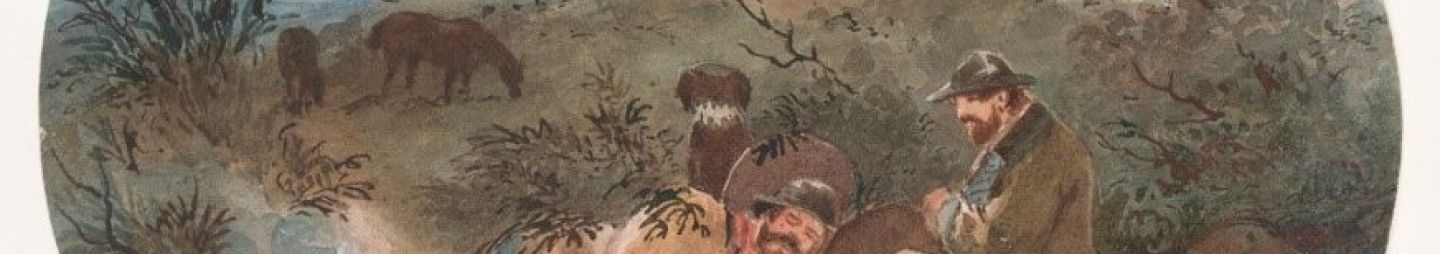

Bushrangers’ Camp by S T Gill artist, (1818-1880), c. 1871

From the time of the establishment of the European settlement at Sydney Cove in January 1788, members of the largely convict population attempted to break free from government control and regulation. As early as July of that year Governor Phillip reported to Lord Sydney that eleven males and one female convict had already gone missing from the colony in the few months since arrival1.

Living and working conditions in the colony made escape fairly easy as the colony was a prison ‘without walls’ and prisoners were not confined overnight. In addition, many were fleeing from the harsh conditions and inhumane treatment metered out by some superintendents of road gangs2.

These early escapees known as ‘absconders’ or ‘bolters’ attempted to survive without shelter or provisions, living off the land or by theft from stores. Some believed they could make their way back home through the bush while a small number stowed away on convict transports returning to England.

Most were apprehended and punished severely for their crime by execution, flogging or transportation to Norfolk Island, some perished due to starvation and exposure. Some were also able to survive for a period of time with the assistance of indigenous clans or complicit individuals.

The first mention of the term ‘bushranger’ may be found in the Sydney Gazette of February 1805 although it is assumed the term was in colloquial usage before this time.

On Tuesday last a cart was stopped between this settlement and Hawkesbury, by three men whose appearance sanctioned the suspicion of their being bush-rangers. They had been previously observed lurking about the Ponds by a carrier, who passed unmolested, owing perhaps to his having another man in company, they did not, however, take anything out of the cart they did stop, nor at this time has any account been received of their offering violence to either passengers or other persons, from whence it may be hoped they prefer the prospect of being restored to society to any momentary relief that might be obtained from acts of additional imprudence that could at best but render their condition hopeless. It is nevertheless necessary, that the settler as well as the traveller should be put upon his guard against assault, and that exertion should be general in assisting to apprehend every flagitious character who would thus rush upon a danger from which they can only be extricated by timely contrition and their return to obedience3.

Several years later the constant and recurring problem of predations by ‘free booters’ and ‘ruffians’ also known as ‘Bush Rangers’ especially in the settlement in Tasmania was acknowledged in a government dispatch from Governor Bligh to Lord Castlereagh in July 18094.

As the settlement in NSW increased in population and prosperity it became easier for convict absconders to evade the law and survive by robbery and stealth. The large tracts of thick bush between Sydney town and the outlying settlements such as Parramatta, Liverpool and Windsor provided many secure hiding places.

One of the earliest documented absconders was First Fleet convict John Caesar who came to be known as Black Caesar5. Thought to have been born in Madagascar, he made his way to London where he was convicted of theft and sentenced to seven years transportation to NSW. In December 1789, after a series of robberies, convictions and repeated escapes from custody, Caesar stole a canoe from Garden Island but gave himself up a month later at Rosehill.

In March 1790 he received a death sentence which was commuted to serving his original term in Norfolk Island. On his return to Sydney, Caesar reverted to his former life of habitual crime, capture and escape. Briefly hailed as a hero when he was credited with attacking Aboriginal leader Pemulwuy he soon returned to living by raiding the farms of settlers in the Parramatta district.

A reward was posted by Governor Hunter in January 1796 which prompted John Winbow and another man to track Caesar to his hide out near Strathfield. On 14 February 1796 Caesar was shot by Winbow and died several hours later.

Other bushrangers who frequented the Parramatta District between 1805 and the mid-1830s include John Murphy, John Donohoe (aka the Wild Colonial Boy), William Underwood, John MacNamara and George Kilroy (or Kilray), William Lynch, John Walmsley and William Geary.

From 1803, The Sydney Gazette newspaper published accounts of those who had escaped from government service or private farms warning of the severe punishments that awaited absconders who were recaptured6.

Travellers and private farmers were advised to be on their guard. Rewards for information leading to the capture of bushrangers usually consisting of a quantity of spirits acted as an incentive to citizens to report sightings while those tempted to assist or harbour the felons in their activities were promised severe penalties if caught.

During the 1820s Governor Darling made several orders in an effort to suppress bushranging activities in the colony, seemingly however, predations by bushrangers in the colony continued unabated. Punishment for accomplices and sympathisers was again reinforced by general orders in 18267. Troops were sent to outlying areas such as Parramatta and Bathurst to strengthen the observance of law and order and to increase the possibility of capture for those who had absconded from custody8.

By 1830 the activities of bushrangers had become widespread and significant. The Legislative Council of NSW passed an Act to Suppress Robbery and Housebreaking and the Harbouring of Robbers and Housebreakers9. The act gave police far-reaching and extensive powers to stop, search and arrest anyone under suspicion with onus on the alleged offender to prove innocence. The police also had the authority to search premises for stolen goods or evidence of the harbouring of bushrangers.

Draconian in its application, the act was widely resented by the public and questioned by subsequent governors such as Richard Bourke who deemed the act ‘contrary to the spirit of English law’, however it remained in force until 1853. Despite these misgivings, the legislation was re-enacted in various forms almost continuously up to 185310.

Transportation to New South Wales was discontinued in the 1840s and there was a gradual shift from convict absconders to colonial-born felons. The discovery of gold in Victoria and New South Wales in 1851 provided increased opportunities for those who chose to pursue a life of crime.

Cathy McHardy and Lyndall Linaker, Research Assistant, City of Parramatta, Parramatta Heritage Centre, 2017

References:

- HRA. Series I Vol I, 9 July 1788 p 47.

- West, Susan. Bushranging and the policing of rural banditry in NSW, 1860-1880. Australian Scholarly Publishing North Melbourne 2009 p 7.

- Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 17 February 1805 p 2.

- HRA. Series I Vol VIII 8 July 1809 pp 161-162.

- http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/caesar-john-black-12829 retrieved 22 May 2017

- Sydney Gazette, 26 March 1803 p 1.

- HRA. Series I Vol XII, 6 March 1826 pp 208-210.

- HRA. Series I Vol XII 4 May 1826 pp 208-210.

- http://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/acts/1830-11a.pdf retrieved 22 May 2017

- http://adb.anu.edu.au/essay/12 retrieved 22 May 2017

- http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/204714