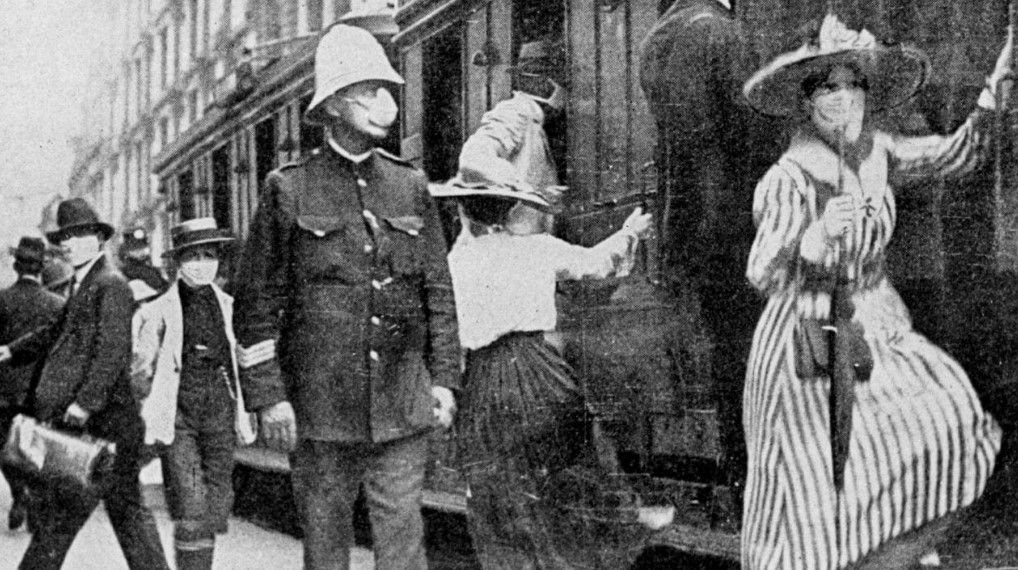

Commuters in Sydney wearing masks during the influenza pandemic, 1919. Image: The Australian

A global pandemic reaches Australia

In November 1918, as peace was declared and the guns of the First World War fell silent, people across the world began to succumb in great numbers to a deadly disease. Caused by a particularly virulent strain of pneumonic influenza, the illness was notable for taking the lives of an unusually high number of otherwise young and healthy people.

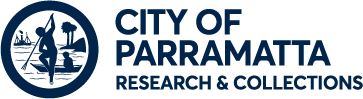

Commonly known as the Spanish ‘flu’, the disease is now thought to have originated in Kansas, USA, and been transported by American troops heading to the European theatres of war. [1] The uncensored press in Spain, neutral in the war, was merely the first to report large-scale fatalities.[2] During 1918/19 it is estimated approximately one third of the world’s population became infected with the virus. An astonishing 50 to 100 million lives are now thought to have been lost during the pandemic – well in excess of the 17 million lives lost to the First World War.[3]

Soldiers who contracted in the first wave of the “Spanish ‘flu” at Camp Funston, Kansas, 1918. Image: US National Archives, Otis Archives

The pandemic reached Australia in early 1919, and became one of the greatest public health disasters in the history of our country.

Parramatta was not immune to the deadly spread of the disease.[4] Buried within the cultural collections and historic archives held across the Parramatta area is unique material that identifies when the disease reached our neighbourhoods, and tells us how our communities prepared for, experienced and recovered from the pandemic.

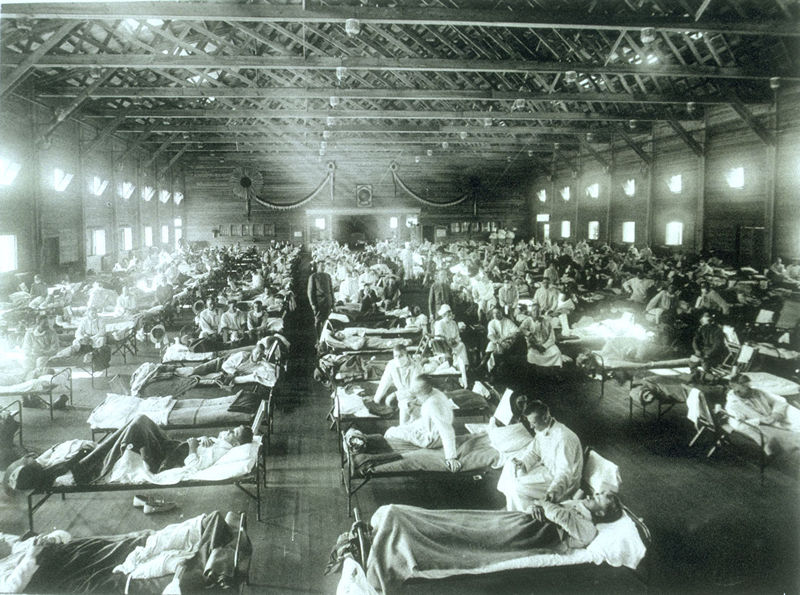

One fascinating archive record is a diary held by the Royal NSW Lancers Memorial Museum in which a young ‘Parramatta Lancer’, Trooper William Barracluff, expresses his frustration and anger when, after diligently counting down the weeks and miles travelling home on the SS Port Hacking, he learns on docking in Melbourne that he will be transferred immediately to quarantine. Trooper Barracluff writes:

Jan 19th Sunday: 248 miles. Airing uniform – last Sunday on board. Jan 20th Monday: 250 miles. Jan 21st Tuesday 241 miles. Jan 22nd Wednesday: Last inspection and pay. Entered Port Phillip at 8.30pm, dropped anchor off Quarantine Station. Jan 23rd Thursday: Placed in Quarantine. Are clean ship, have been inoculated and disinfected… but put in Quarantine, of course we have not been away long enough yet. Trouble brewing among the boys and they have every reason for playing up. Jan 24th Friday: Should have been home today. [5]

Diary of Trooper Barracluff, Parramatta Lancer, quarantined on return to Australia from WW1, January 1919. Source: Royal NSW Lancers Memorial Museum, 2014-001

The end of the First World War saw the mobilisation of people across the world on a scale never before experienced. Trooper Barracluff was only one of many who, returning to Australia from the battlefields of Europe and North Africa, were held first in the close confines of military camps and then on transport ships “looking forward to a triumphal return home and grand reunion with family and friends they had not seen for years”, only to be “bitterly disappointed”.[6]

Machine Gun Section, 1st Australian Light Horse Regiment, New South Wales, including Trooper W Barracluff – quarantined on return to Sydney in 1919. Image: Australian War Memorial, ref. P01208.019

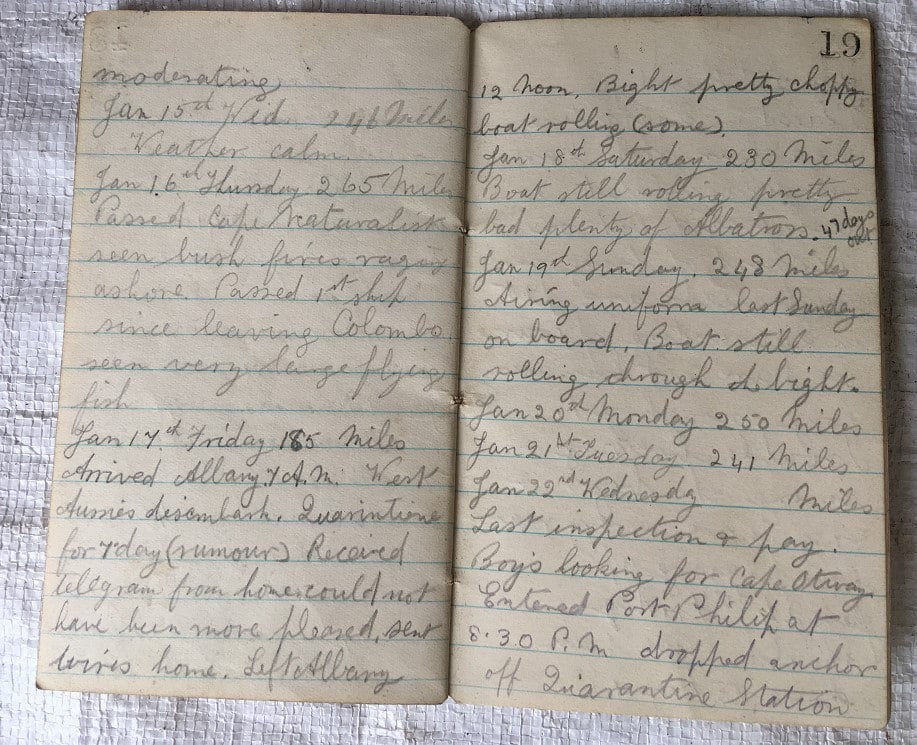

The understandable disappointment of the troops in quarantine was counter-balanced by the real need to protect the civilian Australian population from the pandemic. Many Australian troops had certainly contracted the disease abroad, some perishing even before their journey home began. Once such tragic case was Driver Richard Moxham, from a well-known family in Granville, who lost his battle with pneumonic influenza in France on 11 November 1918, Armistice Day, at the age of 20.

Driver Moxham lost his battle with pneumonic influenza on Armistice Day. Source: Cumberland and Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 7 December1918, p.10

Australia’s strict maritime quarantine rules successfully protected our population from the first two deadly waves of the disease. However, it was only a matter of time before the pandemic breached the country’s coastal defences.[7]

In early January 1919, cases of pneumonic influenza were diagnosed in Melbourne, and then in Sydney.[8] Despite the implementation of containment strategies across the state, cases were shortly afterwards diagnosed at other sites in New South Wales.[9]

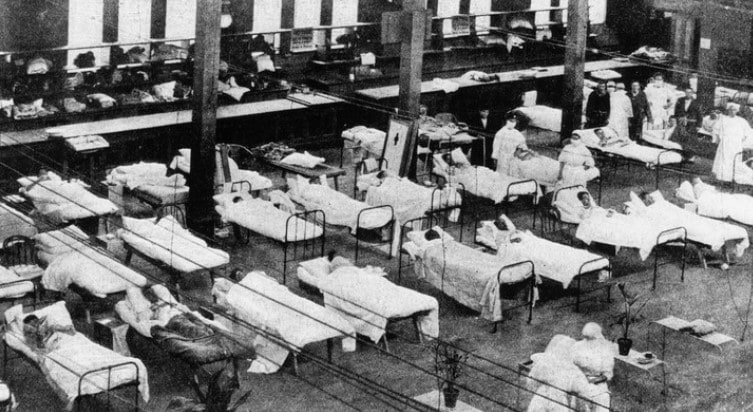

A makeshift hospital at the Royal Exhibition building in Melbourne for pneumonic influenza patients, 1919. Image: Heritage Council of Victoria

With the pandemic now confirmed as having reached Australia, the New South Wales State Government issued a series of proclamations in January 1919, restricting public movement. The proclamations directed the closure of all “libraries, schools, churches, theatres, public halls, and places of indoor resort for public entertainment”.[10] Use of public transport was discouraged, and it became compulsory to wear masks in public.

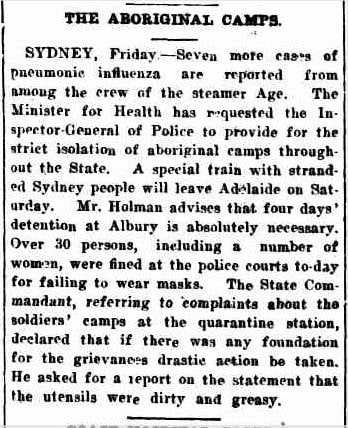

Official containment policies affected not only city dwellers but, as the disease spread through the state, also regional and rural populations. Aboriginal communities were particularly affected. Notification of an infected individual resulted in entire communities being transferred into regional ‘quarantine camps’, where their movements were rigorously patrolled by police under the instruction of the Department of Health.[11]

The enforced containment had a toxic outcome and in some Indigenous communities, pneumonic influenza mortality rates approached fifty percent (by comparison, non-Indigenous death rates were three deaths per thousand).[12]

Entire Aboriginal communities from across NSW were transferred to isolation camps during the pneumonic influenza outbreak. Source: Northern Star (Lismore), 1 March 1919. p.4

Despite best efforts to contain the disease locally, not long after pneumonic influenza had arrived in Sydney, the deadly virus crept into the neighbourhoods of Parramatta.

Pandemic in Parramatta: The Influenza Outbreak of 1919 (Part 2) explores the local Municipal and community preparations for, and responses to, the pandemic…

Michelle Goodman, Council Archivist, 2019

References:

[1] https://www.abc.net.au/news/health/2018-04-13/flu-pandemic-1918-what-happened-and-could-it-happen-again/9601986, accessed 26/2/2019

[2] Mamelund, S. (2017). Profiling a Pandemic: Who were the Victims of the Spanish Flu? Natural History, Vol.125(7), p.6(4), p. 6

[3] McCracken, K and Curson, P. (2006). An Australian perspective of the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic. NSW Public Health Bulletin. Vol 17, No. 7-8, p. 103

[4] McCracken, K and Curson, P. (2006). An Australian perspective of the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic. NSW Public Health Bulletin. Vol 17, No. 7-8, p. 103

[5] Trooper W B Barracluff diary. Royal NSW Lancers Memorial Museum, ref. 2014-001

[6] Troops stuck in quarantine (2017), 30 September). Manly Daily

[7] Armstrong, S. (1980) The pneumonic influenza epidemic of 1919. New South Wales. Student Research Papers in Australian History, No. 5. The Department of History, University of Newcastle. p.14

[8] Influenza in Sydney (1919, 28 January). Sydney Morning Herald

[9] Armstrong, S. (1980) The pneumonic influenza epidemic of 1919. New South Wales. Student Research Papers in Australian History, No. 5. The Department of History, University of Newcastle. p.15

[10] New South Wales Government Gazette, No.13, 28 January 1919

[11] Armstrong, S. (1980) The pneumonic influenza epidemic of 1919. New South Wales. Student Research Papers in Australian History, No. 5. The Department of History, University of Newcastle. p.16

[12] The Aboriginal Camps (1919, 1 March). The Northern Star (Lismore). p.4

[13] McCracken, K and Curson, P. (2006). An Australian perspective of the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic. NSW Public Health Bulletin. Vol 17, No. 7-8, p. 105