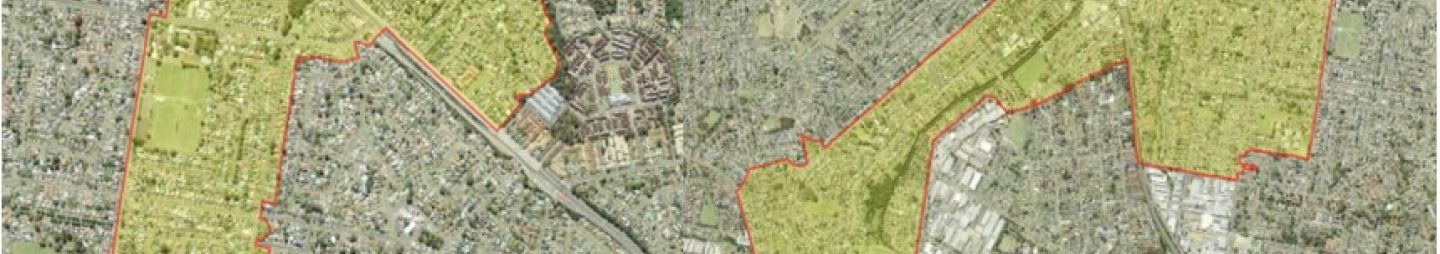

Aerial photograph of Old Toongabbie and Toongabbie (Source: Six Maps)

Traditional Custodians

The traditional custodians of the land that was to be named Toongabbie are the Tugagal clan of the Dharug people. The clans of this area lived along the waterways and were sustained with the abundance of plant and animals life from the streams and bushland.

New Ground

In 1788 the Parramatta area was settled, then called Rose Hill, as a government farm for the colony. However, by 1791 there was a need to locate another government farming area to avert a food shortage. This new land as called ‘new ground’ by David Collins in 1791 was approximately 2.4 kilometres from Parramatta. This new area would be known as Toongabbie, an Aboriginal word, possibly meaning ‘a place near the water’. The new government farm was tranquil and situated at the meeting of Toongabbie and Quarry Creeks.

This land came under the supervision of Thomas Davency, who was given five hundred convicts to work the land. As reported by Watkin Tench in December 1791. ‘six weeks ago this was a forest; it has been cleard and wood nearly burnt off the ground by five hundred men…in thirty day….’. Convicts who worked on the cultivation ground and later farm included many from the third fleet and as noted by George Thompson, of the Royal Admiral in 1792 the working conditions of the convicts at Toongabbie were very bleak and their lives extremely hard.

“They are allowed no breakfast hour, because they have seldom anything to eat. Their labour is felling trees, digging up the stumps, rooting up the shrubs and grass, turning up the ground with spades or hoes, and carrying the timber to convenient places. From the heat of the sun, the short allowance of provision, and the ill-treatment they receive from a set of merciless wretches (most of them of their own description) who are their superintendents, their lives are rendered truly miserable. At night they are placed in a hut, perhaps fourteen, sixteen, or eighteen together (with one woman, whose duty is to keep it clean and provide victuals for the men while at work), without the comfort of either beds or blankets, unless they take them from the ship they come out in, or are rich enough to purchase them when they come on shore. They have neither bowl, plate, spoon, or knife but what they make of the green wood of this country, only one small iron pot being allowed to dress their poor allowance of meat, rice, &c.; in short, all the necessary conveniences of life they are strangers to, and suffer everything they could dread in their sentence of transportation. Some time since it was not uncommon for seven or eight to die in one day, and very often while at work, they being kept in the field till the last moment, and frequently while being carried to the hospital. Many a one has died standing at the door of the storehouse waiting for his allowance of provision, merely for want of sustenance and necessary food.”

During 1792, there was 1000 acres of land in use at Parramatta and Toongabbie that were farming maize, wheat and barley. Despite the difficulties faces by the convicts working this land, Before he left for England Governor Phillip took pride in this result; “Toon-gab-be…the soil is good…and I flatter myself that the time approaches in which this county will be able to supply its inhabitants with grain…”

Land Grants

Under the acting Governorship of Francis Grouse and William Paterson, from 1793-95 the land became known for private property as well as government farm land. This occurred through the issue of a large number of land grants around the cultivation area set out by Philip.

Thomas Daveney, the superintendent of convicts at Toongabbie was one of these recipients; he received 100 acres in 1794. Others who were given land included, Daniel Kelly, Edward Jones and William Joyce, all ex-convicts. There were seventeen grants allocated in between 1793-1795, and they were a mix of military families and ex-convicts. The grants were immediately around the farming land and this lead to an inability to further expand the farming area.

An Increase in Live Stock.

From 1795-1800 under the Governorship of John Hunter the total government stock was at 30 horses, 765 cattle. 625 sheep, 12 goats and 9 pigs, with many of these kept at Toongabblie Farm.

And from 1800-1806 there was other changes that effected the role of the Toongabbie Farm in substantial ways. There was now plans in place to set up a new government farm at Castle Hill. In addition, in 1803 this farm was working alongside the Toongabbie Farm. In 1802, Surgeon and magistrate James Thomson gave a description of the Farm.

“…is Toongabbie, a small settlement where the Government keeps its chief stock of cattle and a number of convicts who cultivate between two and three hundred acres…The land here is good, and tho’ often cropped and little manure produces 18 bushels per acre”

From 1804, many women who had worked at the Toongabbie Farm were moved to what was to become the first Female Factory. But some did remain at the fam and they were employed as dairy maids. One, a Nelly McDonald was in charge of the milk house until 1803.

Toongabbie during Macquarie’s time:

The conditions seen by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810 at the Toongabbie Farms were problematic. “the houses or huts of the settlers are very bad, mean and inconveniently constructed; themselves and their families badly clothed and apparently very ill and poorly fed.” Macquarie stated that he would see to it that the government assistance.

But there were two settlers in the Toongabbie area that were prospering, George Best and John Pye. “Very industrious respectable settlers who have their farms well cultivated and in most excellent order, with good offices, and comfortable decent dwelling houses.”

George Best and his wife and family had become pioneering pastoralists in the Toongabbie area. After acquiring land north to the barley and wheat fields of the farm, Best took to live-stock and in 1818 was able to supple 4000 unites of fresh meat to the Government Supply.

John Pye’s land holdings started small, with Pye Farm. However by 1806 John and Mary had twenty-five acres of wheat, forty-one acres of pasture, twenty acres of maize, five of fallow, four of barley and one of orchard. Plus, oxen, and sheep. When he passed away in 1830 he left seven properties, in Toongabbie to his children. One of these children James Pye would become an internationally known orchardist and a man of many accomplishments.

The Beginning of a Town.

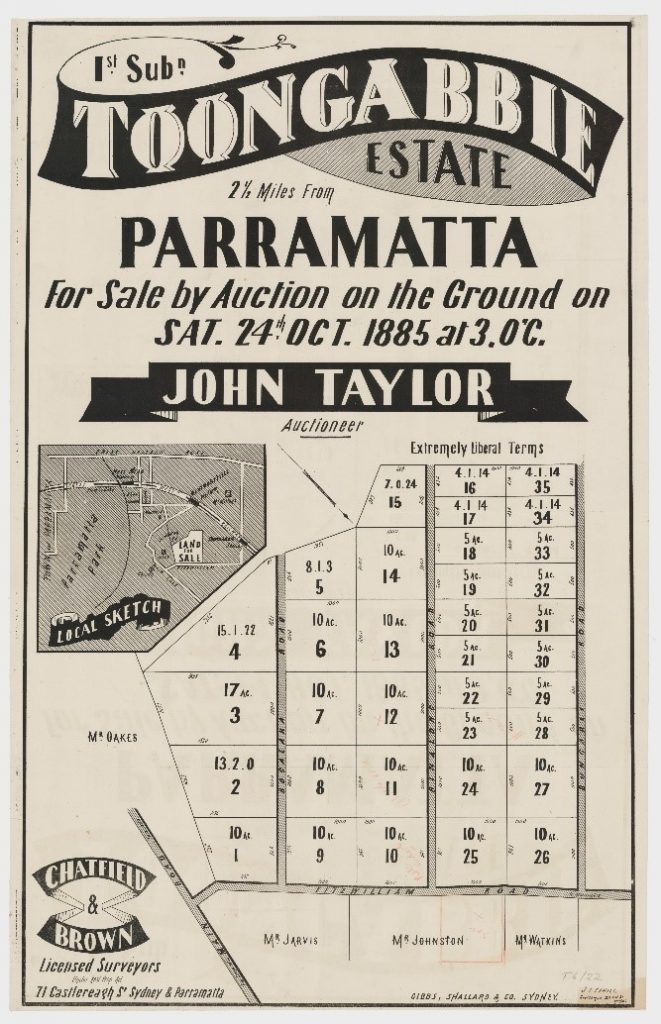

From 1810 to 1850 the Wentworth Family and George Oaks acquired much of the land that was originally the Government Farm area

700 hectares at Toongabbie, including the old village site, remained officially unoccupied either by government or lessees in 1825, this was a result of Lachlan Macquarie’s ungranted land bid. And It remained part of the Parramatta Domain until subdivision in 1860-61. Now 240 hectares, comprising the entire site of the former Government Farm and much of its adjacent farm lands, were purchased by a single proprietor, George Oakes, in 1861 and was used for grazing.

From 1860 to 1880 Toongabbie grew with small family farms. They occupied small farms that varied in size, from a few acres to up to thirty-four acres.

Development: Railways, Education, the Post.

During the late 1800’s Toongabbie saw advancements that would change a way of life.

Toongabbie acquired its own railway station on the 26 April 1880. At first it was unmanned and was in the form of a small shed. The station was mainly for goods at this time and any passengers had to signal the trains driver if they wanted to board the train. The station acquired its first station master in 1890, Miss Am Arnold. The line was updated in 1886 and then in the 1940’s.

Education was compulsory for all children up to the age of fourteen from 1880. To this, a classroom was set up in the Primitive Methodist Church for twenty-seven children in May 1886. In 1889 there was a need for a school house to be built and this was opened in 1890 and used by forty children. The school acquired its first brick building in 1923.

Today Toongabbie and Old Toongabbie has several schools including Toongabbie Public School, Toongabbie West Public School, Toongabbie Christian School and Metella Road Public School.

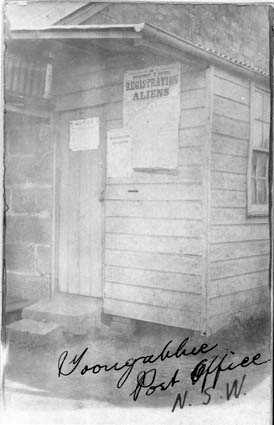

The first post office in Toongabbie was opened in a private home, that of Henry Birk in August 1887. A second post office was opened in 1922, and it was only in 1960 that the post office was officially named, Toongabbie Post Office.

Modern Times:

At least thirty-nine soldiers embarked from the Toongabbie area and sadly some of them were killed in action. For a small community this loss was felt keenly.

Between the World War One and Two a slice of life is spoken of in Toongabbie: A Social History:

“In the 1920’s Toongabbie was still a small rural area with a few dairies, poultry farms and small orchards….Most homes had a few fowls and many grew their own vegetables..some were lucky enough to have a cow…children spent most of their time outdoors…many social activities were held at the School of Arts…concerts, fancy dress balls….during the Depression many men were out of work…some were forced to sell door to door to keep food on the table….steam trains ran regularly…and the shopping centre…had only a couple of small shops and the Post Office…bread and milk was delivered….”

It was only in the 1920’s that the Toongabbie area was supplied with electricity.

Today:

The name Old Toongabbie is given for the suburb that is alongside the creeks. And came into use to distinguish the older part of the suburb from the suburb that grew around the 1880 railway station. It includes the original farm and settlement.

In 2016, 14,337 people lived in Toongabbie. The suburb has a young population with a median age of 35 years; and children aged 0 – 14 years made up 20.1% of the population.

54.8% of Toongabbie’s population were born in Australia; with the next most common countries of birth being India, Sri Lanka, China, Philippines and New Zealand.

Old Toongabbie has a much smaller population. In 2016 it was 3,133. The population is older when comparted to Toongabbie with 487% of the population aged 30-65 years.

Emma Stockburn, Research Facilitator, Family History, City of Parramatta, Parramatta Heritage Center, 2020

References:

Darug Tribal Aboriginal Corportion: https://www.darug.sydney/history

The Journal of George Thompson: Historical Records of New South Wales: p793 -796

Phillip in Dundas Historical Records of New South Wales p625.

Thompson to Cooke, Historical Records of New South Wales, 5 p. 390.

Toongabbie’s Government Farm: An elusive vision for five governors 1791 – 1824, Barkley-Jack, Jan, Snap Printing, 2013.

Toongabbie – A Social History – 1860-1940, Toongabbie and District Historical Society. 2011.

The Book of Sydney Suburbs, Pollon, Frances, Angus and Robertson, 1988.

Add Collin and Tench.

Journal, Lachlan Macquarie https://www.mq.edu.au/macquarie-archive/lema/ (Retrieved 30/10/2019.)

DEPUTY COMMISSARY GENERAL’S OFFICE, Sydney, 27th, June, 1818. (1818, July 25). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), p. 4. Retrieved October 30, 2019

Home of George Best: Fairholme: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=1140123 (retrieved 30/10/2019.)

Toongabbie Farm Archaeological Site: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5061406 (retrieved 30/10/2019),

Toongabbie Railway Station. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toongabbie_railway_station (Retrieved 1/11/2019)

The Toongabbie Story, Doris A Sargeant, Parents and Teachers Association, Toongabbie Public School, 1964.

Old Toongabbie and Toongabbie; Dictionary of Sydney. https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/old_toongabbie_and_toongabbie. (retrieved 1/11/2019).