Medical and nursing staff in Parramatta, c. 1890. (Source: City of Parramatta Reference Library Photographic Collection)

The concept of ‘nursing’ is fluid. Many Indigenous societies, including the traditional custodians of the Parramatta area, the people of the Darug Nation, do not separate out the role of the ‘nurse’ in their holistic approach to health. In Western societies, the term ‘nurse’ has been used historically to describe a range of caring occupations, including uncertified midwives and those employed to care for healthy young children.

The term ‘nurse’ also has a gendered history, with a feminisation of the role occurring during the nineteenth century, perhaps most potently illustrated by the declaration of pioneering British nurse Florence Nightingale that ‘every woman is a nurse’.[1] Of course, reintroduction of men to the nursing profession was well underway by the mid-twentieth century.

The specific focus of this article, drawing from the late local historian John McClymont’s Medical History in Parramatta, is the historical context of nursing care provided in medical hospitals in Parramatta.[2],

The ‘Tent’ Hospital, 1789 – 1792

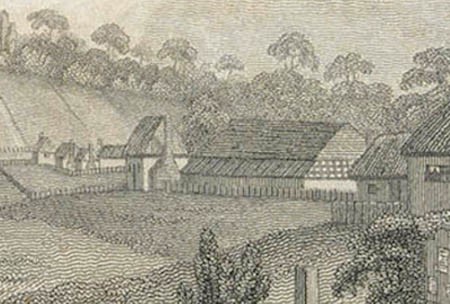

The ‘Tent’ Hospital at Parramatta, c. early-1790s. (Source: State Library of New South Wales)

In November 1788, the primary settlement of Parramatta, known as ‘Rose Hill’ until 1792, was established upstream from Sydney Cove, under the Colonial rule of Governor Arthur Phillip. The settlement saw about 800 convicts land, many of whom were in poor health from their imprisonment in Britain prior to transportation, and their long journey to the Colony.

Within a year of settlement, a temporary ‘tent’ hospital, comprising of two long sheds with an overarching thatched roof had been constructed. The hospital was built primarily to treat outbreaks of dysentery among convicts (members of the military who fell ill were treated in their barracks).

The ‘tent’ hospital was a roughly-built structure, 80 feet long and 20 feet wide, capable of accommodating two hundred patients. The hospital’s ‘tent’ structure was probably gradually replaced with timber walls and a thatched roof.

Conditions in the ‘tent’ hospital were desperate, and hygiene standards were almost non-existent. Indeed, Captain Watkin Tench recorded in mid-November, 1790:

“A most wretched hospital, totally destitute of every conveniency. Lucky for the gentleman who superintends this hospital, and still more lucky for those who are doomed in case of sickness to enter it, the air at Rose Hill has been generally healthy.”[3]

It was on this site that the story of hospital nursing began in the new colony with the doctor in charge, Surgeon Arndell, being assigned convicts to nurse the sick. At this early stage, male attendants supervised male patients, and female attendants supervised female patients.

The Second Parramatta Hospital, 1792-1818

The town of Parramatta, c. 1792. (Source: Parramatta Heritage Centre website)

By 1792, it was apparent that the conditions in the ‘tent’ hospital were so dire that a new hospital structure was required and in the April of that year Governor Phillip laid the foundations for a new hospital.[4] Comprising two wards, one each for male and female patients, the hospital was 80 feet long and 20 feet wide, built of locally made bricks. In December 1792 patients from the ‘tent’ hospital were transferred into the new building.[5]

Located to the north of the first hospital, the new infirmary was about 100 meters from the Parramatta River bank, “convenient to the water”. To prevent “any improper communication with other convicts” it was enclosed with a paling fence, with space around the hospital “so that the sick would have every advantage of both air and exercise”.[6]

Convicts selected to assist in the hospital were usually those too old or infirm to undertake arduous duties in the normal workforce. Deployment of convicts in 1806 show that the roles of nurses were undertaken by seven convict women. No reward was given to them for this work other than their usual living allowances of food.

Parramatta Colonial Hospital, 1818 – 1848

The Parramatta Colonial Hospital, by Joseph Lycett, 1824. (Source: State Library of Victoria)

The Parramatta Colonial Hospital, by Joseph Lycett, 1824. (Source: State Library of Victoria)

Less than twenty years after its construction, the second Parramatta Hospital was in a very poor state of repair and Governor Macquarie came under pressure to provide more appropriate medical services. Macquarie commissioned a new Colonial Hospital, which was completed by September 1818.[7] The hospital was located facing Parramatta River, to the east of the second hospital.

Governor Macquarie’s own written description of the hospital reads:

“A hospital built of brick, two stories high with an upper and lower verandah all round with all the necessary out offices for the residents and occupation of 100 patients with ground for a garden and for the patients to take air and exercise in, the whole of the premises being enclosed with a high strong stockade.”[8]

The Colonial Hospital consisted of four wards, three of which were for female patients, and one for males. It contained fifty beds, although it was recorded the average number of patients during the years 1841 and 1842 was between sixty and seventy, making necessary to make up beds on the floor.

Convicts continued to be selected to provide nursing care at the hospital. ‘Midwifery cases’ were at this time cared for at the hospital within the Female Factory in North Parramatta.[9]

The Macquarie Hospital, 1848 – 1897

Hospital medical and nursing staff in Parramatta, c. 1890. (Source: City of Parramatta Reference Library Photographic Collection)

When the transportation of convicts to the Colony ceased in 1848, the hospital transferred from Colonial administration to management by a local committee. The first committee meeting appointed two well-known local doctors to superintend the hospital. An advertisement lead to the successful placement of a hospital matron, who undertook administrative, rather than pateint care duties. During 1848 a cook, a wardsman, and a nurse and washerwoman were appointed.[10]

In the 1860s, the Macquarie Hospital was described as having comfortable, cool rooms, with high ceilings. A library of books for was available for patients to browse, and games of draughts were played with the patients by the master of the hospital.[11]

At this time, the vocation of nursing was poorly paid and low status. Nurses, regarded as little more than general housemaids, underwent no formal training. With the advances in medicine however, the need arose for skilled assistants who could interpret the necessity for cleanliness and orderliness and undertake the routine daily medical instructions required by medical staff.

The first training school for nurses in Australia commenced at Sydney Hospital in 1868, eight years after Florence Nightingale began her renowned training of nurses at St Thomas’s Hospital, London. The first Nightingale-trained nurse to be appointed Matron at Parramatta was a Mrs Pearson, who commenced duty on 1 March 1876. In 1877, Matron was given the authority to suspend any employee under her charge and manage the administration of the hospital.[12]

With the health needs of Parramatta continuing to increase, in 1882 a new two-storey wing was added to the Macquarie Hospital, and in 1884 a separate pharmaceutical dispensary was established under the care of the matron.

In 1888, when extra funds became available for the hospital following a bequest, it was decided to appoint a secretary to care for the daily administration and thus allow the matron to focus on supervising management of the nurses and other hospital staff.

By 1891, the hospital had two wards for male patients, one ward for female patients, a private ward and nurses’ quarters. However, the financial downturn during the 1890s saw stringent economies throughout the hospital due to the financial depression of the times. In 1892 Matron Greenwood is recorded as having reduced the dispensary drug bill considerably, and she was highly praised in that year’s hospital Annual Report.[13]

In 1896, Nurse Rutter was appointed Matron and brought the profession into great respect through her managerial and medical skills. When in 1906, she was praised for the thoroughness of her work, the Board of Directors recorded that the doctors regarded her as equal in ability to a resident surgeon. Matron Rutter retired in 1912, after 16 years in the position.[14]

Parramatta District Hospital, 1897-1943

Parramatta District Hospital, c.1940s. (Source: City of Parramatta Council Local Studies Photograph Collection, LSOP00157)

Medical care needs in the Parramatta area continued to grow and on 24 January 1896 Viscount Hampden, Governor of NSW, laid the foundation stone of the first section of the new Parramatta District Hospital building. This section was completed by the December of that year at a cost approximately £1,200, and comprised of two large medical wards and an infectious isolation ward. Patients were transferred from the old Macquarie Hospital to the new building in January 1897.

The second section of Parramatta District Hospital was completed in 1898-9 and it is assumed that at this time the old hospital was demolished. In August 1901 the final remains of the 1818 hospital, the old stables, doctors’ residence and smoking shed were removed, bringing to an end the long era of the Macquarie Hospital.[15]

The Parramatta District Hospital building was located to the west of the old hospital, also facing Parramatta River, in a composition of three blocks built in the Federation Queen Anne Style. The central block was two storeys, with a hipped roof of Marseilles pattern terracotta tiles, and on the ridge-line were two massive chimneys, each with six terracotta chimney pots. The block was three-bayed, with louvres to the upper windows and on each side there were spacious verandahs. A contemporary description reads:

“A hospital up-to-date in every respect… large and commodious wards… male and female surgical, male and female (medical) – an infectious ward – private wards – an excellent operating theatre – also a splendid administrative block, well-furnished throughout.”[16]

From as early as 1910, there were plans for the construction of additional living quarters for the nurses at Parramatta District Hospital. Nearby Brislington House had been rented from the Brown family for nurses’ accommodation, but over time this provision became increasingly insufficient. Plans were made in 1923 with the Public Works architect to build two storeyed accommodation for 28 nurses, located to the west of the hospital. Designed with verandahs twelve feet wide, it included a dining room, sitting room, kitchen, toilets and bathrooms, in 1925 the nurses’ accommodation was finally opened.[17]

Over coming years, Parramatta District Hospital required enlarging and the succeeding years saw numerous alterations and additions. In 1926 a casualty room, a staff dining room and accommodation for the matron and the resident medical officers were added. The 1930s saw the depression years resulting in the curtailing of costs with building, wages and salary cuts.

Jeffery House, 1943-1990s

Jeffery House, c. 1970s. (Source: City of Parramatta Council Community Archives)

A multi-storey building, in the ‘modern’ style, to accommodate increasing health services needs, was opened on the Parramatta District Hospital site in 1943.[18].

By 1945 the Parramatta District Hospital Board began discussing with the Hospitals Commission the necessity for improved maternity services.[19] Consideration was given initially to the conversion of the top floor of the new building into a dedicated maternity ward. However, it was finally agreed that a separate prefabricated maternity hospital wing would be constructed, which was eventually opened by opened in November 1955.

In September 1956, Mr PH Jeffery, who had been chairman of the Parramatta District Hospital Board for 26 years, did not seek re-election. In April 1957, the Board resolved to call the main building Jeffery House in honour hof his loyal and untiring service.[20]

Complementing the modernised buildings of the hospital, this period also saw significant changes to the conditions for nurses at the Parramatta District Hospital. The employment of married nurses, which had been introduced during the Second World War due to staff shortages, was continued. In addition, male nurses began to be employed, with Board minutes of 1945 recording the successful application for employment as a nurse of a Mr Shaw. In 1946, nurse’s hours were reduced to 40 per week, and, by 1967, it was decided that nurses were no longer required to ‘live-in’.[21]

The Parramatta Hospitals, 1978 – 1990s

The Westmead Centre under construction, c. 1977. (Source: City of Parramatta Council Community Archives)

The increasingly complex health care needs of the growing Western Suburbs of Sydney led to the announcement in the early-1970s that a state-of-the-art teaching hospital would be constructed in the Parramatta local government area suburb of Westmead. The Westmead Centre accepted its first patient on 1 November 1978, and was officially opened on 10 November, by the Premier of New South Wales.

In February 1978, it was announced that Parramatta District Hospital would be fully integrated with the Westmead Centre, and the Board of Directors would comprise three from the Parramatta Board, three from Sydney University and six from the general public. By the end of 1978, all acute health services had been relocated to the Westmead Centre, and the old Parramatta District Hospital building began accommodating rehabilitation services.

Westmead Hospital, 1990s onwards

Westmead Hospital, c. late-1990s. (Source: City of Parramatta Council Archives)

In 1991, all health services were moved out of the old Parramatta District Hospital building. In 1995 the building was decommissioned and redeveloped into the Parramatta Justice Precinct. The Parramatta Community Health Centre, located in Jeffery House, still operates on part of the original site.[22]

In 2016, a major $1.1billion upgrade of Westmead Hospital was announced. The Westmead Redevelopment Project, now nearing completion, will transform the precinct into an innovative, contemporary and integrated centre which will continue to deliver high quality healthcare for decades to come.[23]

Nurses and midwives at Westmead Hospital continue to provide world-class professional health care services for the people of Parramatta, and the wider Western Sydney community.

The Nurses of Parramatta

Nurses on duty in Westmead Hospital’s Emergency Department, c. 2019. (Source: wsldh.nsw.gov.au)

The nursing profession traces a fascinating history through the medical hospitals of Parramatta. From the unnamed men and women who worked in the dismal conditions of the first ‘tent’ hospital, and the untrained midwives delivering babies at the Female Factory, through to the professional nurses and midwives of today, providing specialist care in increasingly complex medical settings.

The International Year of the Nurse and Midwife celebrated in 2020, a year that saw the most significant public health event for more than one hundred years in the COVID-19 virus pandemic, is an appropriate time to reflect on the fascinating history and significant contributions of nurses in hospitals within the Parramatta local government area, and beyond.

Michelle Goodman, Council Archivist, 2020

(Featuring research by the late local historian John McClymont)

References:

[1] Nightingale, F (1860), Notes on Nursing: What it is and what it is not, New York.

[2] McClymont, J (1999), Medical History in Parramatta, self-published.

[3] Tench, W (ed L. Fitzharding) (1793). Sydney’s First Four Years, London, p. 196.

[4] Collins, D (ed B. Fletcher), (1804). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London, p. 173

[5] Collins, D (ed. B. Fletcher), (1804). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London, p. 207

[6] Collins, D (ed. B. Fletcher), (1804). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London, p. 207

[7] Jervis, J, (1961). The Cradle City of Australia: A History of Parramatta, 1788 – 1961, Parramatta , p. 120.

[8] ‘Macquarie to Goulburn’, HRA, i, 10, 1819-1822, p. 689.

[9] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.26

[10] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.31

[11] Kass et al, (1996). Parramatta: A Past Revealed, Parramatta, p. 208

[12] Chisholm. A (1958), ‘Nursing Profession’, Australian Encyclopaedia, vol 6, Sydney

[13] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.45

[14] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.50

[15] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.49

[16] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.49

[17] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.49

[18] https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=3540616, retrieved on 29 April /2020

[19] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.64

[20] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.64

[21] Horton, B (ed), (1988). Caring for Convicts and the Community, Sydney, Cumberland Area Health Service, p.72

[22] “Parramatta Community Health Centre – WSLHD”. wslhd.health.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 28 April 2020

[23] http://www.westmeadproject.health.nsw.gov.au/precinct/our-vision-for-westmead, retrieved on 28 April 2020