![Anzacs in France – the build up to Fromelles 1916 [Part One]](/sites/phh/files/styles/article_leader_image_style/public/article-images/An-Estaminet-within-800-yards-of-the-firing-line-at-Bois-Grenier-1916-The-Australian-War-memorial-No-EZ32-from-Charles-Bean-Official-Account-of-Australia-in-the-war-of-1914-1918-Vol-3-p.109-1080x675.jpg?itok=yGLKKEt_)

The beginning of 1916 also saw the Allies intent upon delivering, in spring or summer, an overwhelming concerted blow against Germany. For the officers destined for France it now became necessary for them to acquaint themselves with the British method of holding the Western Front, particularly in relation to the movement of divisions between the different army corps. Also communications were far more complicated due to the size and complexity of the units and because in the sectors near Armentieres most of the divisional headquarters were more than four miles, and corps headquarters no less than fifteen, from the lines.

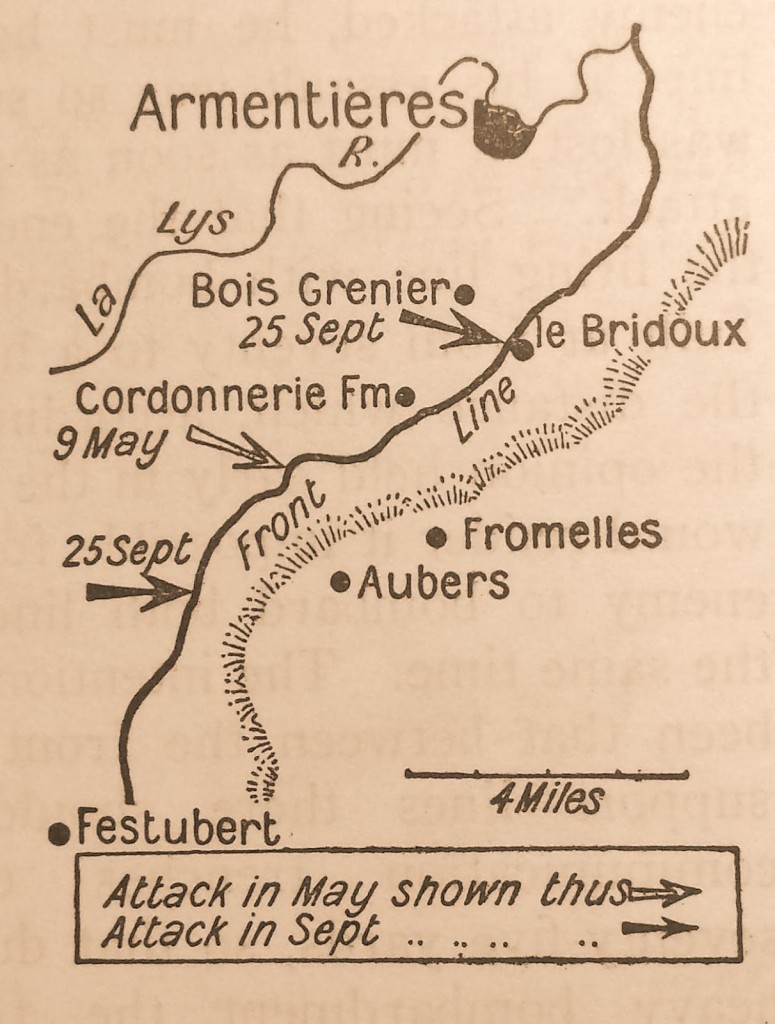

Map of Australian Position April 1916, from Charles Bean Official Account of Australia in the war of 1914-1918, Vol 3, p.109

On 4 April the 6 and 7 brigades, marching along the cobbled roads, reached Haverskerque and Oultersteene. Each brigade was for the first time marching with its full equipment, and was followed by its wagons and travelling kitchens. The troop initially had been,

… carried to the forward area in motor-lorries or old London omnibuses, painted grey, windowless, and dilapidated.’ The officers and men of the advance parties, almost all of whom had fought at Anzac, came to this new front like boys who go from a small school to a greater, with their eyes wide open, intending to learn all they could, somewhat anxious in facing for the first time the Germans.

As they neared the front the beautiful French countryside, and cheering crowds, gave way to the bleak and blasted landscape of war. After disembarking from their buses they trudged along the roadways and finally onto a … long winding path, at first only slightly sunken, but gradually appearing to sink deeper between two walls of earth and white sandbags, so that, in the course of half-a-mile, the green fields through which it was passing became completely shut out from view. The footway was now of wood-wooden boards nailed crosswise on longitudinal beams.

Once in the trenches those soldiers from Gallipoli almost immediately noticed three marked differences. Firstly the bare earthen walls of Gallipoli trenches would never stand unsupported in country so wet as France; second, that any excavation, however slight, would become waterlogged, and elaborate precautions were needed to keep the trenches drained and third the trenches in this sector were not really trenches at all, but rather passages between breastworks.

Another more welcome change was the fact that the clumsy improvised jam-tin bomb which the Anzac troops had fought with at Quinn’s Post and Lone Pine was now a relic of the past as they now had a plentiful supply of the deadly segmented Mills grenade.

On April 20th General Walker and his staff took over the divisional headquarters at Sailly and the Australian depots were established at Etaples. The two Australian divisions were by these stages brought into the line side by side, each with two brigades in the front line and one in reserve. On the 25 April the troops held their first commemoration of the landing at Gallipoli, which even then was commonly referred to as ANZAC day.

Another difference from Gallipoli was that the area behind the lines was stranger to them than those in the firing line. Here new experiences for those travelling to Europe for the first time abounded. These included: being billeted in the half-ruined Fleurbaix, within two miles of the front line, yet with a remnant of the inhabitants still living among them and selling them eggs and champagne at five francs a bottle; stepping out of a communication trench and strolling across a field to “Spy Farm,” sheltered by the trees only 800 yards from the line, where the old proprietor and his wife sold them beer as they sat round tables in the farm courtyard and visiting the well-kept tea-rooms in Armentieres.

Click here for Part Two of this post.

![]() Geoff Barker, Coordinator Research and Collection Services, Parramatta City Council Heritage Centre, 2016

Geoff Barker, Coordinator Research and Collection Services, Parramatta City Council Heritage Centre, 2016

References

Charles Bean, The Official History of the Australia in the War of 1914-1918 , Volume III, The AIF in France 1916, Angus and Robertson, 1941

![Anzacs in France – the build up to Fromelles 1916 [Part One]](/sites/phh/files/styles/image_1440x254/public/article-images/An-Estaminet-within-800-yards-of-the-firing-line-at-Bois-Grenier-1916-The-Australian-War-memorial-No-EZ32-from-Charles-Bean-Official-Account-of-Australia-in-the-war-of-1914-1918-Vol-3-p.109-1080x675.jpg?itok=UTC0frSo)