The passing of the 1878 Lunacy Act had a significant effect on what is today the Cumberland Hospital Precinct.

The Act was a consolidation of two previously existing Colonial acts: the Act to Provide for Custody and Care of Criminal Lunatics of 1861 and the Dangerous Lunatics Act, 1868. [1]

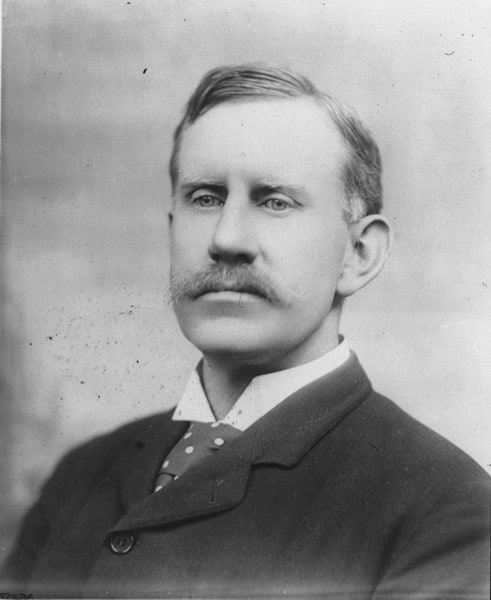

This later Act was heavily based on a comparative study of lunatic asylums and their conditions written by Dr Frederic Norton Manning, the then Superintendent of the Tarban Creek mental facility. The report did not reflect well upon the present state of Asylums and called for a radical overhaul of their management and methods of care. Essentially, Manning called for a more humane approach to caring for the insane. To achieve this, he wanted to

“secure for the management of such an asylum, the highest medical talent, the largest amount of experience, and the greatest benevolence.” [2]

Manning’s proposals also called for a professional inspector to oversee the institution, named the General Inspector of the Insane, who would have executive and legal capacity over the asylums of the State.[3]

On January 1, 1878, Dr Manning was appointed as the first Inspector General of the Insane in New South Wales. In a report he delivered on the Parramatta Asylum, Manning reiterated his criticisms of a decade earlier, especially those relating to the old Female Factory buildings. He noted the poor conditions of overcrowding with multiple patients often confined to a single cells and characterised the so-called “airing yards” as being “unpleasantly suggestive of arrangements at the Zoological Gardens.”[4]

Despite these criticisms, Terry Smith, a former Cumberland Hospital Nurse, noted that “following the proclamation of the Lunacy Act, The Parramatta Lunatic Asylum became known as the Parramatta Hospital for the Insane.” Smith explains that this change in terminology was a surprisingly significant marker, reflecting the changing attitudes towards mental health and its treatment.” [5]

Men of Vision: The Inspector-General for the Insane and the Architect

Executing Norton Manning’s plans to improve the quality and quantity of available accommodation and treatment facilities at the Parramatta Hospital for the Insane proved to be a slow process. However, by 1883, a large, single-story weatherboard complex had been built in the northern part of the old ‘Vineyard’ estate acquired from John and Ellen Blaxland, which had once the property of Reverend Samuel Marsden.[6]

Following Manning’s retirement as Inspector General for the Insane, Dr. Eric Sinclair was appointed to the role. Under his tenure, the site’s facilities continued to expand, with their layout reflecting the theories of Dr Sinclair himself, in their departure from overly institutional aesthetics. Instead, the new buildings were constructed under the principle that “build composition[s]” must “emphasise a community for homes within a predominately landscaped setting.”[7]

The area now known as the “Hospital for the Insane Precinct” is notable for being constructed from a single, integrated master plan in which access, buildings, and landscaping were coordinated as part of the broader hospital expansion from 1899 to the 1910s.

During this period, Dr. William Cotter Williamson, the medical superintendent of the Parramatta Hospital for the Insane, presided over a series of extensions located along the river bank to the north west of the existing weatherboard division, as well as numerous new wards, all under the direction of Government Architect Walter Lindsay Vernon.

Plans for a new Admissions and Hospital Block were prepared in 1908. According to an entry in the 1912 Public Works Report, contractor J L Thompson completed the construction for the sum of £8384. The report also noted that

“The erection of this building will complete the new mental hospital, which consists of two pavilions, one for male and one for females, an Administration block with accommodation for nursing staff on the upper floor” [8]

Dr Williamson also initiated a program in which patients themselves were involved in further beautifying the hospital grounds. By late 1911, the Precinct was described as “one of the show-places of Parramatta; and this is not at the expense, but the material benefit of the patients.”[9]

This construction phase also included a dedicated TB treatment facility on the pre-existing Asylum farm orchards.

The layout and form of the buildings features uniquely curved alignments, which reflect the curve of the river, where the ward buildings radiate out from the central axis of the Administration building. The departure from the “enclosure and isolation” paradigm of institutional structures allowed Vernon to design buildings that were designed as integrated “elements in a landscaped setting that related to and addressed the river and the campus.”[10]

Precinct Features

In 1893 Medical Superintendent Edwin Godson noted that many of the female staff still slept in rooms off the patients dormitories. He wrote of the need to provide a separate dining room for the nurses, and to provide a detached cottage, particularly for the night nurses, as they were constantly disturbed by noise during the day.[11]

Unfortunately this was not acted upon until 1911, when the Inspector General of the Insane reported that the “department had altered its policy concerning the accommodation of staff within the hospital for the insane,” deciding that staff accommodation should be positioned as far from patients as possible.[12]

Jacaranda House was constructed soon after, providing new nurses’ quarters as part of a series of hospital extensions that were carried out in the early twentieth century. The design was based on a suburban villa, with the ground floor accommodating two sitting rooms, a dining room, kitchen, pantry, and lavatory, while the upper floor featured another sitting room and several bedrooms for nursing staff.

Jacaranda House itself was surrounded by landscaped lawns and sat at the end of a camphor laurel-lined avenue to the south.

Admissions Building (currently the Transcultural Mental Health Centre)

This building was initially an admissions building, forming the axis from which the associated male and female wards radiated. Designed by Government Architect WL Vernon, with assistance from G McRae, it was completed in 1909. The building was designed to be in symmetry with its surrounds, and to be closely linked to the two adjacent ward buildings. The original portion of the building maintains its federation features and character, with gabled ends and a continuous veranda that looks out over the riverfront. In 1929, an x-ray plant was installed on the ground floor. This plant serviced all NSW mental hospitals.

Admissions Building, Parramatta Psychiatric Hospital c.1920

Source: State Library of NSW (bcp_01641r)

Female and Male Wards No.7 (Formerly the Wisteria Centre, currently the Centre for Addiction Medicine and Work skills Program Buildings)

The number 7 Female and Male Wards were also constructed in 1909 under the design of W.L Vernon. These buildings were constructed concurrently with the female ward to the north of the new Admissions building and the male ward sitting to the south at the junction of Eastern Circuit and Bridge Road. Each of these wards featured a continuous veranda along the western façade facing the river front and associated garden areas. The original buildings have now had a number of extensions, however the interiors still retain a number of original pressed metal ceilings, stained glass panels and curved bay windows. The modifications made in 1933 resulted in a new rectangular shaped wing at the eastern end of the male ward building. This was extended again in 1964 following the construction of a southern wing and additions to the south western end of the building. Similar modification were made to the female ward. Unfortunately, these modifications effectively enclosed the courtyards, and blocked the views from the original 1909 building to the river.

View from Male Ward veranda, facing towards Parramatta River, Source: State Library of NSW (d1_07744r)

TB Ward (Currently the New Street Adolescent Services)

Situated to the far north-west of the Admissions building, the current building occupying this site was constructed c. 1935 as a TB treatment ward. It replaced an earlier timber framed building that was burnt and demolished. Its location however, generally responds to Vernon’s master plan and is surrounded by landscaped lawns and a number of mature trees and plantings.

Timber Wharf/ Boat Shed

There is little known about the timber wharf and boat shed remains on the banks of Toongabbie Creek in this precinct. Perhaps it was utilized to move quickly between the upper precinct of the Parramatta Mental Hospital and the Wisteria Garden across the water. A similar wharf was constructed at the Gladesville Hospital to allow residents the opportunity to participate in short day-trips on the river.[13]

Glass House and Nurseries

These buildings are dated from approximately 1950 and are located on the river bank area that was previously part of the hospital farm. A resident reflected upon his time working in the hospital farm in the February 1952 Edition of the Wisteria Journal:

“It is with pride that I state that the vegetables grown in our garden constitute the greater part of our requirements, the only exception being potatoes, which are not grown here… We have growing at present vegetable marrows, pumpkins, spinach, tomatoes, beetroot, lettuce and onions. An orchard, which runs in conjunction with the vegetable garden. We have glasshouses for raising the delicate little seeding, and bamboo trellis on which we grow chokos”[14]

Extensions and Changing Purpose

Today, the vast majority of buildings found in the Hospital for the Insane Precinct have had significant alterations or additions to the original structures. However, these buildings have also retained a number of their original features and architectural qualities. The precinct thus continues to reflect the architectural and design innovations of its initial construction, and is still closely integrated within its Parramatta River setting

Catherine Thompson, Research Assistant, Parramatta City Council Heritage Centre, 2015

References:

[1] C J Cummins. “The Norton Manning Report”, A History of Medical Administration in New South Wales 1788-1973,(Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 1979) accessed 26 July 2015 http://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/aboutus/history/pdf/h-norton.pdf p.40.

[2] C J Cummins. “The Lunatic Asylums”, p.37.

[3] C J Cummins. “the Norton Manning Report”, p.41.

[4] Frederic Norton Manning, Parramatta Lunatic Asylum (1878) quoted in Terry Smith, Hidden Heritage:150 years of public mental health care at Cumberland Hospital Parramatta 1849-1999 (Westmead: Greater Parramatta Mental Health Services, 1999), p.18.

[5] Terry Smith, Hidden Heritage:150 years of public mental health care at Cumberland Hospital Parramatta 1849-1999 (Westmead: Greater Parramatta Mental Health Services, 1999), p.24

[6] Casey & Lowe, Baseline archaeological assessment & statement of heritage impact historical archaeology : Cumberland precinct, sports & leisure precinct, Parramatta north urban renewal – re-zoning , (Leichhardt : Casey & Lowe Pty Ltd. 2014) accessed 23 July 2015, http://urbangrowthnsw.com.au/downloads/file/ourprojects/6PNUREuropeanArchaeologyFINAL.pdf p.65

[7] Edward Higginbotham & Associates, Conservation Management Plan & Archaeological Management Plan: Cumberland Hospital East Campus & Wisteria Gardens (Ultimo: Perumal Murphey Alessi Heritage Consultants, 2010) pg.244

[8] Report of the Department of Public Works, for the year ending 30 June, accessed online 4 August 2015 https://www.opengov.nsw.gov.au/publications/11931;jsessionid=5226E51DAFBB379E0CCF0287BE00ECA9 p.32

[9] Margaret Betteridge, Parramatta North Urban Renewal and Rezoning: Baseline Assessment of Social Significance of Cumberland East Precinct and Sports and Leisure Precinct and Interpretive Framework, Randwick: Musescape Pty Ltd. 2014) accessed 25 June 2015, http://urbangrowthnsw.com.au/downloads/file/ourprojects/8PNURSocialSignificanceFINAL.pdf

[10] Edward Higginbotham & Associates, Conservation Management Plan & Archaeological Management Plan: Cumberland Hospital East Campus & Wisteria Gardens, p.244.

[11] T C Hou, Conservation Plan and Schedule for Works: Jacaranda House Cumberland Hospital (1991) quoted in Terry Smith, Hidden Heritage:150 years of public mental health care at Cumberland Hospital Parramatta 1849-1999 (Westmead: Greater Parramatta Mental Health Services, 1999) p.23.

[12] E Godson, “Hospital For the Insane Parramatta – Report” (1893) Journal of the Legislative Council 1894, quoted in Terry Smith, Hidden Heritage:150 years of public mental health care at Cumberland Hospital Parramatta 1849-1999 (Westmead: Greater Parramatta Mental Health Services, 1999) p.23.

[13] Wistaria Journal Quarterly Magazine for the Parramatta Mental Hospital, May, 1956, p.13.

[14] Wistaria Journal Quarterly Magazine for the Parramatta Mental Hospital, February 1952, p.13.