Throughout the 1870s a number of women patients were housed in the inappropriate prison cells constructed by Governor Gipps in 1838-1839.[1] Dr. Manning, the ‘Inspector of the Insane’, conducted two reports (1868 and 1877) which challenged the current system and appears to have been one of the main factors in upgrades being made to the buildings and structures over the 1880s.[2] The following conditions in the old prison yard were described in 1877,

The lunatic women, whether free, convict or criminal, occupied one large yard surrounded by high prison walls. The yard was partly grassed, but had no gardens and was divided by a paling fence which separated the aged and sick from the others. The aged and sick occupied three rooms and the others slept in ‘the old factory’, described as a ‘gloomy, three-storied building’ with cells, the internal corridors of which are so dark that it is never brighter than twilight on the sunniest day. This is thought to be the 1838-39 punishment cell wing. The entrance door was only 18 inches wide and there was no glass in the windows.”[3]

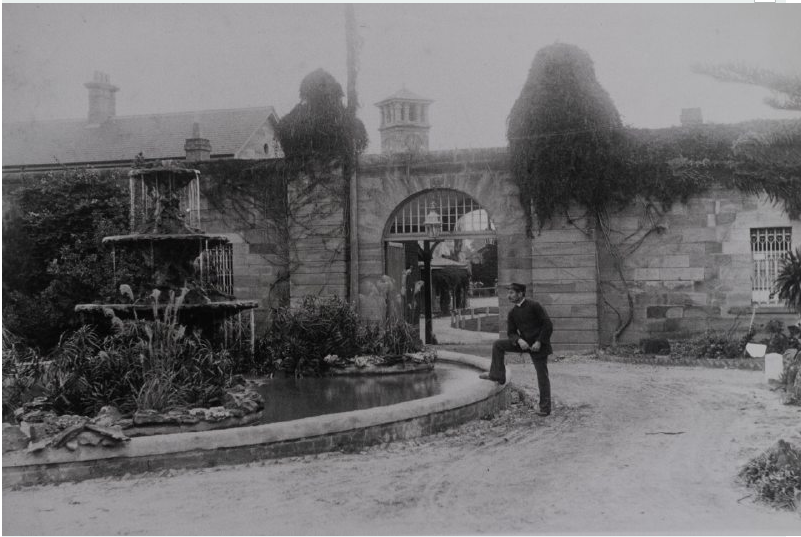

By August 1882 a large single story weatherboard complex for women had been completed and the patients moved in.[4] The building was in the northern part of the Vineyard estate acquired from John and Ellen Blaxland, and once the property of Reverend Samuel Marsden but the moment of the patients was to have a momentous effect on the old ‘female factory’ precinct. As a result of the movement of the female patients into their new accommodation approval was given in August 1882, to destroy the 1838-1839 prison cell complex they had vacated.[5] By 31 may 1884 the walls of the new Asylum building were up and workmen were completing work on the roof. Rather than waste the sandstone blocks from the old Gipp’s ’female factory’ cells the administration used them to construction of this building. Known as the ‘Institute of Psychiatry Building’ it was completed by June 1885 and it is still standing on the site today (along with the original clock from Greenway’s ‘female factory’ building).[6] A Dining Block behind the Psychiatry Building was completed at the same time and this is also still standing on the Cumberland site. Ward 4, the ‘wet and dirty’ building for those suffering from incontinence was built in 1889. This building had special drainage and ventilation and was attached to the original ‘female factory’ dormitory building erected for 3 class female convicts around 1825 (both still stand today although in a modified state). [7] While construction of buildings was a focus of changes to the asylum it was around this time that the grounds and gardens also started a new phase of re-design. Central to this was the appointment of William Cotter Williamson as Assistant Medical Superintendent in 1883. Cotters interests in the Sydney Gardening Movement, ensured the gardens, and the beneficial effects of these areas for the patients were more fully acknowledged.[8] One of the first areas to be redeveloped was the site of the former ‘female factory’ which was laid out as gardens and shrubbery after the demolition.[9] Even these new buildings were not enough to alleviate the pressure and on the 10 July the Official visitors to the Parramatta site addressed a letter to the Colonial Secretary about conditions at the Parramatta Asylum.[10] In an attempt to deal with the increasing demand for psychiatric services ‘Callan Park’ in Roselle was opened in 1884. But even this could not alleviate the demand and in 1888 the Protestant Orphan School at Rydalmere was acquired and converted to an Insane Asylum. Over 1889 and 1890 an impressive new sandstone building was erected on the ground at Parramatta. This building referred to in some reports as Male Ward 4 (or building 106) was on the western side of the original precinct and faced onto the river. Housed here were the dangerous and refractory non-criminal males.[11] By 1892 the buildings were already over-crowded and in 1903 the additions made to No. 4 Ward were completed at a cost of 2703 pounds along with extensions to the laundry.[12] The removal of the old entrance gates around 1909 saw the central complex of the Asylum opened up and the new visiting and office block which replaced them was completed in 1910. The staff dining room and kitchen were completed in the same year[13] By 1934 there were 700 women patients crammed into the buildings. The Criminal Lunatic Ward No 5 was demolished in 1963 and was replaced with a staff car park and walls were demolished as a part of a new open ward policy. Construction of a new medical centre to become the central medical unit began in 1966 and was completed in 1967.[14] This was followed by the intensive care facilities and renovation of the ‘chronic male block’ inot wards; 9, 10 and 11.[15] In 1970 replacement of the weatherboard ‘female division’ allowed the patients to be moved out and the old buildings were then demolished.[16] The name of the complex was changed to Cumberland Hospital in 1983.

Geoff Barker, Research and Collection Services Coordinator, Parramatta City Council, Heritage Visitor Information Centre, 2015

References [1] Weatherburn 1990, citing Report of the Inspector of the Insane, 1877, cited in Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 65 [2] Weatherburn 1990, citing Report of the Inspector of the Insane, 1877, cited in Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 65 [3] Weatherburn 1990, citing Report of the Inspector of the Insane, 1877, cited Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 61 [4] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1883, p.16, cited in Higginbotham, p. 40 [5] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1883, p.16, cited in Higginbotham, p. 40 [6] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1885, p.16, cited in Higginbotham, p. 40 [7] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1891, p.19, cited in Higginbotham, p. 40 [8] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1883, p.16, cited in Higginbotham, p.40 [9] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1885, p.16, cited in Higginbotham, p.40 [10] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1887, p.16, cited in Higginbotham, p.41 [11] T Smith, Hidden heritage, greater Parramatta Mental health Services, 1999, p.20 [12] Public Works, Annual Reports, 1903, p.43 [13] Public Works department Plans, MH9/37, MH/60, Visiting and Office Block, 31.5.1909 [14] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1966, p.45, cited in Higginbotham, p.60 [15] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1968, p.26, cited in Higginbotham, p.60 [16] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 65