Pemulwuy, an Aboriginal warrior was born into the 'woods tribes' or Bediagal (Bidjigal) clan around 1750, on the northern side of what we now know as the Georges River, Botany Bay. His name is spelt as Pemulwhy, Pemulwoy and Pemulwuy. Also, Bimblewove, Bumbleway and Pimbloy; derived from the Darug (Dharug) word pemul, meaning earth or clay.

Pemulwuy suffered a lasting injury to his left foot and left eye; his eye barded with red stones fastened with gum tree sap made him appear quite fearsome; despite his injuries, he was a powerful man.

In 1788, almost 1500 Europeans arrived at Australia on the 'First Fleet', bringing with them foreign animals, weaponry, and disease. Indigenous Australians were not happy with the Europeans arrival, their land being plundered for agriculture, among many other intrusions into their life as they knew it, including a deadly outbreak of smallpox in 1789 leading to violence between the indigenous people and the Europeans.

In December 1790, Pemulwuy speared John McIntyre, Governor Phillip's gamekeeper. John later died of the wound. The spear was barbed with small pieces of red stone; it was known to belong to Pemulwuy. John was one of three convicts appointed by Governor Phillip to hunt for game once the settlers’ supplies ran out. He was “feared and hated by the Eora people”. He had allegedly committed such gruesome acts against the Aboriginals that his convict colleagues refused to record them.

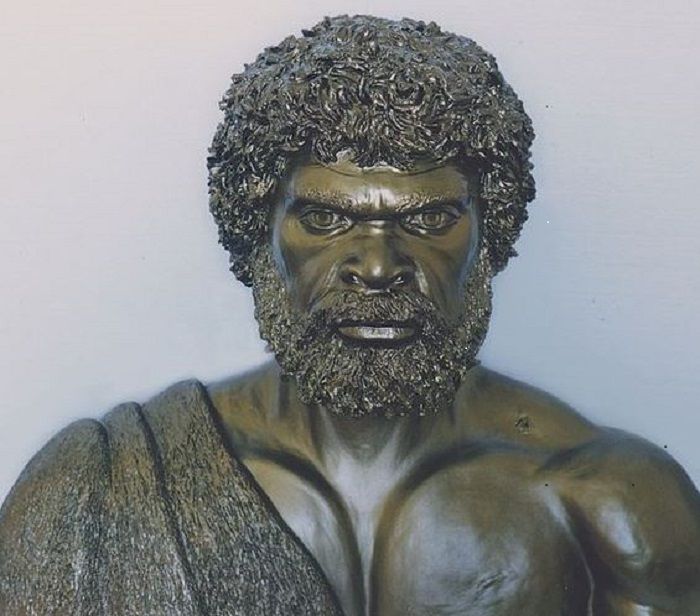

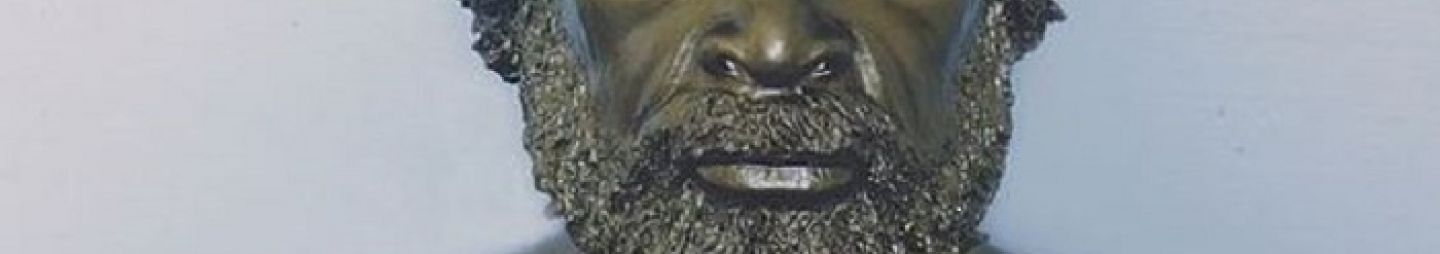

Engraving by Samuel John Neele of James Grant’s image of ‘Pimbloy’, believed to be the only known depiction of Pemulwuy (Image source: https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/pemulwuy)

Pemulwuy led raids on settlers at Brickfield Hill, Georges River, Hawkesbury River, Parramatta, Prospect and Toongabbie from 1792. In December 1793, David Collins, deputy judge advocate and lieutenant governor, reported an attack by Aboriginals who were of the Hunter's or Woodman's tribe, people who seldom came among us, and who were not well known'. David also reported that 'Pe-mul-wy’, a wood native, and many strangers, came in' to an initiation ceremony held at yoo-lahng (Farm Cove) on 25 January 1795. David thought Pemulwuy, as a ‘most active enemy to the settlers, plundering them of their property, and endangering their personal safety’. Raids were made for food - particularly corn, or as a 'payback' for atrocities. David suggested that most of these attacks by Aboriginals were the result of the settlers 'own misconduct', including the kidnapping of Aboriginal children.

The Battle of Parramatta - Peaceful diplomacy could not be achieved between the settlers and Pemulwuy. Captain Paterson, a soldier, explorer and lieutenant governor directed that soldiers be sent from Parramatta to check 'these dangerous depredators'. Military force was used against Pemulwuy and his people.

Pemulwuy simply did not want settlers on his land and so the violence continued. Pemulwuy led a violent revolt against their settlement through multiple attacks - he attacked settlers, burned their huts, speared cattle and destroyed crops.

In March 1797, Pemulwuy led a raid on the government farm at Toongabbie. Settlers formed a punitive party and tracked him to the outskirts of Parramatta. During this attack, Pemulwuy was wounded by seven pieces of buckshot to the head and body. He was taken to the hospital but managed to escape despite having an iron around his leg.

As Governor John Hunter said in 1798:

“A strange idea was found to prevail among the natives respecting the savage Pe-mul-way, which was very likely to prove fatal to him in the end. Both he and they entertained an opinion, that, from his having been frequently wounded, he could not be killed by our fire-arms.”

Governor Philip King, however, intended to prove that theory wrong. He offered rewards for the warrior’s death or capture. Some of these rewards included 20 gallons of rum and two pairs of clothes just for any information. Despite this, even the governor had to admire Pemulwuy’s spirit. Pemulwuy was “a terrible pest to the colony,” the governor wrote, but “he was a brave and independent character.”

Indeed, Pemulwuy was such an impassioned fighter that he even convinced some convicts of the penal colony to fight along with him.

The Death of Pemulwuy – On 2 June 1802, Pemulwuy was shot dead by Henry Hacking. George Suttor described the subsequent events: 'his head was cut off, which was, I believe, sent to England'. Pemulwuy’s head was believed to be stored in the collection of well-known scientist Sir Joseph Banks and for a time in the 19th century, the head remained at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, but it has since been lost. During Prince William’s visit to Sydney in 2010, Indigenous Australians approached Prince William advocating for its discovery and return to Australia.

He was wounded in battle, but he never gave up.

He was shot and captured but he never gave up.

He was shackled in chains, but he never gave up.

With shackles still on his feet, he re-joined the fight.

Pemulwuy never gave up.

M. Marjanovich

‘Members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are advised that the this article contains images, names and stories of deceased peoples.’

![]()

Neera Sahni, Research Services Leader, Parramatta Heritage Centre, City of Parramatta, 2020

References:

Aborigines (VF00002) retrieved on 20/12/2017 from Heritage Centre Research Library Vertical Files collection.

Ancestry.com. New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary's Papers, 1788-1856 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010.

Bladen, F.M. (1979). Historical records of New South Wales. (Volume 4 Hunter & King 1880-1802). Mona Vale, NSW: Landsdown Slattery & Company. Attached file

Brook, J., & Kohen, L. (1991). The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black town: a history. Kensington, NSW: UNSW Press.

City of Sydney & Sydney Barani. (n.d.). ‘Pemulwuy’, Barani: Sydney’s Aboriginal History. Retrieved from http://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/pemulwuy/

Flynn, M. (1995). Place of eels : Parramatta and the Aboriginal clans of the Sydney Region: 1788-1845. Parramatta, NSW: Form Architects. Attached file

Goodall, H. & Cadzow, A. (2009). Rivers and resilience : Aboriginal people on Sydney’s Georges River, Sydney, NSW: UNSW Press.

Horton, D. (Ed.). (1994). The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history, society and culture. (Volume 2). Melbourne, Victoria: Aboriginal Studies Press. Attached file

Kohen, J. L. (2005). 'Pemulwuy (1750–1802)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved from http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/pemulwuy-13147/text23797

Lim, J. (2016). The Battle of Parramatta : 21 to 22 March 1797. North Melbourne, Victoria: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

National Museum Australia. (n.d.). ‘Pemulwuy’, Defining moments in Australian history. Retrieved from http://www.nma.gov.au/online_features/defining_moments/featured/pemulwuy

National Museum Australia. (2015). ‘Transcripts of speeches from the unveiling of the Pemulwuy plaque’, Defining moments in Australian history. Retrieved from http://www.nma.gov.au/online_features/defining_moments/about/commemorative_plaques/transcripts_from_unveiling_of_pemulwuy_plaque#fullspeech

‘Pemulwuy’ (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.convictcreations.com/history/pelmulwy.htm

Purvis, C. (2016). The life and legacy of Pemulwuy. SCEGGS Darlinghurst Year 9 Junior Ron Rathbone Local History Prize 2016. Retrieved from https://www.rockdale.nsw.gov.au/library/pages/pdf/RonRathbone2016/purvis_cindy.pdf

Silverman. Leah (2019). Pemulwuy: The ‘troublesome savage’ who led the aborigines against Australia’s colonizers. Retrieved from https://allthatsinteresting.com/pemulwuy

Sonicnomad Vimeo. (2010). Pemulwuy- A War of Two Laws (Part 1) [video file]. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/59533924

Tench, W. (1979). Sydney's first four years: being a reprint of A narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay and, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson. North Sydney, NSW: Royal Australian Historical Society.

Tench, W. (1996). 1788 : Comprising A narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay and A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson.

The Hunter and Collector (Hanks, R. 2010). Retrieved from https://www.nicholasthompsongallery.com.au/artists/rew-hanks/

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842) - https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/

Turbet, P. (2011). First frontier : the occupation of the Sydney region 1788-1816. Dural, NSW: Rosenberg publishing. Attached file

Vincent Smith, K. (2010). ‘Pemulwuy’, Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved from http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/pemulwuy

Whigham, N. (2015, September 12). ‘Despite the efforts of politicians and royalty, the skull of the ‘rainbow warrior’ remains at large’, news.com.au. Retrieved from http://www.news.com.au/technology/science/human-body/despite-the-efforts-of-politicians-and-royalty-the-skull-of-the-rainbow-warrior-remains-at-large/news-story/af34212e27b74b4c7b4b52c3816bad28

Willmot, E. (1988). Pemulwuy: the rainbow warrior. Sydney, NSW: Bantam.

Pemulwuy: The Aboriginal Resistance Leader

Pemulwuy was a Bidjigal man from the Botany Bay area of New South Wales. Born around the 1750s, he became a key figure in the resistance against British settlers from the late 18th century until his death in 1802.

Key Highlights of Pemulwuy's Life:

Resistance Leader: Pemulwuy led a series of guerrilla warfare campaigns against the British settlers, targeting their crops, livestock, and infrastructure.

Symbol of Hope: For the Indigenous Australians, Pemulwuy became a symbol of resistance and hope against the oppressive forces of colonization.

Mystical Figure: There were many stories about Pemulwuy's ability to withstand bullets and his supposed invulnerability. This added to his legendary status among both the Indigenous people and the settlers.

Tragic End: Pemulwuy's life came to a tragic end in 1802 when he was shot and killed. His head was severed and sent to England, a grim testament to the brutalities of colonization.