There was never an actual policy or law that was referred to as the ‘White Australia’ policy. Rather, the ‘White Australia’ policy refers to a range of policies which determined Australia’s approach to immigration from the 1850s, until its official abolition in 1973. This policy was defined by its attempts to restrict immigration of all non-Europeans, but specifically Asians, in order to maintain a population of largely Anglo-Celtic and European ethnicity.

For the first 5 or 6 decades of Australian history there was no restriction on immigration. In fact there was a general movement towards encouraging as much diverse immigration as possible, to compensate for shortages of labour in the new colony. There was a strong impetus towards encouraging Asian and Pacific Island immigration to develop agricultural resources.

However, with the new goldfields being discovered in the 1850s, a new wave of Chinese immigrants arrived in Australia seeking prosperity and a new life. This large influx of a very different cultural group that largely spoke no English, combined with fierce competitiveness on the goldfields, led to violence, demonstrations and riots. In response to this, the various states gradually introduced taxes on the Chinese immigrants, and passed legislation to restrict the number able to enter Australia. This culminated in an inter-colonial conference in 1888 which severely restricted Chinese immigration.

There were also many Pacific Islanders known as ‘Kanakas’ working in this period in the Northern Queensland sugar cane industry. Many workers felt that this represented a threat to current working conditions and this added to the general sense of opposition to foreign labour. Importation of these workers was stopped and many were repatriated under the Pacific Island Labourer’s Act of 1906.

In 1901 the separate self-governing colonies of New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia united to form the Commonwealth of Australia. One of the first Acts passed by the new Federal Parliament was the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, which was the culmination of all the previous restrictions on immigration. This Act did not specifically exclude people on the basis of race. That would have been seen as being too overtly racist for a country which was part of an openly tolerant British Empire. Rather, immigration was restricted through a method of inclusion and exclusion.

The method of inclusion was the active encouragement of immigration of Europeans, particularly the British, which included many forms of assistance.

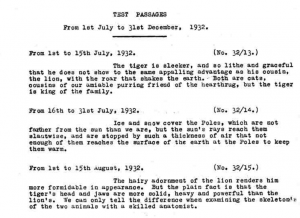

The method of exclusion was called the dictation test. According to the terms outlined in the Immigration Restriction Act, any applicant who failed to successfully write out a dictation, which was fifty words in length, and then sign it, could be denied entry into Australia, or immediately be deported without any ability to appeal.

These dictation tests were always in a European language, and the language deliberately chosen to make passing impossible, as can be seen in these select examples taken from the National Archives of Australia:

National Library of Australia NAA: Department of Immigration, A1, 1935/704

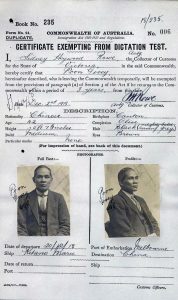

The Immigration Restriction Act had to allow for some flexibility so as to include people living in Australia for trade and education purposes, and also for people travelling in and out of Australia on a regular basis. Provisions also had to be made for families reuniting with people now residing in Australia. This flexibility took the form of certificates of exemption from the dictation test, which meant that compliance with this test was waived. This exemption was referred to as a Certificate of Exemption, and they provide much historical information on the applicant, as can be seen here in this example from the National Archives of Australia:

Certificate Exempting from Dictation Test. National Archives of Australia NAA: B13. 1918/25405

Certificates of Exemption were to allow temporary entry and could be cancelled if their conditions were not met. Extensions were possible, and there were instances where people managed to remain for many years subject to their need to reapply.

How these restrictions were felt on a personal level, are evident in a letter to the editor of the Parramatta newspaper The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers’ Advocate, in September 1922. On the first page it stated:

As the world knows that the Chinese businessman’s word is as good as his bond, I now appeal to the fair-minded, generous people of Parramatta not to be influenced by what our detractor’s state, but to judge us on our merits, and treat us in conformity with the principle of British fair-play and justice. Yours etc., “Chinese-Australian”

This system of immigration restriction remained relatively uninterrupted until the period just after World War II. Many Australian servicemen had married Japanese women, and they were being refused entry into Australia. Also the war had seen an increase in non-European refugees, and they were now being threatened with deportation. This implementation of the Immigration Restriction Act was unpopular with the Australian public, and with the election of the Liberal-Country party in 1949, the Act was overridden to allow the Japanese wives and non-European refugees to permanently live in Australia.

It was in 1956 that the first major alteration to the Act occurred when it was announced that non-Europeans who had lived in Australia for 15 years were allowed to apply for Australian citizenship. Also, non-European wives of Australian citizens could now apply for permanent residency. 1958 saw the introduction of the Migration Act 1958, which removed the dictation test from any application of residency. In 1966 restrictions were eased again to enable an easier transition from having only temporary residency to acquiring permanent residency and citizenship. These changes resulted in a substantial increase in non-European immigration to Australia.

The ‘White Australia’ policy is legally considered to have ended in 1973, when the then Whitlam Labour government formally announced a number of amendments to Australia’s immigration policy. These amendments notably included the official removal of race being considered in any immigration application. It also legislated that all migrants, regardless of race, were able to obtain citizenship after 3 years of permanent residence.

From 1973, Australia’s official immigration policy has ensured that race is no longer considered a factor in the eligibility of a potential immigrant to Australia.

References

Fact Sheet- Abolition of the “White Australia” Policy. http://www.border.gov.au/about/corporate/information/fact-sheets/08abolition

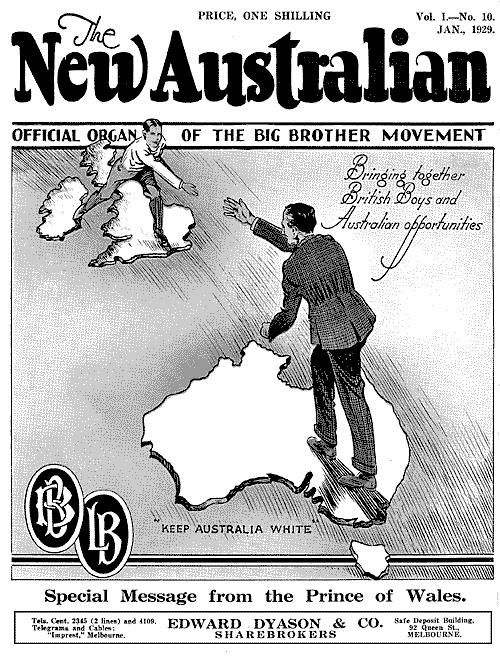

Image taken from the cover of The New Australian. National Archives of Australia NAA: A1.1932/7662

National Archives of Australia (NSW) http://guides.naa.gov.au/chinese/index.aspx

Personal correspondence with Dr Michael Williams, Adjunct Fellow, WSU.

The Alien Question: Letters to the Editor. (1922, September 30). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers’ Advocate (Parramatta, NSW : 1888 – 1950), p. 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103310040

The Australian Encyclopedia, Immigration (6th edition). (1996). Terry Hills, Australia: Australian Geographic Pty Ltd.

Caroline Finlay, Regional Studies Facilitator, City of Parramatta, Parramatta Heritage Centre, 2017.