Aboriginal peoples in the Sydney Basin would have experienced extreme climate change effects around 18,000 years ago as the ice sheets melted and inundated the continental shelf — perhaps forcing a movement westward.

The site known as Darling Mills SF2 at West Pennant Hills to the north-west of Parramatta is a large rock-shelter which, archaeological evidence suggests, was used as a refuge when coastal communities were forced westwards by a sea-level rise of more than 100 metres. At that time, more than 1,000 square kilometres of Sydney was submerged, including the ‘drowned valley’ of the lower Parramatta River, now called Sydney Harbour. [1]

There is considerable evidence of sophisticated environmental management conducted over long periods by Aboriginal people — in particular, fire-stick farming. [2] The First Fleet officer John Hunter noted that Aboriginals around Sydney ‘set the country on fire for several miles extent’. He recognised that the purpose was ‘to clear that part of the country through which they have frequent occasion to travel, of the brush or underwood’, as well as enabling women to get at edible roots with digging sticks. The mosaic of landscapes in Sydney was ‘maintained by Aboriginal burning, a carefully calibrated system which kept some areas open while others grew dense and dark’. [3]

Research in the Sydney region suggests an increase in burning in the late-Holocene period. [4] The landscape around Sydney was not a wilderness but cultivated country. In fact, some early settlers ‘found environments which reminded them of the manicured parks of England, with trees well spaced and a grassy understorey’. The country west of Parramatta and Liverpool was described in 1827 as ‘a fine-timbered country, perfectly clear of bush, through which you might, generally speaking, drive a gig in all directions, without any impediment in the shape of rocks, scrubs and close forest’. [5] It is important not to overgeneralize from these accounts or romanticize what were creative curating practices, but it is likely that burning practices were the primary cause of ‘the open environment dominated by well-spaced trees and grass’. [6] With settlement, we know that once Aboriginals stopped these burning practices, understorey species such as Bursaria spinulosa (Christmas Bush) and other small plants thrived, and larger animals that were once common declined or disappeared from the area. [7]

The area now known as Parramatta Park is an important heritage area, containing scarred trees from which bark was removed to make canoes, and water-carriers, shell-middens, and what archaeologists call ‘artefact scatters’ and ‘below-ground deposits’. Parramatta Park has been described as ‘a rare example of an intact Aboriginal cultural landscape within Sydney’. [8] ‘Intact’ is an inappropriate concept here, but resonances of a prior open landscape are certainly apparent. In summary, we can say that the landscape of Parramatta was created and managed over long periods by the Darug peoples using a variety of land management methods.

The Parramatta Domain is a good example of how European settlers and settlements benefitted from the competencies and achievements of Aboriginal peoples. [9] Recent research has focused on the way that Australian urban spaces have built on existing Aboriginal geographies. Thus Kerkhove — drawing on examples from Brisbane — suggests that the location of Aboriginal camps played a pivotal role in ‘defining where and how our towns and suburbs emerged’.

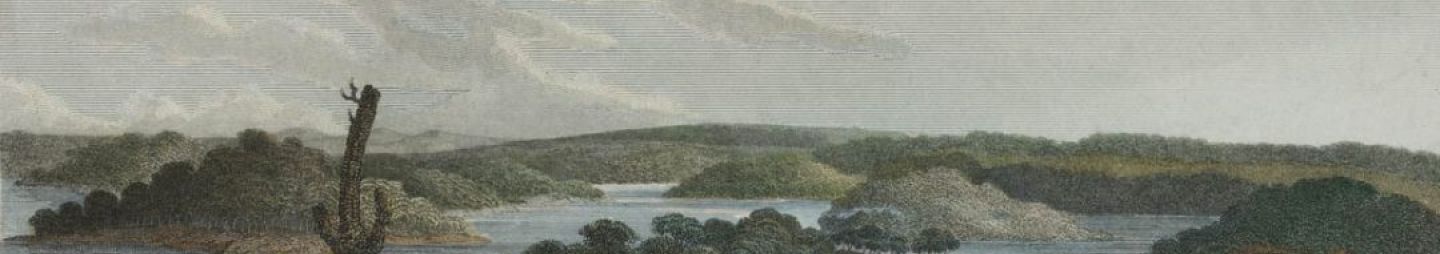

Image: By water to Parramatta, with a distant view of the western mountains, taken from the Windmill-hill at Sydney, 1798. J. Heath. From Dixson Library; State Library of New South Wales.

Phillip Mar and Paul James, Institute for Culture and Society at Western Sydney University (WSU) for the City of Parramatta, Parramatta Heritage Centre, 2017

References

- Comber, J. (2014). Parramatta North Urban Renewal, Cumberland East Precinct and Sports and Leisure Precinct. Aboriginal Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Assessment. Report to Urbangrowth. 2014.

- Gammage, B. (2011). The biggest estate on earth: how Aborigines made Australia. Crows Nest, N.S.W. : Allen & Unwin, p. 39.

- Karskens, G. (2010). The Colony. A History of Early Sydney. (2010 edition). Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin. pp. 46-47.

- Kohen, J. L. (1995). Aboriginal environmental impacts. Kensington: UNSW Press. p. 40.

- Peter Cunningham, cited in Kohen 1995, p. 41.

- Kohen, J. L. (1995). Aboriginal environmental impacts. Kensington: UNSW Press. p. 41

- Kohen, J. L. (1995). Aboriginal environmental impacts. Kensington: UNSW Press. pp. 41-2.

- Comber, J. (2014). Parramatta North Urban Renewal, Cumberland East Precinct and Sports and Leisure Precinct. Aboriginal Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Assessment. Report to Urbangrowth. 2014.p. 45.

- Kerwin, D. (2010). Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading routes: the colonisation of the Australian economic landscape. Brighton [England], Portland [Or.]: Sussex Academic Press.

- Kerkhove, R. (2015). Aboriginal Camps: Foundation of our towns, suburbs and parks? Evidence from South-eastern Queensland. Paper presented at the ‘Foundational History’, Sydney University. Retrieved 17 July, 2017 https://www.academia.edu/13852040/Aboriginal_Camps_Foundation_of_our_towns_and_suburbs_Evidence_from_south-eastern_Queensland