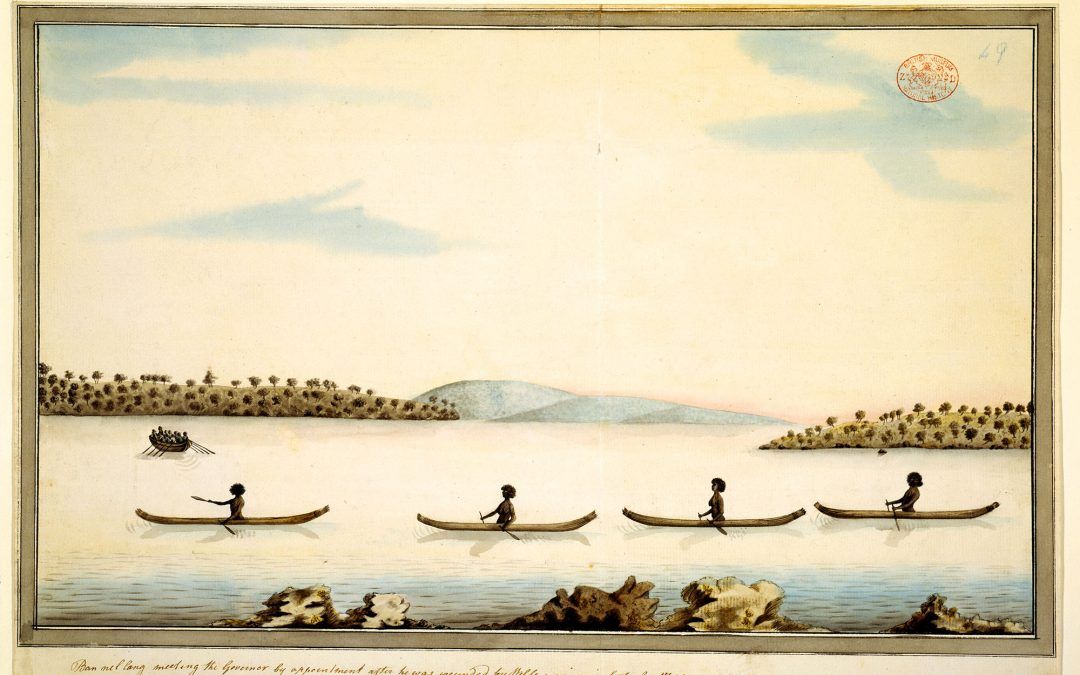

Bannelang [Bennelong] meeting the Governor by appointment after he was wounded by Will [Nille?] ma ring in September 1790. Source: Natural History Museum (London)

Barangaroo was an Aboriginal woman from the area around North Harbour and Manly. She was a member of the Cammeraygal clan, who were considered to be the largest and most influential group of the Eora, the Aboriginal people of the Sydney coastal region [1].

Barangaroo was an influential figure in the early contact between Aboriginal people and the British authorities in the years following the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. Having survived the smallpox epidemic of 1789 that killed her first husband, and it is believed more than half of Sydney’s Aboriginal population [2], she was ‘one of a reduced number of women who had the knowledge of laws, teaching and women’s rituals and she exercised this authority over younger women’ [3].

Barangaroo’s cultural authority came from her role as a fisherwoman [4]. Eora fisherwomen were the main food providers for their families, highly skilled in fishing and canoeing whilst juggling onboard fires and small children in ‘in surf that would terrify their toughest sailors’ [5]. She has described her as:

…Very striking but also a little frightening. She had presence and authority… She was older, more mature, and possessed wisdom, status and influence far beyond the much younger women the officers knew [6].

…Worldly, wise and freer of spirit than the settlers expected of a woman – at least the English women of the time… The colonists observed her to be a determined and persuasive character [7].

Bennelong (left) and Barangaroo (right). Cropped image from painting. Source: Natural History Museum

Barangaroo’s second husband Bennelong (namesake of Bennelong Point where the Sydney Opera House stands), was a Wangal man, who was befriended by Governor Phillip and one of the best known Aboriginal people within the colony at Sydney Cove [8]. However, Barangaroo’s interactions with the British were markedly different to those of Bennelong. The first recorded meeting with British officers occurred in the late 1790s, however, it is also likely that she was present at two earlier meetings between the Cameragal and the British, first at Manly in 1788 and then at an attempted ambush of British men in North Harbour in November 1788 [9].

Barangaroo refused offerings of food and drink from British soldiers and intervened when a convict was being flogged for stealing fishing gear from her clan [10]. She also refused to wear European clothes, the only thing she was ever seen wearing was a slim bone through her nose [11].

Barangaroo also exercised considerable influence over Bennelong and often expressed her unhappiness at Bennelong’s friendliness with Governor Phillip and the British. She intervened to prevent him from visiting them on a number of occasions. [12]

In 1791 Barangaroo gave birth to a baby girl. She refused Bennelong’s suggestion of giving birth in government house and instead gave birth alone in the bush, sustaining her connection to the land and according to her traditions. Barangaroo died shortly after giving birth. She was cremated, with her fishing gear, and Bennelong spread her ashes in the garden of Government house. [13]

In 2006, the north-east precinct of Darling Harbour was named Barangaroo, in her memory. The recently redeveloped precinct also includes Barangaroo Reserve, Sydney’s newest Harbour foreshore park and Barangaroo ferry terminal connecting it to Parramatta [14]. Barangaroo Reserve was designed with the specific intent of reinvigorating Aboriginal cultural heritage, incorporating structural changes and endemic plant species to reflect the environment as it would have been prior to the arrival of the First Fleet [15].

Today, both Aboriginal history and contemporary culture are celebrated at Barangaroo [16]. In March 2017, an innovative artwork was launched at Barangaroo, a multimedia artwork accessed through an augmented reality app, Barangaroo Ngangamay [17]. Created by Aboriginal artists and curators Amanda Jane Reynolds and Genevieve Grieves in collaboration with local Aboriginal elders, the artwork ‘is designed to give viewers a deeper understanding of the area’s rich Aboriginal history and heritage, and to share the story of Barangaroo, the strong Cammeraygal woman after whom the area is named’ [18].

‘Members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are advised that the this article contains images, names and stories of deceased peoples.’

Chrissie Crispin, Research Assistant – Work placement and Neera Sahni, Research Services Leader, Parramatta Heritage Centre, City of Parramatta 2018

References

[1] Karskens, G. (2014). Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 21/06/18 from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen

[2] Barangaroo Delivery Authority. (2017). Aboriginal culture. The Barangaroo Project. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.barangaroo.com/see-and-do/barangaroo/aboriginal-culture/

[3] Karskens, G. (2014). Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 21/06/18 from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen

[4] Ridgeway, A. (2017). Barangaroo the woman. The Barangaroo Project. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.barangaroo.com/see-and-do/the-stories/barangaroo-the-woman/

[5] Karskens, G. (2014). Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 21/06/18 from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen

[6] Karskens, G. (2014). Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 21/06/18 from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen

[7] Ridgeway, A. (2017). Barangaroo the woman. The Barangaroo Project. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.barangaroo.com/see-and-do/the-stories/barangaroo-the-woman/

[8] Ridgeway, A. (2017). Barangaroo the woman. The Barangaroo Project. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.barangaroo.com/see-and-do/the-stories/barangaroo-the-woman/

[9] Karskens, G. (2014). Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 21/06/18 from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen

[10] Ridgeway, A. (2017). Barangaroo the woman. The Barangaroo Project. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.barangaroo.com/see-and-do/the-stories/barangaroo-the-woman/

[11] Karskens, G. (2014). Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 21/06/18 from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen

[12] Karskens, G. (2014). Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 21/06/18 from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen

[13] Karskens, G. (2014). Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen. Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 21/06/18 from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen

[14] Geographical Names Board. (2015). Barangaroo names assigned. 14 August 2015. NSW: Geographical Names Board, Department of Finance, Services & Innovation. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.gnb.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/204688/GNB_-_Barangaroo_Point_and_Reserve_naming.pdf

[15] Barangaroo Delivery Authority. (2017). Aboriginal culture. The Barangaroo Project. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.barangaroo.com/see-and-do/barangaroo/aboriginal-culture/

[16] Barangaroo Delivery Authority. (2017). Aboriginal culture. The Barangaroo Project. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.barangaroo.com/see-and-do/barangaroo/aboriginal-culture/

[17] Munro. P. (2017). Barangaroo artwork takes Indigenous women into an augmented reality world. Sydney Morning Herald [online]. 10 March 2017. Retrieved from on 21/06/18 from https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/barangaroo-artwork-takes-indigenous-women-into-an-augmented-reality-world-20170309-gutwmv.html

[18] Barangaroo Ngangamay. The Barangaroo Project. Retrieved 21/06/18 from http://www.barangaroo.com/the-project/arts-and-public-program/artistic-associates/barangaroo-ngangamay/