, 2015

[11] The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 2 Feb 1907, page 6

[12] Jago, W The Wingham Chronicle and Manning River Observer, 13 Jan 1917, page 2

[13] Higginbotham, E 1992, page 279 – 281

[14] Higginbotham, E 2010, page 280

[15] Higginbotham, E op cit, page 22

[16] Betteridge, C 2014, page 30

References:

Australian Town and Country Journal, 12 January 1885, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/71224464?searchTerm=asylum%20fountain%20parramatta&searchLimits,

Betteridge, M Baseline Assessment of Social Significance of Cumberland East Precinct and Sports and Leisure Precinct and Interpretive Framework, 21 October 2014 (Report for Urban Growth) http://urbangrowthnsw.com.au/downloads/file/ourprojects/8PNURSocialSignificanceFINAL.pdf

Betteridge, C Parramatta North Urban Renewal Cultural Landscape Heritage Assessment: A report on significant views and other cultural landscape issues, 29 Oct 2014 (Report for Urban Growth) https://majorprojects.affinitylive.com/public/c92542a54db7980924311f88b99c7929/3.6%20PNUR%20Landscape%20Heritage%20FINAL.pdf

Casey, M & Lowe, Baseline Archaeological Assessment and Statement of Heritage Impact Historical Archaeology, October 2014 (Report for Urban Growth) http://urbangrowthnsw.com.au/downloads/file/ourprojects/6PNUREuropeanArchaeologyFINAL.pdf

Empire, 17 August 1871, page3 http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/60875191?searchTerm=asylum%20fountain%20parramatta&searchLimits=

Edwards, G Factory to Asylum 1972 Unknown publisher?

Jago, W The Wingham Chronicle and Manning River Observer NSW, 13 Jan 1917, page 2 http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/166785794?searchTerm=parramatta%20hospital%20for%20the%20insane%20gardens&searchLimits

Higginbotham, E Cumberland Hospital, Fleet Street, North Parramatta, NSW – Archaeological Management Plan (Historical Sites) for Conservation Management Plan (Report for Perumal

Murphy Alessi and Sydney West Area Health Service, NSW Health). March 2010

Higginbotham, E Conservation Plan for the Cumberland Hospital Heritage Precinct, Fleet Street, Parramatta, NSW 1992 http://nswaol.library.usyd.edu.au/view?docId=pdfs/13170_ID_Higginbotham1992CumberlandHospitalHrtgPrecinctConservPlan.pdf;query=;brand=default

National Trust of Australia, 2014 http://wixxyleaks.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/National-Trust-Submission.pdf

NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, 24 July 2015 http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5051959

The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 2 Feb 1907, page 6 http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/86161816