Staff at Parramatta District Hospital, c. 1890 (Source: City of Parramatta Council Local Studies Photograph Collection, LSP00098)

Background

It can be assumed that Principal Surgeon John White planned hospital facilities at the new settlement at Rose Hill in a similar way to those at Sydney Cove on the landing of the First Fleet.

The primary settlement saw about 800 convicts landed, many boarded in poor health from their long imprisonment in the hulks. Outbreaks of dysentery and scurvy, when they were landed required temporary hospital facilities in tents. Within a year however, the incidence of sickness was greatly reduced and a temporary hospital built by 1790

With the governor’s announcement that he intended to form an agricultural settlement at the head of the harbour, White, who was a member of the expedition that had discovered the site, planned his staff and accommodation there. He chose his senior surgeon, William Arndell to be in charge at the settlement.

At Sydney Cove, Phillip’s immediate building priorities had been in the erection of store buildings to receive the stores from the ships and a hospital to receive the sick who had been accommodated in tents on the west side of the Cove. Under Henry Brewer, he utilised the twelve convict carpenters and hired the sixteen shipwrights to construct these buildings. The hospital was 84ft by 23ft, of timber, covered with split pine shingles fastened with wooden pegs fashioned by female convicts. It was located in the vicinity of the former Maritime Services Board building and it appears that the same type of building was erected at Rose Hill.

In June 1790, with the arrival of the Justinian, a store ship of the Second Fleet, which in addition to a large number of sick and dieing convicts, bought their salvation in the form of a portable hospital building purchased by the government from Samuel Wyatt at the cost of £690. Comprising 602 pieces, this ‘moveable hospital’ measured 84ft by 20ft 6ins and was 12 ft high. It comprised wooden framing in panels, with cross partitions and porches with a roof covered by copper.[1]

THE FIRST HOSPITALS

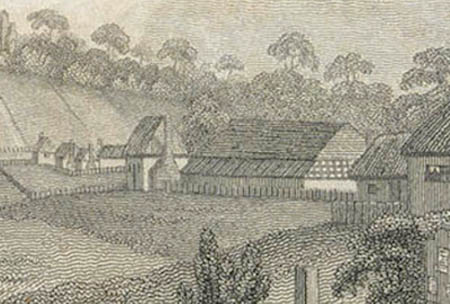

The ‘Tent’ Hospital at Parramatta, c. early-1790s (Source: State Library of New South Wales)

The ‘Tent’ hospital: 1789

The site of the first ‘hospital tent’ at Rose Hill to accommodate outbreaks of dysentery among convicts would have been on the flat site, east of the Moat Creek, where the convict party was camped. The military guard who required medical attention would have been accommodated in the Redoubt complex. As it was only a few hours downstream to Sydney Cove, problem cases would have been removed to the hospital there. No doubt, the convicts chosen to work at Rose Hill would have been chosen from the strongest and healthiest available, preferably those with some agricultural experience such as James Ruse.

Location

The first built hospital at Rose Hill was located on the northern side of the High Street (now George Street), the first formed road at the settlement, approximately between today’s Marsden and O’Connell Streets, set back from the original track, which later became the formed street. Traditionally, hospital buildings since that time have occupied this site. It may be seen in the drawing, A View of the Governor’s House at Rose Hill in the Township of Parramatta.[2]. Fletcher describes the scene in part ‘To the right of the street were other convict huts, barracks for the military garrison, a store and a hospital’. There is evidence that the convict painter Thomas Watling ‘had a hand’ in sketching the original scene. Helen Proudfoot, who also uses the illustration, claims that there is a likeness to Watling’s east view of Port Jackson and Sydney Cove taken from behind the New Barracks, a painting in the British Museum, signed by Watling.[3]

The map of the settlement of 1790 does not locate the hospital by site but gives us two clues that are marked, and confirms Fletcher’s observation to its position – Hospital Lane and the Surgeon’s House.[4]

Description

The first description came from Captain Watkin Tench RM in mid November, 1790;

A most wretched hospital, totally destitute of every conveniency. Lucky for the gentleman who superintends this hospital [Thomas Arndell] and still more lucky for those who are doomed in case of sickness to enter it, the air at Rose Hill has been generally healthy. A tendency to produce slight inflammatory disorders from the rapid changes [in temperature, between dawn and dusk] of the temperature of the air is most to be dreaded.[5]

Tench goes on to state that on one particular day in summer, that the sick list contained the names of 382 persons. Twenty five adults and two children died during that time. At the end of the year 1788, the thermometer recorded temperatures of 50 F a little before sunrise, and between one and two o’clock in the afternoon at above 100F. The first settlers were experiencing he first drought in the Colony’s history:

The prevailing disorder is a dysentery which often terminates fatally. There was lately one very violent putrid fever which by timely removal of the patient was prevented from spreading.[6]

The hospital comprised two long sheds, built in the form of a tent, and thatched.

It was a roughly built structure, capable of accommodating two hundred patients, the number being confirmed by Tench in December 1791. [7] The hospital probably began as a large tent structure, the sides of which were gradually replaced with timber, and the roof with thatch. It was 80 feet in length and 20 feet wide. Surgeon Arndell was in charge and he was assigned a convict as a personal servant and two convicts to nurse the sick. The hospital could contain 200 patients.

Dr Keith MacArthur Brown, a descendant of a family of doctors who began private practice in Parramatta in 1857, lectured on the subject of early medical practice in the colony at Sydney University. He described the early medical scene in Parramatta, in his book and claims that from the little information handed down to us, that hospitalisation of the sick and suffering in those early days was appallingly crude and incompetent. This is supported by Tench’s statement. Brown claims that the hospital was:

intended as a dumping ground for afflicted convicts, or a refuge for those settlers, their wives and children, who were known to be without visible means of support’; so that a high standard would not becontemplated in providing for their care and comfort.[8]

Brown then makes the observation that many of the early surgeons were pre-occupied with agricultural pursuits and other official duties, as distinct from their professional responsibilities, often making their medical duties of secondary consideration.

The second Parramatta hospital: 1792-1818

In April 1792, Phillip laid the foundations of two new buildings at Rose Hill, a town hall and a hospital. The town hall was planned to include a market place for the sale of grain, fish, poultry and live stock, clothing and any other items that the convicts might wish to buy or sell. [9] The necessity for a new hospital however became a priority and tempered Phillip’s plans for his grand square and town hall; he ordered that the hospital be completed first. Planned with two wards, one each for male and female patients, the hospital was built of locally made bricks and was finished in December 1792 when the sick were immediately removed to it. [10] As Phillip returned to England ill in the same month, plans for his town hall, treasury and public library contained in a great market square went back to England with him as a vision as they never materialised under succeeding administrations.

Location

Located a distance away from High Street behind or to the north of the first hospital, the new infirmary was about 100 meters from the river bank, ‘convenient to the water’, To prevent ‘any improper communication with other convicts,’ it was enclosed with a paling fence, with space around the hospital ‘so that the sick would have every advantage of both air and exercise’.[11] This meant that the two original hospital buildings were within the grounds of the today’s hospital perimeter.

Confusion existed with earlier historians as to this location of the second hospital and should be clarified. When Watkin Tench recorded in his journal of new buildings being planned in the town, he wrote of a plan (east of the Barrack Lane on High (George) Street) for a blacksmith’s shop, a carpenter’s shop and nine covered sawpits.[12] He also mentions the ‘wretched’ hospital with these improvements but its location has been misconstrued as being nearby. JF Campbell, noted surveyor and historian, located the barn-yard of the Government Farm on the spur on which Macquarie’s Convict Barracks once occupied on the Barrack Lane between Macquarie and George Streets.[13] Many historians have accepted the myth of the hospital being located here but there seems to be little evidence to support this site.[14] Andrew Houison (1850-1912), one of Parramatta’s earliest historians appears to have been the first to record it in 1903 and since then it has been accepted without question.[15] Keith Macarthur Brown, possibly accepting Houison’s word, even locates the first hospital to be there, ‘on the present site of the Macquarie Street Home’. By this he means the Macquarie convict barracks which became later a hospital for erysipelas patients and the then a refuge for aged men, referred to as the ‘Macquarie Street Home’. Perhaps the erysipelas hospital was construed to mean the second hospital.[16]

Logically it would have been ill conceived here and more likely to have been in the Hospital Lane as shown in the early map.[17] Richard Rouse, giving evidence to Commissioner Bigge in 1821 as Superintendent of Government Works, refers to ‘[patients in liquor] lying about the hospital when I was building the new one’. The ‘new one’ was Macquarie’s hospital, leaving little doubt that the old hospital was in the vicinity, ‘near the water’ and not in Macquarie Street.[18]

Description

The second built hospital at Parramatta was of brick on brick foundations, 80 feet long and 20 feet wide. It comprised a ward at each end with a cross passage between them, the entrances to which were open. The roof was a continuous gable and thatched until it was tiled with plain hand formed tiles, which were really thin bricks as they were manufactured from the same clay and burned to the same temperature as bricks. There with windows along the walls, of small panes, in timber frames which gradually deteriorated with age. Panes of glass were often replaced with wooden squares and after a time, these could not be repaired as the timber was rotten and would not stand further repair. As the brickwork was bonded with mud mortar due to the lack of lime, it could be expected that life of the building was limited.

Outbuildings such as stores, convict staff accommodation and latrines were close by while the surgeon was provided with a separate house. Hygiene was ignored, leading to putrid smells and odours and no doubt led to further illness and disease of patients. There was no morgue nor constant stock of coffins, the responsibility for their supply was that of the Supervisor of Government Works.

Cooking was done in a separate kitchen. Surgeons reported that there was never sufficient invalid food such as tapioca and portable soup while mostly the ill were supplied with the same rations as other convicts and there were constant reports of theft. Medical supplies and blankets were constantly in short supply, either through a shortage from the medical stores at Sydney Town, or in some instances, neglect by the surgeon in charge to requisition them.

In 1803 Surgeon Balmain drew to the attention of Governor Hunter the ‘extreme distress of the hospital [s] for the want of medicines, necessaries, bedding, stationery and all kinds of utensils, demands for all of which … have been pressingly made by me upwards of two years since, and none of them have yet been answered’. One can understand that the home government would be tardy in providing hospital necessities for ‘dumped’ convicts but they were forgetful of the other members of the colony who were reliant on the hospital to cure their ‘hurts and sicknesses’.[19] At least Balmain had a new military hospital and dispensary built in Sydney.[20]

The organisation

Convicts selected to assist in the hospital were those usually too old or infirm to undertake arduous duties in the normal workforce. Women convicts, for whom tasks in the colony were limited, predominated but sometimes duty at the hospital was used as a punishment for misdemeanours. Deployment of convicts in 1806 show that seven convict men filled the tasks as overseer, wards man, gardener and wood chopper while the roles as nurses were undertaken by seven convict women. No reward was given to them for this work other than their usual living allowances of food. It was Surgeon Major West who first drew to the attention of the administration of the difficulties that he had in getting the convicts to undertake their assigned work at the hospital for unlike others, they would have preferred to work for settlers and officers and gain some remuneration for their extra hours worked. Even the overseer, he claimed, ‘the most confidential person in the hospital, and clerk’ received no remuneration. Also, the nature of the staff employed led to constant theft of blankets and bedding, food, and even medical supplies, such as a case later to be exposed during the Bigge Inquiry.[21]

During his term of office, Governor King laid down the functions of the convict hospitals specifying that they were to treat all persons of the civil department, convicts and all government employees. This included the military as well as convicts assigned to settlers. This order made no provision to receive free settlers or specify that surgeons were allowed the right to private practice for fees. This created problems as was recorded about Mileham and Savage who were both court martialled for not attending settlers. At least, theses cases resolved the problem and the administration in London allowed limited right of private practice. Unfortunately this too had its abuses.[22]

Within fifteen years the brick walls of the building showed critical signs of deterioration to the point that the walls were in danger of falling and repairs were of little use. By 1803, Wentworth advised the Principal Surgeon of the dilapidated state of the hospital that ‘needed complete and speedy repairs’.[23]

In 1814 the surgeons petitioned Earl Bathurst on their dissatisfaction with their situation compared to medical officers in the army and navy. They were concerned about their terms of pay, servants, fuel, rations and pensions for their widows but in particular in the lack of an allowance for a horse. They were required to maintain one so as to be able to:

perform the duties of the respective hospitals … but to attend, in their own houses, the civil officers, their wives and families, and also the convicts who are distributed to the various settlers, scattered over the country at considerable distances from each other and from the quarters from the different medical officers, without any fee or compensation.[24]

In regards to the conditions in the hospital, Samuel Marsden helped to bring matters to a head by writing to Earl Bathurst direct. He was mainly concerned about reports of debauchery in the hospital but was comprehensive in his letter, claiming:

This hospital is open night and day for every infamous character to enter, there are no locks or bolts to any of the doors …There is not so much room as to put dead man or woman in till they can be removed to their grave; but the dead lie in the room with the living patients … the patients are distressed for weeks and months for the want of common necessaries … they were frequently without sugar, rice, tea and wine, or any other support than from the King’s Store, which consists of wheat and animal food which from sickness many of them could not use. I also observed that there had not been a candle or a lamp for the last two years to see a patient die. Often when I have been called on to visit the hospital after dark, I have had to grope my way to the sick man’s bed. I do not believe that there was ever such a place for want, debaucheries and for every vice as the general hospital at Parramatta.[25]

The evidence of the Bigge Report

The evidence of Richard Rouse, Superintendent of Government Works, and Senior Chaplain Samuel Marsden taken from the Bigge Report give the most factual details of the state of the second hospital. Rouse described in his answers to the Commissioner’s questions that the building itself was about 80ft long and 20 broad. It had been enclosed ‘ a long time ago’ but the enclosure had decayed. There was no outside door to the passage but there were doors to each ward, but Rouse could not recall any locks on them.[26] When asked if men and women shared the same wards, Rouse replied that:

I never saw them together but I always considered the hospital a place of rendezvous for men and women convicts. I have seen them romping together in the yard.[27]

In discussing the state of repair of the hospital, Rouse described that the original windows were glazed but they had to be repeatedly repaired until he decided to replace the panes in some parts of the windows with wooden squares. There were no shutters to the windows. On the question of repairs, he declared that repairs became useless after a time (the timber was so decayed). In reply as to whether Reverend Marsden ever discussed the ‘decayed state of the hospital and repairs with him’, Rouse could not recollect this but Governor Macquarie had given him directions on various occasions. When asked if the patients ‘were in a state of suffering and misery’ Rouse declared that ‘ it was so dirty and the smell so offensive that I could hardly go in’. When asked if the convicts complained, he replied that ‘the convicts would rather have done anything than go into the hospital, they have been carried there often against their will’.[28]

He was asked if he had seen any corpses lying in the hospital for the want of coffins to bury them, but he could not recall this. Another important question, coming from Marsden’s statement, was, ‘did he recall patients selling their rations for spirits?’. His reply was that he had seen patients lying about the hospital in liquor and ‘I imagine that it was by the sale of their rations’. When asked directly did he think that men and women used to resort to the hospital for the purposes of prostitution, he agreed stating that’ they got exempt from their work. The strongest and youngest of men and women were frequently (there)’.[29]

It is evident from these remarks that no one seems to have criticised the surgeons of that period, particularly Luttrell, for poor organisation within the hospital. In summing up, Commissioner Bigge reported:

The ruinous state of the old hospital and the deplorable consequences arriving from it described in the evidence of Mr Rouse, Mr Marsden and Mr West – orders given by Macquarie to Rouse for repairs were either not attended to or by him or were of little benefit on account of the decayed, rotten state of the building. Dead bodies were suffered to be in a passage that separated the male and female wards until coffins were found or prepared for them. Simple precautions of preventing intercourse between sexes appear to have been neglected – convicts of both sexes disposed by habit of licentiousness.[30]

THE PARRAMATTA COLONIAL HOSPITAL

The Parramatta Colonial Hospital, by Joseph Lycett, 1824 (Source: State Library of Victoria)

The Macquarie Hospital, 1815

Background

Because of the pressure on him by Marsden, Surgeon West and the Colonial Office concerning the state of repair of the old hospital, Macquarie determined it political to replace it. Lieutenant John Watts, his ADC and honorary architect, had already designed and built a new hospital for the military on Flagstaff Hill (Observatory Hill) in Sydney, picturesquely located on the ridge to the west of the Rocks, overlooking the harbour and the Parramatta River. As Watts’ first commission, the new hospital was quickly executed and was ‘virtually completed and partially occupied in July 1815’. [31] Morton Herman writes that it was an important building for Sydney as it followed the lines of similar army buildings in tropical countries. A single storey building for the accommodation of the surgeon and his assistant was added in 1821. It was an important building for Parramatta too as it became the model for the town’s new hospital.[32]

The Sydney building remains today as the core of the National Trust of Australia (NSW) headquarters. It is now shrouded by Victorian additions added by Mortimer Lewis when the site was given over as the first National Model School in 1849. It remained a co-educational school, known Fort Street until 1916 when the boys moved to a new school at Taverner’s Hill. The girls followed in 1974 and the complex was given to the National Trust.

It was inferred that Macquarie put his own self-interest in building the Government House at Parramatta ahead of the building of a new hospital. This of course is an esoteric question in many ways but Macquarie’s explanation to Commissioner Bigge for his reason:

Parramatta, before commencing the hospital there. I therefore think it proper that you inform yourself of the state of the only Government House that I found there. That [Government House] at Parramatta was in danger of falling, and without immediate repairs and attention it could not have stood.

He also commented that he thought that a person in his position should have a house to live in that was safe and commodious.[33]

Location and design

John Watts drew a plan and elevation for a new building and these are still available to us where unfortunately those of the Sydney hospital are only reconstructed measured drawings. The hospital was located facing the river, to the east of the second hospital and with access to Marsden Street, which Macquarie had extended from George Street. The site was approximately where Jeffery House stands today. Governor Macquarie approved the plans on 16 April 1817 building was commenced in August and completed by September 1818.[34] Macquarie’s description of the hospital read:

A hospital built of brick, two stories high with an upper and lower verandah all round with all the necessary out offices for the residents and occupation of 100 patients with ground for a garden and for the patients to take air and exercise in, the whole of the premises being enclosed with a high strong stockade. [35]

Both the Sydney Military Hospital and the Parramatta Convict Hospital designs were identical and were ‘standard barrack designs’ although Parramatta was to a different scale. Both were similar to the Sydney Rum Hospital that had a broad roof of about 50 feet with an almost continuous pitch extending from the ridge to the verandah columns. A shortage of appropriate timbers for large roof members gave way to two small roof structures with a central gully between. The roof of the Military Hospital at Sydney spanned 46 feet whereas at Parramatta, Watts reduced the span to 38 feet ‘making it probably the first large building constructed in the colony with a continuously pitched hipped roof sitting on verandah posts’.[36]

Symmetrical Georgian design was all important and sometimes function became secondary, so auxiliary buildings were grouped behind the hospital. At least at Parramatta, Watt introduced separate wards for each sex and included separate staircases in the women’s wards for access, to ensure privacy. Nevertheless, Commissioner Bigge was critical of the arrangements sensing promiscuity between patients, no doubt alerted by Marsden. Ground plans indicate that the outbuildings contain a ‘dead room’ or morgue, an overseers room, and a kitchen. Another building also is designated as a morgue but also make provision for a room for women and a wash -house. There are ‘privies’ for men and women amongst the outbuildings. Watts and Macquarie obviously made attempts to overcome the shortcomings of the previous hospitals.

Surgeon Major West, in his evidence to Commissioner Bigge, claimed that although he was the resident surgeon at Parramatta, he was not consulted by either the architect or the governor as to the design of the hospital. He claimed that with accommodation for 50 patients it was too small and indeed in the winter of 1819, he had to house 95 patients after an outbreak of a form of typhus.[37] West attributed this outbreak to the fact that convicts were living in huts that were not watertight with only earthen floors and resulted in the occupants being exposed to continual dampness. He further claimed that no provision had been made to completely separate males from female patients in the hospital and that water closets had not been installed in the building, nor was provision made for staff accommodation within the hospital.[38]

In 1817 Macquarie reported that the hospital was being erected by ‘convict artificers’ and so it can be said that the building was truly convict built. Watts’ work was overshadowed always by that of Greenway who practised during the same period. If he lacked Greenway’s artistic flair in his architecture, it would be safe to record that his hospital design, like his other buildings ‘showed good sense and a neat, competent command of design, which resulted in clear cut and unhesitant, and useful buildings’. Watts’ hospital at Parramatta served the town almost until the end of the century when it was demolished to make way for a new and larger building.[39]

Hospital conditions

West was apparently more aware of the benefits of good hygiene of the growing need for better hygiene in hospitals. He reported to Principal Surgeon D’Arcy Wentworth that patient’s ‘cleanliness of body and apparel’ on entering hospital were ‘ill calculated for bestowing attention’. His submission caused Earl Bathurst to approve in 1818 an issue to each male or female an entire change of clothing on admission to hospital. Wentworth also recommended that patients diets should be altered to include ‘fresh animal food [beef, pork, chicken or fish] and bread and vegetables be supplied daily by contractors.[40]

Wentworth resigned in October 1819 and was succeeded by James Bowman as Principal Surgeon. Bowman felt that because of the rise in convict population, a dramatic reorganisation of the hospital system was due and set about implementing the hospitals in ’a more regular and systematic manner’. He recommended the appointment of a second assistant surgeon at Parramatta without success but was able to provide a forage allowance to allow the surgeon to travel to outlying convict stations. Further, to overcome the poor supply of medicines, he initiated a supply calculated to maintain stocks for two years, thus ensuring a continuity of supply. Another successful initiative, advocated by West, and commencing in 1822, was in the payment of hospital attendants. Paid attendants included an overseer, a dispenser and a wards man and cost £39. 15. 0 annually.[41]

The diseases prevalent during the 1820s in Parramatta included inflammation of the eyes, which led to blindness unless treated, consumption and dropsy. Responsible for half the deaths of convicts in Parramatta was dysentery. An influenza epidemic in 1820 was fatal to many infants and the elderly, in 1824 it was mumps, and in March 1828, ‘hooping cough’ (sic). The latter disease affected the whole colony killing many children, including Governor Bourke’s son. Dr Anderson, who was responsible for the health of a convict stockade on the Cox’s River had to deal with a severe outbreak of scurvy there which he felt was partly due to ‘inattention to cleanliness, deficiency of clothing and a scarcity of blankets’. As no means of transportation to hospital was available, seventeen convicts died. Anderson reported the matter and as a result received approval for the use of a cart to transport patients to hospital.[42]

Governor Darling undertook many reforms in the hospital system including raising surgeon’s salaries and improving conditions. He also determined that settlers pay for the hospitalisation of convicts assigned to them, which was considered an unpopular move by settlers, many of whom refused to pay and so convicts were not reassigned to them. Darling started to close the smaller convict hospitals in the colony, a movement that gathered momentum once it was determined to cease transportation in 1840.[43]

Dr Patrick Hill, a compassionate medico, advised the Colonial Secretary that the hospital was faced on occasions with emergency cases, mainly from convicts who had served their sentences, but now were paupers and unable to support themselves. Hill found them suffering from ailments such as dropsy, general debility, broken limbs, old age and infirmity. Their numbers continued to grow during the 1840s and in 1844 for example, a total of 34 paupers were admitted to Parramatta Hospital. In January and February of 1845 alone there were 28 admitted. This prompted the governor to look at admissions carefully and comment that ‘it is distinctly understood that the government hospitals are maintained for the use of convicts and not for paupers. ‘Nevertheless, he felt that until the establishment of a hospital for paupers, supported by the contributions of the charitable, paupers would have to be admitted into the hospital, but such admissions would require written permission from the Colonial Secretary. This outlook foreshadowed the establishment of the Benevolent Asylum in Parramatta’.[44]

An alternative given to Dr Hill was that he could admit private patients at the cost of three shillings a day but the returns for the hospital did not show any voluntary ‘private’ patients being treated during 1841 at this inflated cost. In 1846, convict patients only allowed the use of the hospital unless an order was made by Local Government that was made responsible for the payment of one shilling and threepence per day for each patient. This was subsequently reduced to one shilling per day thatas regarded as being the average cost to maintain a patient at the Parramatta hospital. This included the cost of food, medical care, medication and clothing which, when costed out, amounted to only ninepence a day. These figures apparently costed in the ancillary staff which now included nine male and four female attendants, an overseer and a dispenser.[45]

The cessation of transportation to New South Wales

With the recommendation in 1840 of the Molesworth Committee in England to cease transportation, the head of the medical service in New South Wales, Dr Thomson, submitted his plans to the governor. He planned to close the hospital at Parramatta at the end of 1843 and treat future and existing patients at the Female Factory, a move that would save the government up to £2000 per annum. Dr Hill resisted the planned reorganisation stating to the governor that:

The Parramatta Hospital consists of four wards, three of which are appropriated for the reception of females and one for males. It contains fifty bedsteads the average number (of patients) daily during the years 1841 and 1842 has been above sixty and on some occasions amounting to seventy rendering it necessary to make up beds on the floor … while … the hospital at The Factory consists of three small apartments capable at the utmost of containing nineteen bedsteads… and is chiefly for midwifery cases.[46]

Dr Hill also thought that Dr Thomson had never visited the Female Factory and had only been to the Parramatta Hospital once, and was out of touch with the situation. Hill pointed out that there were 600 inmates at the Factory and felt that the medical arrangements there should be maintained. He raised the possibility of what would happen if a contagious disease broke out, and of course, what was going to be the fate of the male patients, the female assigned servants and the ticket of leave persons? Not wishing to oppose his Head of Department, the governor decided to leave the matter in abeyance. He must have been relieved when he was fortunately advised to remove Dr Thomson from his current office on the grounds of ‘neglect of duty’. He was replaced from England by Dr Dawson who saw Hill and his other doctors as highly professional and skilled in their duties. The governor reported in late 1844 that since Dawson’s arrival, the Medical department ‘had gone smoothly and well’. This harmony continued until the inevitable break up of the convict medical establishment and the subsequent closure of the Colonial Hospitals.

A Dr William Dawson arrived in February 1848 who had been appointed as the new head of the Medical Department. In 1847, the British Government had decided to place the remainder of the serving convicts in Van Diemen’s Land and the remaining doctors with them. The only exception was Dr Hill who was to remain in New South Wales as the Inspector and Consulting Physician to the Lunatic Asylum and Gaols and other colonial medical establishments and offices at a salary of £520 per annum. The Colonial Hospital at Parramatta closed on 31 March 1848 but opened the following day as the Parramatta District Hospital. These events are related in the history of Dr Mathew Anderson, (who was also the Warden of the Parramatta District Council) who aided by Dr Hill successfully negotiated on behalf of the citizens of Parramatta to have the hospital ceded to them. On 15 June, 1848, this transfer was ratified by the Legislative Council. The Parramatta Hospital entered a new phase of its history as the Parramatta District Hospital.[47]

THE PARRAMATTA DISTRICT HOSPITAL

Parramatta District Hospital, c.1940s (Source: City of Parramatta Council Local Studies Photograph Collection, LSP00157)

The Macquarie Hospital: 1848 – 1897

A public meeting was held on 28 March 1848, because of the rumours that were circulating that the hospital was to be handed over to the Benevolent Society. Gilbert Eliott , the Police Magistrate presided and it was moved by James Byrnes and carried that:

This meeting, having heard that the Colonial Hospital at Parramatta is about to be discontinued by the Government, it is resolved that a petition be presented to His Excellency the Governor [Sir Charles Fitzroy] praying for the use of the same for the inhabitants of this town and district.

At a public meeting on 6 May 1848 a favourable reply was read and the following members of the community were elected to manage the hospital – George Eliott Esq, Hannibal H. Macarthur Esq, Dr Mathew Anderson Esq, John Blaxland Esq, George Suttor Esq, Nelson Lawson Esq (pastoralists), Messrs James Edrop (pastoralist), James Houison (architect and businessman), James Byrnes (flour miller and businessman), George Oakes (pastoralist), John Hamilton (flour miller), M. McKay (publican) and Solomon Phillips (storekeeper). These names were submitted to the governor and accepted. It has been commented upon that it was hoped that the governor was not too upset over the ratio of six gentlemen to seven others. The governor on the recommendation of Police Magistrate Eliot appointed many of the same gentlemen, on the formation of the District Council. Like that committee in its first year, many of the gentlemen lost interest in the hospital and attended irregularly and as a result, were not elected during the following year. Dr Anderson was appointed the President, James Houison Treasurer and Solomon Phillips, Secretary. A further meeting held in August 1848 appointed Nelson Lawson Esq, Nathaniel Payten (stonemason and businessman), George Oakes, George Suttor Esq and Gilbert Eliot as Trustees and James Houison as treasurer to the trustees..[48]

The Parramatta Benevolent Society, founded in March 1838 had as its object ‘affording relief to the poor and distressed’ and therefore ‘discouraging vagrancy and ‘to encourage industrious habits amongst the indigent’. During the 1850s, the Society used the upper floor of the hospital for the relief of female paupers. This was income for the establishing hospital but the committee from time to time resisted suggestions that the two organisations should combine. The medical staff clearly saw their objective as a hospital and not as aged care establishment.[49]

The first committee meeting invited Drs Hill and Robertson to superintend the hospital and they accepted. An advertisement was placed for a matron and Henry Williams and his wife were appointed as overseer and matron at £17.10shgs per annum and their board. During 1848 a cook and general servant (John McDermot), a nurse and washerwoman (Margaret Farquhar) were appointed at £12 per annum each. A wards man (McLeavy) was paid annually at the rate of £3. 4shgs and keep but hi wages were increased to ten shillings a month and an allowance of two shillings for shaving the patients.[50]

The year 1873 saw the introduction of gas for lighting and heating when the Parramatta Gas Company began connecting mains throughout the town. For some reason, probably financial, the Committee decided against lighting the hospital but altered its decision in 1879. In December 1876, tenders were called for two bathrooms, one for each sex together with a force pump to supply water to them. New fencing was built and flower gardens were laid out. Drs R Bowman and Isaac Waugh joined the staff in 1874. [51]

The vocation of nursing was a lowly paid, lowly regarded one where nurses, mostly women, had no training, little wages and were regarded as little better than general housemaids. With the advances in and complexities of medicine however, the need for skilled assistants arose who could interpret the necessity for cleanliness and orderliness and undertake the routine daily medical instructions required by the medical staff. The first training school for nurses commenced at Sydney Hospital in 1868, eight years after Florence Nightingale began training nurses at St Thomas’s Hospital London. Lucy Osborn and five trained nursing sisters arrived in Sydney in March 1868 at the invitation of Premier Sir Henry Parkes where Lucy Osborn was appointed as Superintendent. The first Nightingale trained nurse to be appointed matron at Parramatta was a Mrs Pearson who commenced duty on I March 1876 at a monthly salary of £6. 5. 0 and board. In 1877 she was given the authority to suspend any employee under her charge and was appointed Hospital Superintendent.[52]

In 1880, there was a strong reminder by the medical staff to the Committee for the provision of a separate room, promised a year ago, in which to perform operations, detailing an amputation case for which they had to use the table:

The patients dine at, which is not an agreeable sight when stains of blood are left on it and the loss of blood staining the floor and clothes is a sickening sight.

They also requested the committee to pressure the government for a place to nurse ‘infectious and contagious persons’.[53]

The first operating theatre, 1882

Some years earlier, the committee had made overtures to the government to have the hospital land dedicated but this was not gazetted until 11 March 1881. In 1882, the committee began moves to have water reticulated from the Hunt’s Creek Dam, connected to the hospital. No mention is made of the fact that that it was Dr Mathew Anderson, their first President, who was responsible with two other Trustees, James Houison and Nathaniel Payten, for the erection of the dam in 1850-51. It had taken 30 years for the water supply to be piped to the town! In the same year, 1882, it was reported that the operating theatre was almost ready for use. In the following year, funds even allowed for an ice chest. In January 1883, Drs brown and Waugh retired as honorary doctors.[54]

A dispensary opened, 1884

A separate dispensary was set-up for the first time in 1884 under the care of the matron, who was now called the superintendent and responsible for much of the administration of the hospital. On 5 March 1884 the medical -officers were asked by the committee for their views on the building of a new hospital and they were in favour. Typhoid cases were increasing (64 during the year) and the need for a separate infectious area had become urgent. In 1885, with the building of Prospect Reservoir close by, it was found that many of the 271 treated for the disease were from the makeshift town nearby (Prospect). This work force caused extra medical problems and the Committee asked the government in 1886 for a special grant of £500 towards dealing with the extra demands on the hospital. The grant was eventually granted but the typhoid was only slow in diminishing in numbers and was still prevalent in 1887. The government’s answer to the need for an infectious diseases building was to suggest that that the hospital staff deal with the Prospect patients at Prospect, in their own homes. In January 1889, Dr WS Brown was appointed to the staff.[55]

A hospital secretary appointed, 1888

As extra funds became available from a bequest, it was decided in 1888 to appoint a secretary to care for the daily administration and thus allow the matron to supervise the internal management of the hospital, the nurses and other hospital staff. The year 1892 saw the gardens being refurbished and the gardener’s shed renovated and refurbished for the use as an infectious diseases ward. The government made a special grant of £130 towards this end. A hospital ball raised £75 and this was used towards the provision of a dining room. Gas heating was installed in 1894 and a boiler which allowed provided running hot water. Typhoid was still prevalent in 1895.[56]

The 1890s saw stringent economies throughout the hospital due to the financial depression of the times. In 1892 Matron Greenwood reduced the dispensary drug bill considerably and was highly praised in the Annual Report. In the 1896 Annual Report by the committee, Chairman JA Oakes, reported that in conjunction with Messrs Sulman and Powers, architects, plans had been drawn up for a new hospital at an estimated cost of £4000. The Hospital Committee was hopeful in having the building opened in 1898 to celebrate the jubilee of the 1798 hospital. [57]

During 1896 Nurse Rutter was appointed Matron and brought the profession into great respect through her managerial and medical skills. When in 1906, she was praised for the thoroughness of her work, the Board of Directors recorded that the doctors regarded her as equal in ability to a resident surgeon. Matron Rutter retired after 16 years in the position.[58]

It is assumed that the old hospital was not removed until the Cottage Hospital, which was built in two stages, was not demolished until 1898-9 when the new hospital was completed and occupied. In August 1901 the old stables, old cottage [doctor’s residence?] and the smoking shed, the remains of the 1815 hospital, were removed, ending another era.[59]

The Cottage Hospital: 1897-1943

On 24 January 1896 Viscount Hampden, Governor of NSW, laid the foundation stone of the first section of the new building. Finished by December of that year, the cost was approximately £1200 and comprised two new wards and an infectious ward and was occupied in January 1897. It was necessary to maintain the 1815 hospital until the new building was completed, which require time and funding. £1500 was required to complete the hospital. The AGM reported that they hoped to complete the remaining work by 1898 and that they were hoping to receive £3000 subsidy from the government and the government were willing to discuss the matter. In 1899 the Premier visited the hospital and promised funding, reporting in 1900 that £2000 had been placed on the estimates. On the strength of this, the Committee proceeded with the building programme.[60]

A contract was let with AE Gould for £3075. 19. 3 for completion in seven months. Accordingly, the old buildings were pulled down to make room for the new and the Foundation Stone of the new block was laid. In 1902 it was announced that the new building had been complete, free of debt but that money would be required for maintenance.

The hospital

The red brick hospital was located to the west of the old hospital, facing the river, in a composition of three blocks built in the Federation Queen Anne Style. The central block was two storeyed with a hipped roof of Marseilles pattern terracotta tiles, on the ridge-line were two massive chimney each with six terracotta chimney pots. The block was three bayed, louvres to the upper windows and on each side which were spaciously verandahed. The verandah columns were of timber with simple timber capitals. The front entrance was emphasised by a semi circular arch on slightly larger verandah columns which were paired with the nearby columns. The verandahs ran down the side of the building to meet the cross corridor of the single storeyed buildings which led to the gabled pavilions on either side. All of the buildings were connected by the verandahs that gave hospital a domestic or ‘cottage’ appearance. Tall Federation chimneys in white spatterdash were located on the corridor buildings. The minutes recorded the following description:

A hospital up-to-date in every respect… large and commodious wards (male and female surgical, male and female (medical) – an infectious ward – private wards – an excellent operating theatre – also a splendid administrative block, well furnished throughout. The grounds and operating theatre are not yet in order and it will remain for the incoming committee to add the finishing touches, such a laying out the grounds and making a more suitable entrance[61].

New kitchen facilities, 1900

While the new building was in the making, a new kitchen range with a built in boiler and a new hot water system was installed. During June 1902 the grounds between the hospital and the river were being laid out and a 1906 photograph of the front of the building shows a circular driveway and lawns.[62]

Introduction of X- Ray equipment and sewerage connected, 1910

During 1905 X ray equipment was purchased and in 1910, a government grant of £532 allowed the sewerage to be connected. Electrification was installed and turned on in March 1914 and during that year, a government allocation of £1500 was made towards a new nurses quarters. During the war years several of the medical staff applied for leave to join the Army Medical Corps. By 1915, with the continued population growth of the district, the hospital beds could not cope with admissions. Whilst the government talked of a new district hospital, the Board widened verandahs and, made them into wards, permanently in- filling some of them. A new nurse’s quarters was planned with a grant of £1500. 1919 saw an influenza epidemic but the hospital could only allocate ten beds for such patients, suggesting that the overflow be directed to Lidcombe State Hospital.[63]

Nurse’s accommodation, 1923 and 1924

Brislington had been rented from the Brown family for temporary additional nurses accommodation but more accommodation was required. Plans were made in 1923 with the Public Works architect to build two storeyed accommodation for 28 nurses. Designed with verandahs twelve feet wide, it included a dining room, sitting room, kitchen, toilets and bathrooms. The estimated cost was £13500 but in 1924 a quote for £9050 (final cost £9177.17.2) was accepted, a third of which the government was prepared to advance. These quarters were located to the west of the hospital.[64]

It was clear that the hospital, only 28 years old, required enlarging and the succeeding years saw numerous alterations and additions. In 1926 a casualty room, a staff dining room and accommodation for the matron and the resident medical officers. Were added while there was need for a new laundry, a children’s ward, domestic quarters, a waiting room for out-door patients and a laboratory, all estimated to cost about £6,000. The government reply was favourable to the request to place the amount on the estimates. In 1925 the nurses home was opened by Dr Kearney and in 1926, £1500 was received from the Fairfield Committee towards the cost of the Children’s Ward, approval for which was given by the government in early 1927, and this building became the focus of the Boards attention but had to be delayed because of coming economic events[65].

A children’s ward, 1934

The 1930s saw the depression years resulting in curtailing of costs, building, wages and salary cuts. Notwithstanding, requests came to the Board for a new maternity wing and additional work in the out patients department. By 1933, the building of the children’s ward had begun and was completed by the end of 1934. Unfortunately it could not be opened until housing was built for the additional nurses required to staff the ward that planned for seventeen beds. This was all accomplished by January 1935 when the children’s ward was opened by the Minister of Health. By this time, on the staff, were fourteen honorary medical officers, seven honorary consulting surgeons, five honorary dental surgeons and one honorary consulting dermatologist. A new X-Ray building was complete by 1936.

Jeffery House: 1938-1943

In 1937, the Board recommended to the Hospitals Commission that a new hospital was needed and plans were prepared. The problem was that the community would have to raise half the finance of the estimated cost of £60,000. By the end of 1938, plans were revealed to erect a four storey building to accommodate 140 patients and it was hoped to begin as soon as the Health Commission agreed; the Board became exasperated when this approval was continually delayed.[66]

Effects of World War II, 1938-1945

As the war spread, many of the medical and nursing staff were drafted. The foundation stone of the new hospital was laid on 10 October 1941 by Lord Wakehurst the governor. Construction, by the Public Works Department, was slow because of a brick strike which paralysed supply and allowed many bricklayers engaged on the job to be absorbed into other defence projects, delays and difficulties in the delivery of sand, cement, bricks and metal due to petrol restrictions and difficulties by the contractor to maintain a working force because of call ups. The contractor was not held to fault. During 1943 Dr JAH Jeffery was appointed Senior Resident Medical Officer but was later called up for war service. The Board agreed with the Government Architect’s plan to recondition the old hospital building for administrative purposes while in July, some male patients were transferred to the new building. Doctor Leslie PH Jeffery was appointed the first Medical Superintendent during September who announced that supplies of the new drug penicillin were now available for hospital use. The new block, as yet unnamed was officially opened by the Minister for Health, Hon CA Kelly on 5 November 1943.[67]

Jeffery House: 1944 – 1990s

Jeffery House, c. 1970s (Source: City of Parramatta Council Cultural Collections, ACC002/40)

Although officially opened, the new hospital block could not be used due to a lack of nursing staff and funds to furnish the wards. In January 1944, the new operating theatre was opened. By April new equipment had been received but there was a lack of staff due to ongoing call ups for war duties. At the AGM it was reported that the cost of the new building had risen to £105,000 and was not yet fully functional because of staff shortages. There were 105 beds in use and 52 waiting to be used as soon as accommodation could be found for the additional 24 nurses and 4 sisters required.[68]

In early 1945 the Board began discussing with the Hospitals Commission the necessity for a maternity block and the Minister for Health gave assurances that a new block to house 80 to 100 beds would be built. The board now wanted a master plan prepared to incorporate a main hospital of 350 beds, a children’s ward of 40 beds, a convalescent home, a maternity block of 100 beds as well as ancillary ante and post natal units and an outpatients department. They also asked that additional land be resumed.[69]

Nurse’s conditions and appointments, married and male nurses, 1940-1953

During the war years, married nurses were welcomed to the staff because of shortages. A Mr Shaw applied for the position of male nurse in 1945, the first recorded in the hospital minutes. This was approved and it was determined that he had to pass the usual nursing examinations. In 1946, nurse’s hours were reduced to 40 per week, and, by 1967, it was decided that nurses were no longer required to ‘live-in’. This was of mutual benefit to the administration and to the nurses.[70]

In 1946 Dr Richard Phipps Waugh resigned from the staff after 41 years service as an Honorary Medical Officer and sometime President of the Board; his father, Dr Isaac Waugh had joined the hospital in 1874 and served until his death in 1911. (Dr R. P. Waugh died in April 1948). This record was only surpassed by the three generations of the Drs. Brown of Brislington. In 1946, approval was given by the Hospitals Commission for the Board to acquire required property for extensions.[71] By August 1946, 114 beds were in use and because of constant interruptions to the electricity supply during 1948 (due to lack of coal caused by striking miners),the hospital was required to purchase emergency lighting plant. Following upon the resignation of Dr L. Jeffrey as Medical Superintendent to return to private practice, Dr. Dorothy Conchae (later Lady Macarthur Onslow) was appointed in his stead. At the AGM in 1948, the Chairman, Mr Jeffrey commented that there was now sufficient staff to allow 126 beds to be used and that the Board had continued to urge the Minister to implement the promise of a new hospital but it was evident by 1949 that here was no possibility of a new hospital or another two or three years. However, negotiations were still pursued for a new maternity hospital.[72]

New maternity ward, 1955

The new hospital planned was estimated to cost £2 million and, considering the expanded population of the district, would require some 700 beds. The Minister, despite advising that funds had been set aside to convert the top floor of the new block of Jeffery House as a maternity ward, promised a prefabricated maternity hospital and in 1954 tenders were accepted for the erection a of a new nurses home and maternity unit for £79,442. By August work was under way and the first baby was born in the unit in November 1954; the unit was officially opened by Hon GC Gollan, Minister for Health (and local member) in November 1955. It had taken eight years to become a reality.

The Board still insisted that another 400 beds were still required. In 1955, the Commission offered £10,000 towards the cost of a newout patients department. In November 1955 the pre-fabricated Maternity Unit was opened by the Premier, JJ Cahill.[73] The unit cost £150.000 and equipment and furniture another £30000. In September 1956, Mr PH Jeffery, who had been chairman of the board for 26 years, did not seek re-election. In April 1957, the Board resolved to call the main building Jeffery House after the loyal and untiring service of PH Jeffery. In December, the Board had to re-open the temporary maternity services in Jeffery House due to increased demand.[74]

It was proposed in early 1968 that the hospital seek affiliation with Sydney University that would enable the hospital to provide some degree of teaching facilities, and the University responded positively. The Secretary, now designated the Chief Executive Officer, was investigating computer systems. A public meeting was held at the Parramatta Town Hall on 1 July 1968 that passed a resolution:

This meeting deplores the inhuman activity of the Government of NSW in the past 25 years in regard to the provision of adequate public hospital facilities for decent and proper attention to the needs of over a quarter of a million long suffering but apparently forgotten people, requests that the government honour the promises by the Minister and an immediate start be made on a new hospital on the present site.

The new hospital for Parramatta

Mr Jago, the Minister for Health, attended the August Board meeting and announced that:

(1) the building of a major teaching hospital for the University of Sydney on a site of about 100 acres at Westmead. It was to be of 800-1000 beds and would cost approximately 40-50 million dollars. (2) The ultimate closing down of Sydney Hospital on its present site. (3) The ultimate closing down of Parramatta Hospital on its present site. He stated further that the work would take eight to ten years to complete.

The Board expressed their agreement and resolved that a list of certain facilities be drawn up to serve the hospital during the immediate period. The National Trust advised that they had classified Brislington; they opposed its demolition and recommended restoration, as a result the Commission granted money for urgent roof repairs and painting of £7500 by Public Works department..[75]

With the interim period waiting for a new hospital, which was estimated to be available in 1976, action was taken in 1969 to add another storey to Jeffery House and enclose the verandahs of the old hospital. With other minor works, the estimates were £931, 000 which the Commission agreed to fund.

A swimming pool for the nurses was opened in March 1971 and this was heated in the following year. In 1972 the University of Sydney granted status as a teaching hospital to Parramatta. Stage 1 of the additional floor to Jeffery was begun, adding fifty two beds and the 30 beds to the children’s ward Available beds now numbered 270 and the staff numbers had risen by 100 to 646. Brislington was to be fully restored in 1973 at a cost of approximately $22,000 and it was proposed that it be converted to a kiosk. National Trust however was hoping that it may be converted for the use as a museum. In April 1975 $400, 000 was received for further work on Brislington and the City Council received $100,000 to beautify the corner. [76]

The Health Commission came into being as an amalgamation of the Hospital Commission and the Department of Public Health in April 1973. Parramatta fell into the Western Metropolitan Region and recognised as a ‘health scarcity area’. The Minister gave assurances that the Parramatta Hospital would not close with the opening of Westmead. It was decided in early 1976 to establish a coronary care unit which was later followed by a cardiac rehabilitation unit. A visit by Dr GR Andrews, the Regional Director of Health, was made to discuss with the Board’s fears of a possible closing of the hospital with Westmead’s opening. A new medical library was established. By April, the construction of the Accident and Emergency Centre was completed – a portent of things to happen!..[77]

The Granville train disaster

On 18 January 1977, Australia’s worst train disaster occurred at Granville when a carriage from an early morning train from the west struck a support of the Bold Street overhead traffic bridge. As a result, 83 people died and 34 were hospitalised at the Parramatta District Hospital. A letter was sent from the Health commission:

Thanking the medical teams for the way in which they responded and also individual staff members for the high degree of dedication displayed. In March a letter was received from the Minister of Health the Hon Kevin Stewart who expressed ‘ very sincere and deep gratitude to all the medical and nursing staff involved with the tragic accident at Granville, especially those personnel on the site because the conditions under which they worked with such skill at grave risk to their own personal safety’.[78]

In April, the Commissioner for Personal Health Services, Dr Andrews, addressed the Board on the future role of the Parramatta Hospital. He stressed that there would be no reduction of services to the people of Parramatta and that the hospital’s role would be to complement that of Westmead’s role. By November 1977, 299 beds were available. The hospital was given full accreditation by the Australian Council of Hospital Standards for three years. In October, the Medical Education Centre was opened for Sydney University students in Community Medicine were able to attend lectures. Westmead was progressing to schedule and Dr BJ Amos had been appointed as Chief Executive Officer.[79]

The Westmead Hospital

Westmead Hospital under construction, c. 1977 (Source: City of Parramatta Cultural Collections, ACC002/61)

The Minister for Health, Mr Stewart announced in February 1978 that Parramatta would be fully integrated with Westmead Hospital and that the Board of Directors would comprise three from the Parramatta Board, three from Sydney University and six from the general public. It was planned to continue Parramatta as an acute general hospital for at least five years and keep all facilities operating. It was announced that the name of the integrated hospitals was to be the Parramatta Hospitals. On 4 October 1978 the last Board meeting of the Parramatta District Hospital met and was reconstituted on 6 October as the Board of Directors, the Parramatta Hospitals. At this time, the Parramatta Hospital had 314 beds available, a staff of 908 and had expended over $112 million during the previous year.

Westmead Hospital accepted its first patient on 1 November 1978, beginning a new era in health care for the people of Western Metropolitan Sydney.[80] On 10 November, the Premier of NSW, Neville Wran QC, officially opened the hospital.

John McClymont, Parramatta Historian, 1999, published Parramatta City Council Heritage and Visitor Information Centre, 2018