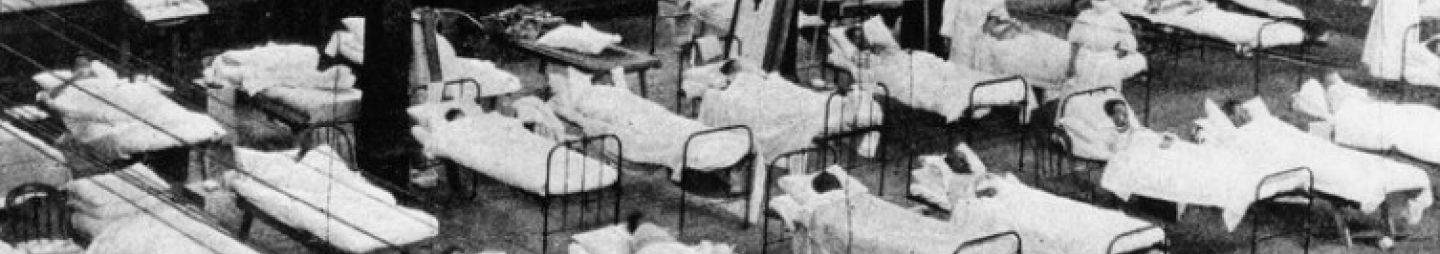

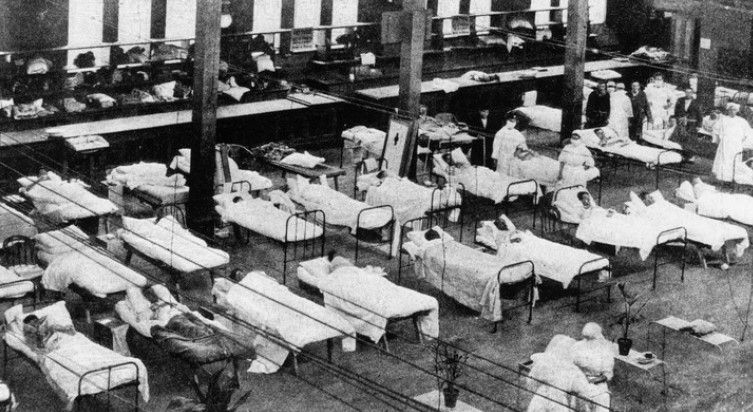

Makeshift Pneumonic Influenza hospital, Melbourne, 1919. Image: Heritage Council of Victoria

Parramatta prepares, and the pandemic arrives

In January 1919, cases of the deadly pneumonic influenza pandemic sweeping the world were diagnosed in Australia, first in Melbourne and then in Sydney.

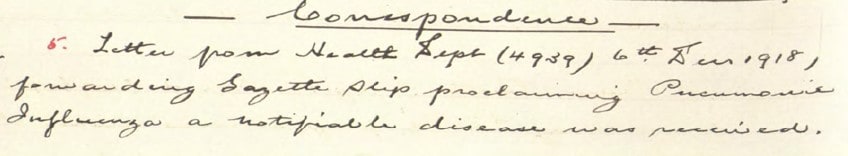

Pneumonic influenza identified as a notifiable disease, by order of the Health Department. Source: Minutes of the Meeting of Parramatta Municipal Council, 13 January 1919

Formal notification of the pandemic had first reached Parramatta in December 1918 by receipt of a letter from the Health Department of New South Wales proclaiming pneumonic influenza as a ‘notifiable disease”. Local governments were instructed to report immediately any suspected cases within their districts.[1]

By early 1919 Civic leaders in the Municipality of Parramatta, and the neighbouring Councils of Granville, Dundas and Ermington & Rydalmere had mobilsed into action to prepare for the pandemic. The Councils established Influenza Committees, and appointed Influenza Administrators to co-ordinate local responses to containment, treatment and relief.[2] .

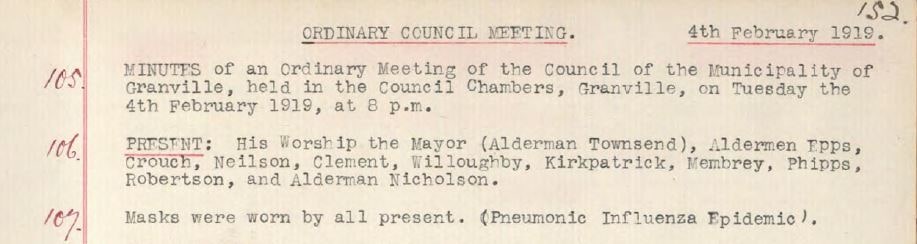

Despite potential health risks to Aldermen, Council Meetings continued to be convened, with masks worn during procedings.[3] Councils gave measured consideration to the potential social disruption that may be caused by a severe influenza outbreak. In Parramatta, the official Patrolman wrote to Council asking for guidance “should pneumonic plague break out in the District”, leading to panic and disorder.[4]

Masks were worn by Aldermen to Council meetings during the pnuemonic influenza pandemic. Source: Minutes of the Meeting of Granville Municiple Council, 4 February 1919

Strict restrictions on personal movement were introduced by the Councils with local businesses, schools, hotels, cinemas, dance halls and churches closed down. On 10 February 1919, Parramatta Municipal Council passed a resolution:

That in order to help combat the dreadful disease which has been devastating most of the countries throughout the world and to assist the State Government in its endeavour to check the possibilities of contagion by preventing as far as possible the contagion of too many persons in a small area, instructions be issued forthwith for the closing of the Centennial Baths until such time as all danger therein is passed and matters are from the country’s health point of view, again normal. [5]

Entertainment venues across Parramatta including cinemas, closed their doors during the pneumonic influenza pandemic of 1919. Image: City of Parramatta Local Studies Photograph Collection, LSP0856

As the weeks went by, with fear of the pandemic growing within the barracaded Parramatta communities and the streets and public spaces becoming increasingly and eerily deserted, Civic and community leaders continued to meet and plan behind closed doors. Municipal campaigns for infection containment and sanitation were launched, with property owners issued formal directives from Council to “maintain absolute cleanliness” and use disinfectant “liberally and wherever necessary”.[6]

An Influenza Pandemic directive from Council to property owners. Source: Parramatta Municipal Council correspondence files, 22 February 1919

Ultimately, concerted Civic efforts were not able to prevent the inexorable march of pneumonic influenza into Parramatta, and by March 1919 the local area was in the grip of a full-scale outbreak. As the pandemic took hold, the Mayor of Parramatta approved 100 pounds of Municipal funding, an enormous sum at the time, for the undertaking of containment and relief.[7] At the same meeting, the Mayor also put his official car at the disposal of those “working for the public interest” in fighting the spread of the illness.[8]

On 16 April, Dundas Municipal Council approved the installation of a telephone, a new technology in the district, at Dundas Town Hall, to co-ordinate the provision of influenza services.[9]

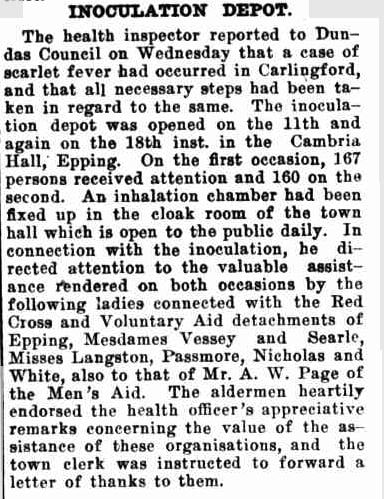

Beyond remaining indoors and observing hygiene and infection control recommendations, the residents of Parramatta had few other means of avoiding infection. Experimental influenza vaccines started to be distributed by the Australian Commonwealth Serum Laboratories. However, the exact nature of viruses were unknown, and effective influenza vaccines would not be available until the 1940s. An inoculation depot for the Parramatta area was set up at the Cambria Hall in Epping, where long queues formed for the vaccines.

An Inoculation Depot at Cambria Hall in Epping administered vaccines during the pneumonic influenza outbreak. Source: Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 22 Feb 1919, p. 8

Inhalation chambers, thought to ‘steam clean’ the lungs and therefore reduce the risk of pneumonic influenza infection were installed in the cloakrooms of the Granville, Dundas and Parramatta Town Halls and “open to the public daily”.[12]

Privately operated “inhalatoriums” were also installed by local businesses, including in the furniture show room of the landmark Murray Bros department store on Church Street, Parramatta.[13] Local pharmaceutical dispensaries also offered for sale a variety of supposedly miraculous influenza “wonder cures”.

Murray Brothers department store in Parramatta, where an ‘inhalatorium’ was installed during the 1919 influenza pandemic. Image: City of Parramarra Council Local Studies Photograph Collection, LSP00269

Retrospectively, the effectiveness of the inhalation chambers and over-the-counter remedies came to be dismissed as of little benefit beyond a potential ‘psychological boost’.[14] The effectiveness of the vaccines is contested, although it is believed they did provide some protection from the deadly secondary infections associated with the virus.[15]

As 1919 progressed, people across Parramatta continued to succumb to pneumonic influenza. Higher rates of infection and death were experienced in Parramatta’s poorer communities. A Parliamentary Paper prepared after the outbreak, in 1920, identified:

Poor nourishment, and poor living standards contributed directly to the spread of pneumonic influenza…while the rich could pay for private nurses to care for sick family members, parents and children in poor families were frequently sleeping together in shared beds, with inadequate blankets, and were often left penniless once the household breadwinner became ill.[16]

As the pandemic ravaged the community, few people ventured into public spaces, and everday life in Parramatta ground to a halt. The impact on commercial and business activities across the area was profound. In turn, with the breadwinner of many families lost to the disease, seriously ill, or unemployed, the Relief Depots established across the Parramatta area struggled to support the large and increasing number of residents suffering financial hardship.[17]

Pandemic in Parramatta: The Influenza Outbreak of 1919 (Part 3) explores losses during, and eventual recovery from, the pandemic in Parramatta…

Michelle Goodman, Council Archivist, 2019

References:

[1] Minutes of the Meeting of the Parramatta Municipal Council, 13 January 1919

[2] Parramatta Municipal Council Correspondence Register, PRS01/004, No.50

[3] Minutes of the Meeting of the Granville Municipal Council, 4 February 1919

[4] Parramatta Municipal Council Correspondence Register, PRS01/004, No.95

[5] Minutes of the Meeting of the Parramatta Municipal Council, 10 February 1919

[6] Parramatta Municipal Council Correspondence Files, PRS30/13

[7] Minutes of the Meeting of the Parramatta Municipal Council, 7 April 1919

[8] Minutes of the Meeting of the Parramatta Municipal Council, 7 April 1919

[9] Minutes of the Meeting of Dundas Municipal Council, 16 April 1919

[10] Artenstein, A.W. (Ed.). (2009). “Influenza”, Vaccines: A Biography, pp. 191-205

[11] Minutes of the Meeting of Dundas Municipal Council, 19 February 1919

[12] Inoculation Depot (1919, 22 February). Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrower’s Advocate, p.8

[13] At Ryde (1919, 5 April). Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrower’s Advocate, p.12

[14] Armstrong, S. (1980). The pneumonic influenza epidemic of 1919 in New South Wales. Student Research Papers in Australian History, No.5. the Department of History, University of Newscastle, p.14

[15] Influenza pandemic: 1919, Influenza reaches Australia, from https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/influenza-pandemic, retrieved 2 April 2019

[16] Parliamentary Papers (1920, Volume 1). Outbreak of Pneumonic Influenza in New South Wales in 1919. Section V, Part 1, pp.171-172

[17] Minutes of the Meeting of Dundas Municipal Council, 2 April 1919