Portrait of Sydney Evan Jones as a medical student, c.1910. Source: Friends of Mays Hill Cemetery Photograph Collection

The ground-breaking career of Dr Sydney Evan Jones (1887-1948), one of Australia’s earliest psychiatrists and doctor on Sir Douglas Mawson’s expedition to the Antarctic, has strong connections to the Parramatta area. Parramatta is also Dr Jones’s final resting place.

A brilliant and innovative medical professional, Dr Jones was an early practitioner of psychotherapy, revived the application of animal assisted therapy, and actively promoted the importance of calming and attractive surroundings when treating mental health illnesses.

Early life

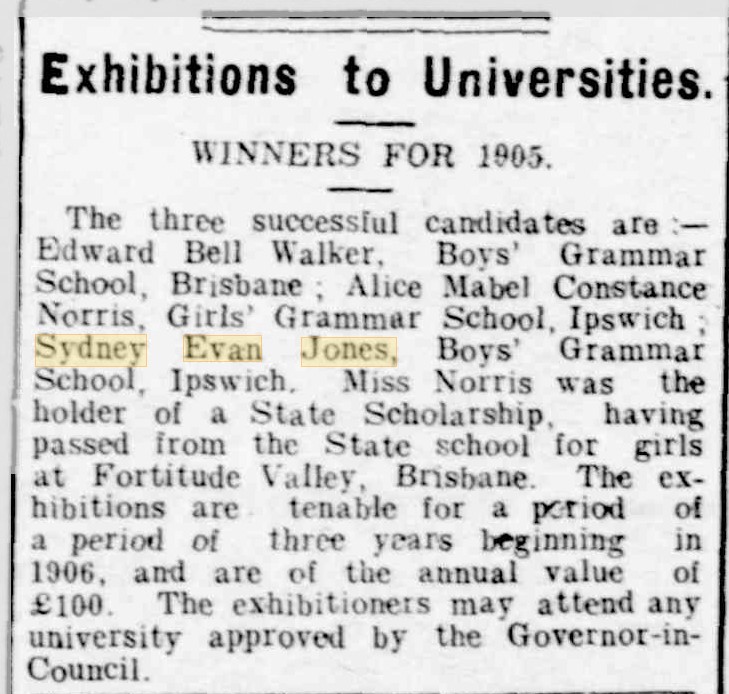

Sydney Evan Jones was born in South Australia in 1887. Shortly after, his family moved to Queensland, where Sydney attended Boys’ Grammar, Ipswich. A brilliant student, on graduation in 1905, Sydney won a scholarship to attend university.[1] From 1906 until 1910, he studied Medicine at University of Sydney.[2] On graduation in 1910, Dr Jones was appointed Resident Medical Officer at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney.[3]

A brilliant student, Sydney Evan Jones was awarded a scholarship to attend university in 1905. Source: Gympie Times and Murray River Mining Gazette, 21 December 1905, p.3

One of “Mawson’s Men”

At Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, the young Dr Jones worked closely with another University of Sydney graduate, Dr Archibald McLean. In 1911, both young doctors joined Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition.[4]

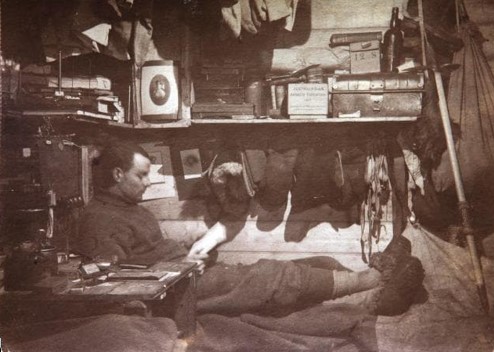

A practical man, Dr Jones’s contributions to the Antarctic expedition were not confined to medical duties – he helped construct the famous hut named ‘The Grottoes’, as well as an igloo for a magnetic observatory. Jones also contributed to The Glacier Tongue, the station’s publication, and was the camp plumber and cook. It is said thoughts of marrying his beloved Olive Booth, whose image hung beside his bed at Base Camp, on his return “sustained Jones during the most difficult times”.[5]

Dr Jones in camp at the Antarctic, with a photograph of his fiancé, Olive Booth, hanging beside him. Source: State Library of New South Wales

The ‘New South Wales Mental Hospital Branch’

On return from Antarctica, perhaps inspired by his friend and colleague Dr McLean’s challenges treating episodes of paranoia and delusions at Main Base in Antarctica, Dr Jones decided to study and practice as a psychiatrist.[6] In 1914, Dr Jones joined the New South Wales Government Mental Hospitals Branch. His first appointment was as a Junior Medical Officer at Parramatta Asylum for the Insane, where he treated patients traumatised by their experiences on the battlefields of the First World War.[7]

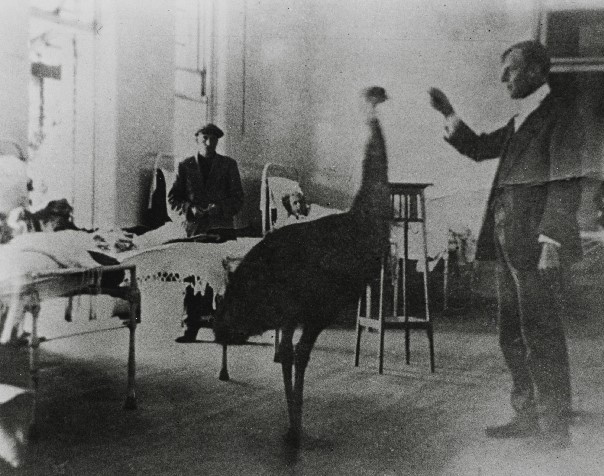

An early example of animal assisted therapy, in a ward of the Parramatta Asylum for the Insane, c. early-1900s. Source: City of Parramatta Local Studies Photograph Collection, ref: LSP00060

Marriage and tragedy

In February 1915, following a long engagement, Dr Jones finally married his fiancé, Olive Booth. Sadly, little more than 18 months after their wedding Olive, aged only 23, died from complications following the birth of their daughter. The child survived, and was given the name Olive in honour of her mother.[8]

Olive Booth at her wedding to Dr Sydney Evan Jones, 1915. Tragically, Olive died in childbirth a little over a year later. Source: ACT Museums and Galleries

Following Olive’s death, Dr Jones transferred to Rydalmere Hospital for the Insane, again as a Junior Medical Officer.[9] The building, originally the Female Orphan School, had undergone extensive renovations in the 1890s to accommodate patients with mental health illnesses. Particular emphasis had been placed on the natural environment around the building in the belief that this would assist the recovery of patients. The land around the building was landscaped extensively – in 1893, the Royal Botanic Gardens donated hundreds of trees and shrubs to improve the gardens on the site.[10]

Broughton Hall and pioneering therapies

By 1920, Dr Jones had accepted a post as Medical Officer at Callan Park Mental Hospital, and in 1921 he was appointed Government Medical Officer at Broughton Hall Mental Hospital, on the site now known as Rozelle Hospital. Having initially served as a hospital for soldiers returned from the First World War, the buildings had been re-opened as a voluntary admission mental health clinic.[12] In 1925, Dr Jones was promoted to Medical Superintendent of Broughton Hall.[11]

Drawing from experiences during his years of training at the Parramatta and Rydalmere hospitals, Dr Jones began to develop pioneer treatments of mental illness at Broughton Hall. Seeing voluntary patients who had previously avoided treatment because of the stigma of mental health certification, the clinic introduced various new ‘occupational therapies’ of short timescales, moving away from earlier mental health hospital models of segregation and long-term incarceration.

Dr Jones spent part of his formative early career in psychiatry at Rydalmere Hospital for the Insane, c.1910. Source: City of Parramatta Local Studies Research Library, Ref: LSP00744

The importance of animals and gardens also figured prominently in Dr Jones’s treatments at Broughton Hall. Although the value of animal assisted therapy is believed to have been recognised in the earliest of human societies, the first formally documented use of the therapy applied to the mentally ill took place in the late 18th century at a retreat in England, where patients were allowed to wander the grounds shared by a population of small domestic animals.[13]

Adopting this approach at Broughton Hall, Dr Jones created grounds incorporating a fish-bearing stream, ornamental bridges, and a planted forest. Later, embracing the practice of animal assisted therapy, zoological gardens were created with peacocks, kangaroos, emus and other Australian fauna, as well as a well-stocked aviary. Over time, with changes to mental health treatment practice, the zoo was closed and the animals were dispersed. The last of the zoo structures, the Kangaroo House, was eventually demolished, in 1972.[14]

Death and legacy

Broughton Hall became Australia’s largest facility for treating voluntary mental health patients. The establishment of a chair in psychiatry at the University of Sydney at the same time as Dr Jones’s appointment to Broughton Hall allowed the clinic to take on undergraduate students, making a generation of Australian psychiatrists aware of his work. In 1963, his contribution to psychiatry was recognised in Broughton Hall’s new Evan Jones Lecture Theatre.[15]

Dr Jones also played an important role in the professional membership body for psychiatrists in Australia. He led the neurology and psychiatry section of the British Medical Association (NSW Branch), and then became a foundation member of the Australasian Association of Psychiatrists when it was formed in 1926.[16]

In summary, a brilliant medical graduate, Dr Jones played an important role as one of ‘Mawson’s Men’ during the famous Australasian Expedition to the Antarctic in 1911 to 1914. Choosing to study and practice in the newly-developing speciality of psychology on his return, Dr Jones spent his formative training years at ‘hospitals for the insane’ in the Parramatta area. In the 1920s, Dr Jones established the pioneering Broughton Hall Mental Health Clinic, where he introduced innovative treatments including animal assisted therapy and occupational therapies. Dr Jones also promoted the positive outcomes of green and pleasant environments in the treating of troubled minds.

A young Dr Sydney Evan Jones as one of “Mawson’s Men” on the Antarctic Expedition, c. 1911. Source: National Library of Australia

Dr Jones died of cancer in his residence at Broughton Hall in 1948. Although he had remarried twice following the premature death in childbirth of his first wife thirty years earlier, he chose to be buried next to Olive at Mays Hill Cemetery.[17] His sandstone memorial, with scrolled sides and white marble top reads simply, and modestly, ‘Sydney Evan Jones 1887-1948’.[18]

Timeline of life

1887 – Born in South Australia, shortly after family moves to Queensland

1905 – Graduates from Boys’ Grammar School, Ipswich – wins scholarship to attend university

1910 – Graduates from Medicine at University of Sydney

1910 – Appointed Resident Medical Officer at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney

1911 – Joins medical team on Sir Douglas Mawson’s expedition to the Antarctic

1914 – Joins the New South Wales Government Mental Hospitals Branch

1914 – Serves as Junior Medical Officer at Parramatta Lunatic Asylum

1915 – Marries Olive Booth

1916 – Death of Olive from complications after childbirth

1916 – Appointed Junior Medical Officer at Rydalmere Hospital for the Insane

1920 – Appointed Medical Officer at Callan Park Mental Hospital

1921 – Appointed Government Medical Officer at Broughton Hall Mental Clinic

1925 – Appointed Medical Superintendent of Broughton Hall Mental Health Clinic

1946 – Foundation Member of the Australasian Association of Psychiatrists

1948 – Dies of cancer at Broughton Hall and is buried at Mays Hill Cemetery

Michelle Goodman, Archivist, (with additional research by Elise Watts, Research Assistant), City of Parramatta, 2018

References:

[1] Exhibitions to Universities. Winners for 1905. (21 December 1905) Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette p.3

[2] https://dictionaryofsydney.org/person/jones_sydney_evan [accessed 22 May 2018]

[3] http://www.antarctica.gov.au/magazine/2011-2015/issue-22-2012/mawsons-men/mawsons-men, [accessed 29/5/2018]

[4] Sydney Evan Jones (2014) Australian Government. Department of Environment and Energy, Australian Antarctic Division http://mawsonshuts.antarctica.gov.au/western-party/the-people/sydney-evan-jones (last modified 3 July 2014) [accessed 22 May 2018]

[5] http://www.antarctica.gov.au/magazine/2011-2015/issue-22-2012/mawsons-men/mawsons-men, [accessed 29/5/2018]

[6] http://www.antarctica.gov.au/magazine/2011-2015/issue-22-2012/mawsons-men/mawsons-men, [accessed 29/5/2018]

[7] http://www.antarctica.gov.au/magazine/2011-2015/issue-22-2012/mawsons-men/mawsons-men, [accessed 29/5/2018]

[8] Friends of May’s Hill Cemetery Facebook page, [accessed 24 May 2018]

[9] Fractured Skull. Death at the Hospital of the Insane. (14 June 1916), The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p.2

[10] https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/femaleorphanschool/home/rydalmere_psychiatric_hospital_1888_to_1989

[11] Sydney Evan Jones (2014) Australian Government. Department of Environment and Energy, Australian Antarctic Division http://mawsonshuts.antarctica.gov.au/western-party/the-people/sydney-evan-jones (last modified 3 July 2014) [accessed 22 May 2018]

[12] Sydney Evan Jones (2014) Australian Government. Department of Environment and Energy, Australian Antarctic Division http://mawsonshuts.antarctica.gov.au/western-party/the-people/sydney-evan-jones (last modified 3 July 2014) [accessed 22 May 2018]

[13] Serpell, James (2000). “Animal Companions and Human Well-Being: An Historical Exploration of the Value of Human-Animal Relationships”. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice, pp. 3–17

[14] https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/broughton_hall_psychiatric_clinic, [accessed 24/5/2018]

[15] Serpell, James (2000). “Animal Companions and Human Well-Being: An Historical Exploration of the Value of Human-Animal Relationships”. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice, pp. 3–17

[16] Sydney Evan Jones (2014) Australian Government. Department of Environment and Energy, Australian Antarctic Division http://mawsonshuts.antarctica.gov.au/western-party/the-people/sydney-evan-jones (last modified 3 July 2014) [accessed 22 May 2018]

[17] Dunn, Judith (1996). The Parramatta Cemeteries Mays Hill. Parramatta and District Historical Society. p. 43

[18] Dunn, Judith (1996). The Parramatta Cemeteries Mays Hill. Parramatta and District Historical Society. p. 43