At 304 Pennant Hills Road Carlingford is a small reserve containing a memorial to those officers and men of the Commonwealth who gave their lives in submarines while serving the cause of freedom. This memorial, named the “K13” memorial, is particularly dedicated to those lost in HM Submarine K13, a steam-propelled World War One K class submarine of the British Royal Navy, which sunk in a fatal accident during sea trials in early 1917. The memorial was established in 1961 by the widow of Charles Albert Harry Freestone, a survivor of K13, who after leaving the royal navy emigrated to Australia and developed the prosperous business of C. A. Freestone Pty. Ltd. in Parramatta. The Parramatta district reminded him of Chelmsford where he was born. He set aside a part of his subdivision in Pennant Hills Road, Carlingford in 1956 for the memorial but died before he could realise his dream. Mrs M. F. Freestone, wife of Albert, took up the project and employed leading architect Douglas Snelling to design the memorial. The sculptor of the memorial was Gerard Lewers. The proposed memorial was adopted by Parramatta Council in March 1961.

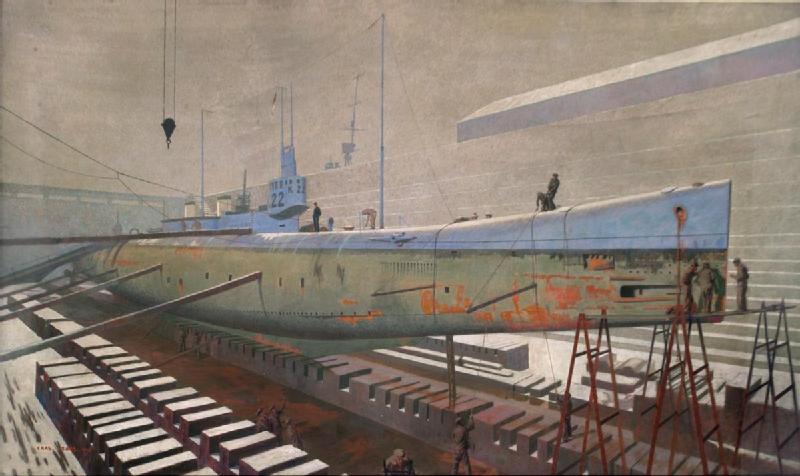

The K22 in Dry Dock. Six weeks after her fatal sinking the K13 was resurfaced and recommissioned as the K22

Below is an excerpt from a Sydney Morning Herald article by Charles Freestone recounting his remarkable escape from death.

PARRAMATTA MAN ALIVE TO TELL THE TALE

57 Hours in a Sunken Submarine.

REMARKABLE ESCAPE FROM DEATH!

By C. A. Freestone.

The K Boat.

…. I had been promoted to the dizzy height of a leading telegraphist and had the distinction of being the first leading telegraphist to be in charge of the wireless installation of a “K” class submarine K13 – which was being built, together with K14, by the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co., of Govan, Scotland, and was officially known as H.M.S. No. 522.

The K boats were the very latest in under water construction, being over 300 feet long with a displacement of over 1,800 tons.

January 27, 1917, was the appointed day for K13 to undergo her final acceptance trials which, if successful, meant that she would be accepted by the Admiralty, and handed over to the captain by the contractors who built the boat. These trials were being carried out in the Gareloch, off the west coast of Scotland. Besides the crew who were to commission the boat, numerous Admiralty officials and representatives of the contractors were on board K13 for these important trials.

After successfully diving in the forenoon to a depth of approximately 100 feet, K13 was brought to the surface, and a small boat, the Comet, came alongside to enable everyone go to aboard her for lunch. Immediately after lunch K13 dived again. It proved to be one of the most eventful dives in submarine history, as never before or since have men submerged for 57 hours in one dive in a submarine and lived to “tell the tale.” By a tragic oversight the boiler-room ventilators had been left open, and in a moment hundreds of tons of water flooded the after part of the boat, sweeping the entire engine-room staff into eternity. To prevent the complete flooding of the boat, bulkhead doors were immediately closed, and the remainder of the crew and the civilian authorities not in the engine-room found themselves trapped on the bottom of the sea in a half-flooded sub-marine, with half their mates killed.

Desperate Position.

Then began the longest 57 hours of my life. I do not believe that anyone expected to see Glasgow again, but there was not the slightest of panic, and a spirit of determination prevailed that every effort tried, however feeble, was better than no effort at all. Hour after hour of patient endeavour failed, but still the fight against overwhelming odds continued. Alter the first day we could hear surface craft sweeping for us above, and soon divers were sent and located our whereabouts. What a queer experience to be inside a sunken submarine and to hear divers walking about on the outside of the boat! One wondered what they were doing and whether they could possibly be of any assistance to us in time. It was at this juncture that Mr. Hillhouse, of the constructing firm, tore from his notebook a page with these words written on it: Can you fit seven-inch tube from officers vent to water surface for food and air?” This signal was made to the divers by myself by means of Morse code with a spanner on the hull of the boat. The message was repeated time after time.

Our position hourly was becoming more desperate. We were facing death by (1) starvation, there being no food whatsoever in the boat: (2) thirst, only a limited supply of water being on board: (3) suffocation, as the air was hourly getting worse and worse, and it hurt one to breathe; and (4) poisoning from chlorine gas when the salt water leaking from bulkhead reached the batteries. Only for the wonderfully patient way In which the representative of Messrs. Peter Brotherhood, of Peterborough, attended the pump for hours pumping out salt water bailed by us into a tank we would have been gassed long before. We knew, however, that the pump could not be driven when the battery failed, and that that was only a matter of a few hours.

A Bold Plan.

As the rescue workers were ignorant of the cause of our sinking, and therefore unable to put their maximum effort to practical use, our captain. Lieutenant-Commander Herbert, D.S.O., after conference with Commander Goodhart, D.S.O. (the captain to be of K14), decided on a bold plan. They were both to enter the conning tower, and after flooding the conning tower to obtain sufficient pressure to force open the lid Commander. Goodhart was to escape through the lld to thc surface, taking with him, in. the event of failure, a two gallon sealed tin, with the names of the living written therein, and also the best method to adopt to rescue them. Commander Herbert was immediately to close the lid after Goodhart had gone, drain the conning tower, and return to us in our compartment.

However, the pressure of air was too great; Commander Goodhart made the supreme sacrifice for his comrades, while Lieutenant Commander Herbert was blown up and reached the surface safely, and so was enabled to direct rescue operations with a first-hand knowledge ot the situation.

On the second day, the seven-inch tube was fitted and we were thus enabled to communicate with the surface. Immediately a flexible air hose was passed down the tube, so that the foul air in the boat could escape between the space surrounding the air hose. After this, a small bottle of brandy was lowered down the tube, the contents of which were issued out to each man in the top of a metal polish tin, holding approximately one tea-spoonful. An effort was made to lower a larger bottle down the tube, but it became jammed,and a leadline was lowered to break the bottle. That also became Jammed, and so the tube had to be disconnected, and we once again lost touch with the outside world.

Divers at Work.

Meanwhile, the divers had begun their colossal task, working continuously like Trojans in a bed of mud, as our stern was rapidly becoming more and more embedded in the mud, and hourly the task of raising the nose of the boat became more difficult.

On Wednesday night, after having been down since Monday afternoon, we could feel the boat beginning to adopt an angle. The nose was pointing upwards. Was the weight of the flooded stern dragging us down slowly and surely into deeper water? No; the work of the rescuers was bearing fruit; our nose was being lifted to the water line, our stern remaining on the bottom. Then came a sudden hiss and sparks, the flame of an oxy- acetylene blow pipe burning a hole in the boat, sufficient for the entombed crew to crawl through into the night. Wonderful fresh air and freedom after being prisoners for 57 hours at the bottom of the sea with half of the crew killed! We were then taken to the Shandon Hydropathic Hotel to sleep in a real feather bed, to bathe, and to drink soup-our first food since Monday. The cables lifting the boat parted soon after we were rescued, and she sank again….

References

Parramatta Man Alive to Tell the Tale. (1938, December 31). The Sydney Morning Herald p. 9. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27975407

Douglas Snelling Timeline – http://douglas-snelling.com/timeline/

http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/conflict/multiple/display/21052-k13-memorial