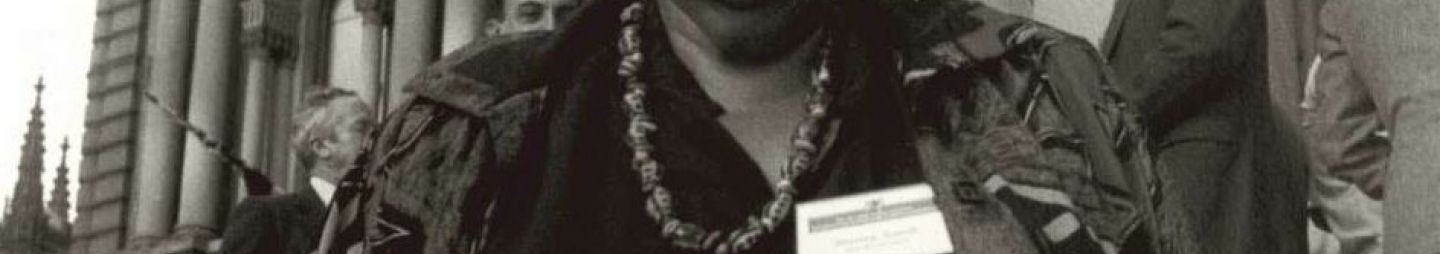

Mum Shirl (Mrs Shirley Smith), Town Hall, Sydney, 1988. Source: National Library of Australia

Shirley Smith (better known as ‘Mum Shirl’), an Aboriginal woman of Wiradjuri descent, was born Shirley Colleen Perry on Erambie Reserve in Cowra on 21 November 1924 [1].

During her early years, Shirley’s parents, Isabel and Joseph Perry spent time working as drovers in nearby Grenfell and her father was also one of the Aboriginal councilors at the Erambie mission. Shirley was also very close to her grandfather, Daniel Boney, who she described as ‘a calm and wise man, who had ethereal connection with the country.’ [2].

When Shirley was six, her grandfather was expelled from Erambie and Shirley moved with her grandparents, to Cowra, where her grandfather and his brother built a house under a railway bridge, ‘Ryan’s place’. At some point they moved to Waterloo in Sydney, but her grandfather didn’t like it and returned to Cowra. Her father continued living and working at Erambie to advocate for the Aboriginal residents of the mission [3].

Shirley had epilepsy and, when she was younger, there was no medication for the illness. Her seizures were a cause of significant stress for her and those around her and she was very grateful to people who cared for her when she had fits. She felt that this was one of the reasons she developed such a strong sense of responsibility to care for others. As a young adult she received treatment for the illness, but it continued to affect her greatly throughout her life [4].

Shirley attended the Erambie Mission School and later, occasionally, St Brigid’s School but her formal education was impaired by her epilepsy [5]. Instead she was taught by her grandfather and it is said she had a ‘prodigious memory and lively wit’ [6] and whilst she couldn’t read or write in English, she learned to speak 16 different Aboriginal languages. [7].

At sixteen, Shirley met Cecil Hazil a professional boxer who was known by his fighting name, Darcy Smith. They were soon married and moved to a house in Surry Hills furnished by Darcy’s manager. Shirley’s first child died in childbirth when Shirley had an epileptic fit. During her second pregnancy she moved to Kempsey on the North coast of NSW to live with her husband’s family, but returned to Sydney when she found that the local hospital was segregated. Darcy spent a lot of time away touring and later returned to Kempsey. Shirley gave birth to a daughter Beatrice and, with family support, raised Beatrice independently until she was three, at which time she placed her daughter in the care of her mother-in-law in Kempsey [8].

When her brother Laurie went to prison, Shirley visited him regularly and when he was released she continued to visit other prisoners. This was both the origin of her nickname, which arose from her being questioned about her relationship with different prisoners – she would always reply, ‘I’m his mum’. It was also the beginning of her lifelong community work. The value of her work was recognized by the authorities, first in the prisons and then later the Child Welfare Department and Newtown police station – who came to rely on her support [9].

Shirley found it difficult to secure stable paid employment with her epilepsy but worked for a time at Argent’s Box Factory and later was paid in her role with the Aboriginal Medical Service. She mostly relied on the pension for income, which she also used to support others, meaning that money was always limited [10]. Shirley worked tirelessly in her community work, including renting houses in Redfern and Surry Hills and caring for many people arriving in Sydney with no friends or family. By the early 1990s she had reared over 60 children [11].

In the 1970s she became actively involved in Aboriginal land rights movement. Shirley travelled to the Northern Territory several times and met with Aboriginal elders such as Vincent Lingiari and Claude Narjic [12]. She was a ‘guiding force’ alongside other Sydney-based Aboriginal activists, including Ken Brindle and Chicka and Elsa Dixon in the Gurindji campaign for land rights. With this same group, Shirley also helped establish the Aboriginal Legal Service in 1971, the Aboriginal Medical Service in 1972, the Aboriginal Black Theatre, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, the Aboriginal Children’s Service, the Aboriginal Housing Company and the Detoxification Centre at Wiseman’s Ferry [13].

Through her growing political involvement, Shirley came to understand and appreciate democratic processes and in the 1972 election campaign publicly expressed her support for the Australian Labor Party, including speaking alongside Gough Whitlam at a campaign event [14].

Catholicism also played an important role in her life. At Erambie, a mission where all the residents were (at least superficially) Roman Catholics, her mum was known as the ‘Mad Roaming Catholic’ who found her religion ‘a source of consolation in a harsh world’. Shirley abandoned the Catholic Church for fourteen years after being the subject of discrimination by a Grafton priest during Mass. However, she maintained her Christian beliefs and was particularly influenced by St. Martin de Pourre, a Dominican priest from Peru. She later returned to the church community in an active role, including as an adviser to the Cardinal of the Archdiocese of Sydney, who sponsored her first visit to Darwin in the late 1960s [15].

In 1979 Shirley was awarded Parent of the Year, an Order of Australia and an Order of the British Empire. In 1981 she published an autobiography, Mum Shirl, with the assistance of Bobbi Sykes [16].

Shirley died on 28 April 1998, aged 73, and her funeral was held at St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney [17].

‘Members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are advised that the this article contains images, names and stories of deceased peoples.’

Chrissie Crispin, Research Assistant – Work placement and Neera Sahni, Research Services Leader, City of Parramatta 2018

References

[1] Foley, G. (ed.). (1998). Heroes of the Indigenous Resistance. ATSIC News. Kooriweb. Retrieved on 20/06/18 from: http://church-mouse.lanuera.com/mumshirl/ID_Freedomfighter5_Lw414.html

[2] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401.

[3] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401

[4] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401

[5] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401

[6] Foley, G. (ed.). (1998). Heroes of the Indigenous Resistance. ATSIC News. Kooriweb. Retrieved on 20/06/18 from: http://church-mouse.lanuera.com/mumshirl/ID_Freedomfighter5_Lw414.html

[7] Education Services Australia. (n.d.). Shirley Smith (‘Mum Shirl’). Gallery of Australian Biographies. Education Services Australia. Retrieved on 20/06/18 from http://www.civicsandcitizenship.edu.au/cce/smiths,34823.html

[8] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401

[9] Foley, G. (ed.). (1998). Heroes of the Indigenous Resistance. ATSIC News. Kooriweb. Retrieved on 20/06/18 from: http://church-mouse.lanuera.com/mumshirl/ID_Freedomfighter5_Lw414.html

[10] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401

[11] Foley, G. (ed.). (1998). Heroes of the Indigenous Resistance. ATSIC News. Kooriweb. Retrieved on 20/06/18 from: http://church-mouse.lanuera.com/mumshirl/ID_Freedomfighter5_Lw414.html

[12] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401

[13] Foley, G. (ed.). (1998). Heroes of the Indigenous Resistance. ATSIC News. Kooriweb. Retrieved on 20/06/18 from: http://church-mouse.lanuera.com/mumshirl/ID_Freedomfighter5_Lw414.html

[14] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401

[15] Australian National University. (n.d.). Smith, Shirley Coleen (Mum Shirl) (1921–1998). Indigenous Australia. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved on 16/06/18 from http://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/smith-shirley-coleen-mum-shirl-17817/text29401

[16] National Museum of Australia. (n.d.). Shirley Smith (1924 to 1998). Collaborating for Indigenous Rights. National Museum of Australia. Retrieved on 20/06/18 from http://indigenousrights.net.au/people/pagination/shirley_smith

[17] Heiss, A. (2013). Aboriginal involvement with the church. Barani Sydney’s Aboriginal History. City of Sydney. Retrieved on 20/06/18 from http://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/aboriginal-involvement-with-the-church/

- Log in to post comments