From March to April 1918 sections of the Australian Imperial Force played an integral part barring the German offensive on Amiens, France. Among the many stories of courage and sacrifice that emerged from this engagement were two that relate directly to soldiers linked to the Parramatta and the surrounding district and which are described in Bean’s account.

In March 1918 the successful German advances on the allied lines around Villers-Bretonneux had reached crisis point ad on 29 March the 9 Australian Brigade had been detached from the 3 Division and ultimately made responsible for the safety of Villers-Bretonneux.

Next, in the crisis of 5 April, the 5 Brigade was ordered to take over the whole front between Villers-Bretonneux and the French lines. General Rawlinson noted in his diary … and I now have three brigades of Australians in reserve, so I think we shall be able to keep the Boche out of Amiens.

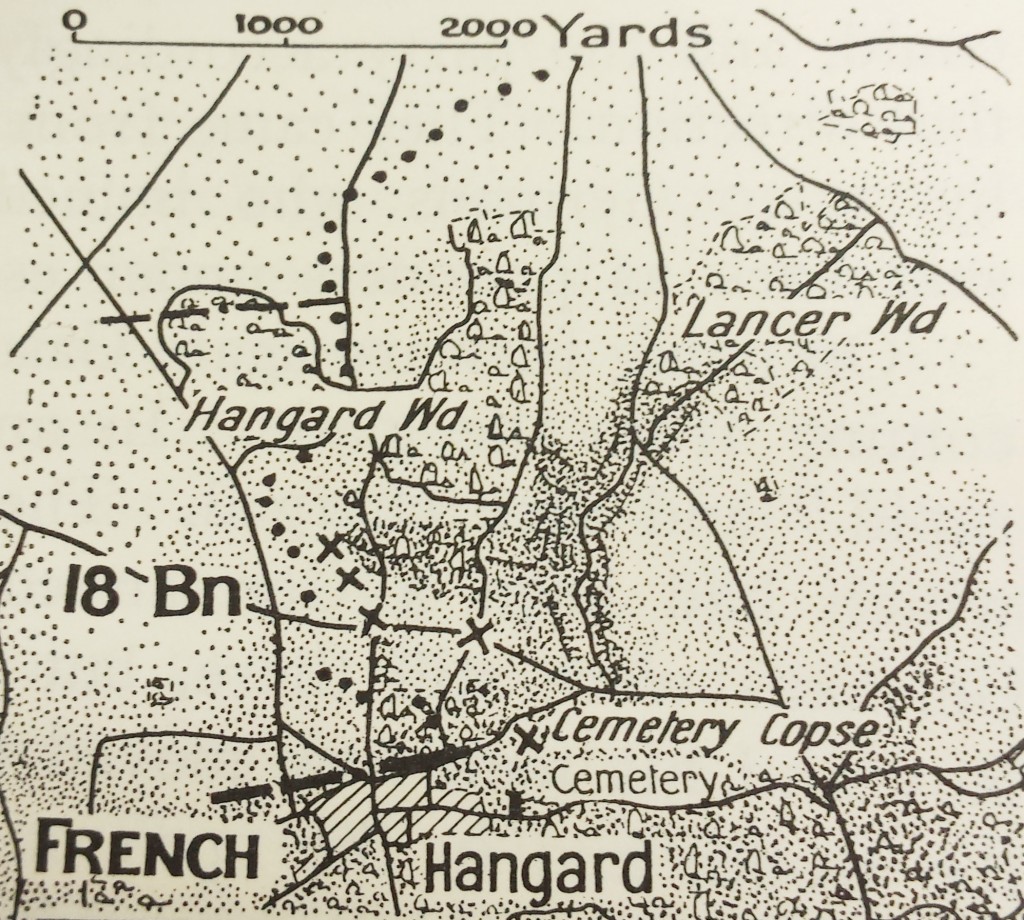

But the German offensive was still under way and because of their dangerous proximity to Amiens the Allied Commander, Foch, issued instructions for two counter strikes. One by the French in order to clear the Germans from part of the west side of the Avre, the other by the Fourth Army was to … clean up the woods and ravine north and north-east of Hangard Wood.

Germans were in these woods which extended for nearly a mile and comprised two unequal parts, the western small, the eastern large, the two being joined by a narrow neck like the handle of a dumb-bell.

During 5 April it was decided to use the 5 Australian Brigade to relieve all front-line troops and to straighten the line by retaking the eastern part of Hangard Wood. The morning of the 6 April found the front line of the Fourth Army under command of a British corps, the 111, but entirely held by Australian infantry, the 5 Australian Division.

The battle for Hangard Wood which started 7 April at dawn continued back and forth for days and involved hard and fierce hand-to-hand combat, gas attacks and even tanks. When the 19 and 20 Australian Battalions arrived on the slopes above the gully, the valley was being shelled, and it was again, at first, uncertain where the posts had been established.

Two days later on the evening of 9 April, Germans penetrated the nearby Hangard village and captured the cemetery east of it, they were in turn thrown out by a French counter attack but on 12 April the Germans began a heavy bombardment of the village and the hill to the north. The front of the 5 Australian Division was held by the 34 and 36 Battalions alongside the 7 Royal West Kent and 10 Essex Brigades.

On the north-east promontory the 36 under Lieutenant Colyer was stationed next to the French. But on the morning of this morning he was shot while walking back from the French lines and command of the outpost fell to Sergeant Laurie W Barber, from Granville, Sydney.

In the words of Bean … Sergeant Barber took charge of the post, but it was smashed in the bombardment and every man in it killed except Barber, who was buried but managed to work himself free. The valley at this stage was full of shell-smoke. Captain Gadd sent up his reserve Lewis gun crew to replace the one that had been lost. About 7 o’clock the smoke blew away and German infantry was seen pouring both from the north-east out of the southern end of Lancer Wood, and from the south-east by way of the wooded flats of the Luce, and converging upon Hangard village.

The S.O.S. signal went up and the French artillery concentrated upon the ravine in front of the 36th a bombardment so furious that an attack-by the 104th R.1.R. from Lancer Wood was split into parties which clustered, as if bewildered. Some nevertheless came along the northern flank of the spur against the right of the 36th, but were there swept with rifle and machine-gun fire, and fled, the attack on the northern slope being thus ended. In the Luce valley, however, the 107th R.I.R. had got into Hangard, the French being quickly driven from all parts except the chateau, which the Germans could not take. At this stage the French posts nest to the Australians began to dribble back, and proposed to retire to a position around the southern flank of the hill, overlooking the village.

They asked Sergeant Barber for the support of three Lewis guns to cover the withdrawal. Barber told them that the orders were not to retire except by command of the division which was, in effect, the arrangement made by General Debeney with General Butler (111 Corps) on April 6 … You dig in where you are (west of Hangard copse) and ‘box on’ with us,” said the Australians, “and we’ll give you all the help we can.” Lewis guns were turned upon the village; and, cheered by the Australians as they did so, the French rallied and went forward again to their posts behind the copse.

Shortly after this, about 10.15 a company of the Royal \Vest Kent was sent to the right of the 36th to co-operate with the French in an immediate counter-attack. The French did not get into Hangard. Part of the Royal West Kent, on coming under fire on its way to the Australian front line, wavered, but about half the company went on and dug in behind the junction of the 36th and the French. So matters remained until 6.30 p.m. when the Germans, reinforced in the village, took the chateau, capturing 75 Frenchmen and releasing some Germans.

Immediately afterwards the Germans noticed that in the copse above the village, where the British and French lines joined, there was a stir foreshadowing a counter-attack. At 7 the French artillery threw a bombardment on the village, and at 7.20 the 10th Essex who had come steadily up over Hill 99, went straight through the German position, as did the French on their right. The Essex lost more than half their strength, but held on.

Hangard was retaken but not the cemetery or the copse 200 yards north-east of the cemetery. This fighting caused the abandonment of the project as a combined attack which the French and the 111 Corps were to have made next day.

Neera Sahni, Research Services Leader, City of Parramatta, Parramatta Heritage Centre, 2018

References

The biographical information has been researched and compiled from the following resources:

- Australian War Memorial – https://www.awm.gov.au/

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission – http://www.cwgc.org/

- National Archives of Australia – http://www.naa.gov.au/

- National Library of Australia Trove Digitised Newspapers Database – http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper

- Parramatta and District soldiers who fought in the great war, 1914-1919. (1920). Parramatta, N.S.W. : The Cumberland Argus Ltd. – https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9iAn5sxT0i8ZHgyZjR2UHRxVUU/edit

- The National Archives (UK) – http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

- University of New South Wales Canberra The AIF Project – https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/index.html

- Charles Bean, The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Volume Five, The AIF in France December 1917 to May 1918, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1937