Over the years, the City of Parramatta Council has taken many photos to record its events, activities, buildings and achievements. One of the roles of the Parramatta Heritage Centre is to preserve these images in its archives.

Beyond simply preserving and assisting with access to the records of the past, the centre’s role is to help the community interpret this information in an impartial manner (Cassell & Hiremath, 2013, p. 4).

In modern society photographs are everywhere. Everyone has a camera in their phone, documenting their lives through photos. But 50 years from now will anyone know what these photos are of? What story are they telling? Who’s in them? When and where were they taken? What was the occasion? Some of this information is captured automatically; the time and location are recorded for us, and comments and tags on social media can help, but these basic details don’t tell the whole story. In 50 years, will anyone remember that the date the photo was taken was the anniversary the day the people in it first met? That the GPS coordinates are the location of a favourite spot in the local park? Without understanding the context of the photo, much of the story and its meaning are lost.

Before digital photography even these basic details weren’t recorded. The only information about what’s in a photo is what was written on the back of the print or the photo envelope. An image without context doesn’t tell a story, it’s just of photo of unknown people, places and things. And it’s not just what’s in the photo that’s important; knowing who took a photo and why they took it is essential to understanding the content and its importance. [1] A photo may be of great interest to the historians of tomorrow, but if we can’t describe what’s in photo, how will they be able to find it?

This gives you an idea of the problems faced by archivists in their efforts to preserve and catalogue the historical record for future generations. Over the centuries, techniques have been developed to retain as much meaningful information as possible. It’s not just a matter of preserving photos (or documents, or artefacts), it’s about preserving their context so that we can understand the story they are telling. [2]

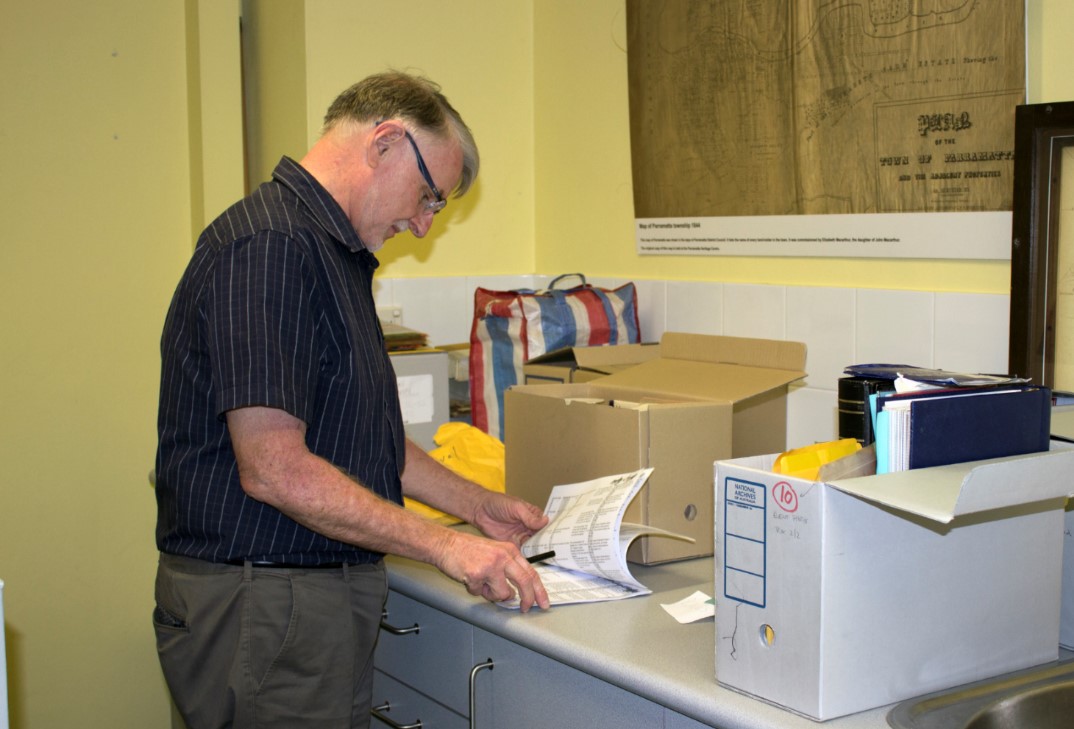

In this blog post I’ll illustrate the difficulties that arise when cataloguing images taken by the council. In doing this I’ll explain some of the principals and techniques used by archivist to retain as much as possible of the context of the items stored. As an example, I’ll describing a project I was recently involved in to catalogue a collection of pre-digital council photos.

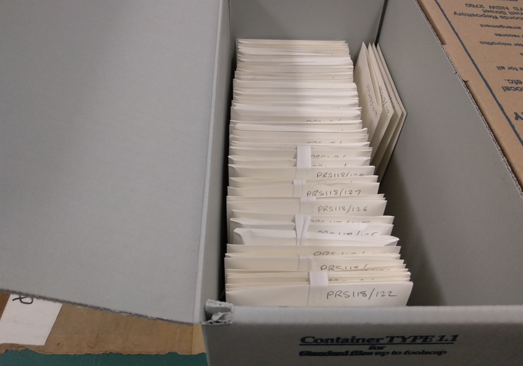

The photo collection consisted of ten boxes containing bundles of photos, albums, loose prints, and negatives. Some had annotations but many did not. Dates ranged between the early 1980s and 2003. All originated from sources within the council, but the details of who took them and why had been lost. Any original organisation of the photos into groups had also been lost; they were all jumbled together. Many photos were in the paper envelopes in which they returned from a photo developer. These envelopes were different colours depending on the company that developed the prints. Some envelopes had no dates written on them but had reference numbers such as “S137”, the meaning of which had been lost.

The goals of this project were to:

- organise the collection into a meaningful order,

- write catalogue descriptions of the images so they can be found by researchers searching for photos of specific topics,

- repackage the collection for long term storage (the first step was to decide how best to organise the photos).

Keeping the “Original Order”

One of the key principals in archiving is that of “original order”. [3] This says that when you are preserving a document (be it photo, letter, or something else) you should wherever possible store it organised in the same filing system that was used when the document was in use. So, if it’s a paper document in a filing cabinet with other documents, then you should keep all the documents in the same order that they are in the file cabinet. Where the document is in the file provides context about the document; it provides information that helps add meaning to the document (Bettington et al., 2008, p. 635).

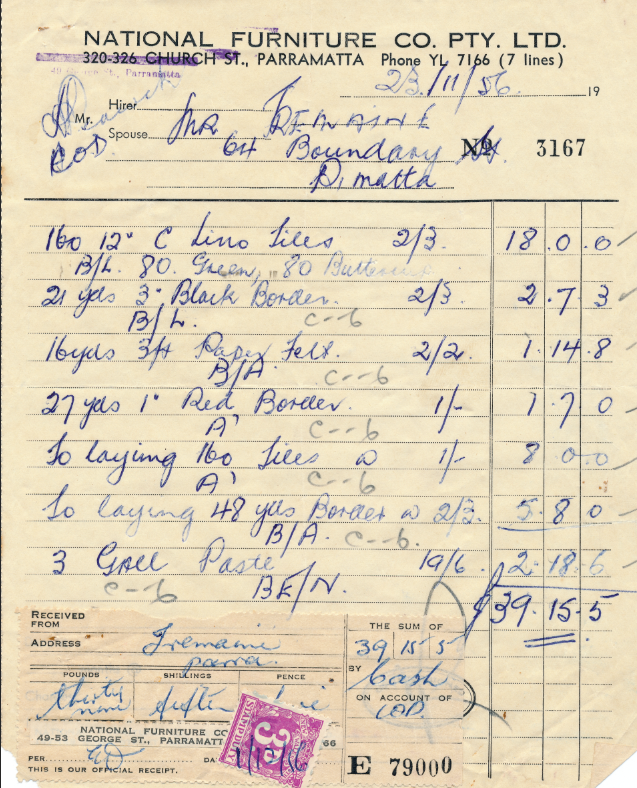

Let’s look at an example from another collection within the council’s community archive. The Tremain collection consists of papers and artefacts belonging to the Tremain family, who lived in the local area in the late-1800s. One of the items in this collection is a receipt for the purchase of household furniture and linens from a local department store. Now, the archivist could decide that this is an excellent example of a retail receipt of the period and so catalogue it with other retail artefacts of the period. Doing so however would lose information about the receipt. All we would know is what is written on it; we wouldn’t know why the items were purchased, or where they were to be used.

If we look at where the receipt was located within the other Tremain papers – if we keep the papers in the original order in which they were stored by the family – then we can determine a lot more about the receipt.

The receipt was filed with other papers that were in chronological order. The first papers in this file related to the purchase of a property and were followed by papers relating to the construction of a house on that property. Our receipt dates from a period after the property was completed, so the items were being purchased to furnish the house. By keeping the papers in their original order, we now know why the items on our receipt were purchased, by whom, and where they were to be used.

In the case of our photo collection the original order had been lost, so what should we do? In the absence of original ordering an artificial series ordering can be used (Millar, 2017, p. 63). It was decided to catalogue the images using artificial series based on the broad subject matter, so I analysed the collection to determine the broad themes covered by the collection. Based on this analysis it was decided to catalogue based on three artificial series: Events, Places, and Miscellaneous.

In preparation for cataloguing, the photo envelopes with known dates were sorted into chronological order so that the catalogue numbers could be assigned in that order. It was during this process that the importance of retaining (or in this case restoring) the original order became apparent. Many of the photos were in paper envelopes in which they returned from photo developer. These were different colours depending on the company that developed the prints. Some were blue, some yellow, and some white. When the envelopes were arranged in chronological order envelopes of the same colour were all together. It appears that the council used the same photo developer for a number of years, and then changed to another. The colour of the envelopes now conveys useful information. For envelopes with no date written on them we can now determine a rough date range based on the colour of the envelope they are in.

Further, the meaning of the cryptic reference numbers we mentioned before (eg “S137”) became clear. When the bundles with known dates were sorted into chronological order, it became apparent that bundles with similar reference numbers existed, and that the reference numbers were allocated chronologically. It therefore became possible to determine the approximate date of these undated envelopes by comparison with other dated bundles with adjacent reference numbers.

Is Everything Worth Keeping?

Another issue that needs to be considered in cataloguing the collection is the number of images. In the internet age there is an expectation that everything will be available online. [4](Stevens-Rayburn & Boulton, 1998, p. 196), so there is a natural desire to catalogue and digitise everything in a collection. In practice this is not always possible. In this case the photo collection consisted of nearly 7000 images, some of limited historical value. It would be a poor use of limited resources to catalogue every item. For example, there are many images of the historic Lennox Bridge in Parramatta. Many are undated and show no distinguishing features not shown in many other photos of the bridge. Are they all worth preserving just in case future user find a point of interest in them? Similar issues existed in the Tremain personal papers. There was, for example, a box of receipts related to the purchase of a player piano rolls. While these could each have been individually catalogued it was decided to catalogue them as a single item.

Decisions need to be made on what items are worth making available online, what should be kept in the collection but not online, and what should not be kept all (either destroyed or otherwise disposed of). These decisions need be informed by the needs of the users who will be accessing the collection, so that the best result is achieved with the most effective use of resources.

This is not a simple decision. The reasons people view the items in the archive change over time, and so the judgement of what is worthy of preservation and what is not will change over time. Archivists must make these decisions based not only on their knowledge of the collection’s current users but take into consideration possible future users. The archivist also needs to strive to avoid any cultural biases in the decisions they make, so that items of potential interest to future generations are not discard as they currently deemed of no value. [5]

Conclusion

Storing photos (or any document) for a long term preservation is more than just putting them in a box somewhere safe. Photos derive much of their meaning from the context in which they were created; who took them and why, who and what are depicted in the photo. Without understanding these, the storying being told the photo is lost.

The first step to understanding the context of a photo is to record as much as possible about the photo as close as possible to the time of creation while the details are still fresh. Modern phone cameras and social media tagging help to some degree, but there’s no substitute for a good description.

Beyond that, it’s important to keep photos in the order in which they were originally stored. Photos derive some of their context from their relationship to other photos around them, be there prints in an envelope or digital images in a web gallery.

It is not always practical to include every photo in the collection as the cost of digitisation and cataloguing pre-digital photos can be significant. These decisions need to be based on knowledge of the needs of current users, and our best estimation of the needs of future users. Archivists need to strive to cultural impartiality in these decisions lest photos of future interest be inadvertently discarded as being of little value.

These decisions are not always easy, but they are worth the effort as preservation of the past represents cultural memory of the community.

![]()

Hugh Thomas, Archives Intern, City of Parramatta, Parramatta Heritage Centre, 2019

References

[1] Millar, L. A. (2017). Archives: principles and practices: Facet Publishing, p. 16

[2] Millar, L. A. (2017). Archives: principles and practices: Facet Publishing, p. 7

[3] Bettington, J., Eberhard, K., Loo, R., & Smith, C. (2008). Keeping archives: Australian Society of Archivists Incorporated, p. 253

[4] Stevens-Rayburn, S., & Boulton, E. N. (1998). “If it’s not on the Web, it doesn’t exist at all”: Electronic Information Resources–Myth and Reality. Library and information Services in Astronomy III, 153, p. 196

[5] Nesmith, T. (2006). The concept of societal provenance and records of nineteenth-century Aboriginal-European relations in western Canada: Implications for archival theory and practice. Archival Science, 6(3-4), p. 352