The Darug people

The Darug people, who are also referred to as the Dharruk, Dharung, Dharrook, Darrook, Dharug and the Broken Bay tribe, are the traditional owners of the Rydalmere area [1]. The Darug nation spans from Broken Bay to the northeast, the lower Blue Mountains to the west, the Southern Highlands to the southwest and the Illawarra to the southeast. John McClymont relates that “the traditional landowners, the Darug speaking Aboriginal Wallumetta clan, had subsisted for hundreds of centuries along the northern banks and hinterland of the Parramatta river… The clan ranged westward as far as the Subiaco and Vineyard Creeks where the Wallumettagal held corroborees on land granted to Phillip Schaeffer.”

For further information on the Darug people and the Wallumetta and Burramattagal clans visit the website of the Darug Tribal Aboriginal Corporation [2], or read Christopher Tobin’s The Dharug Story [3].

European History

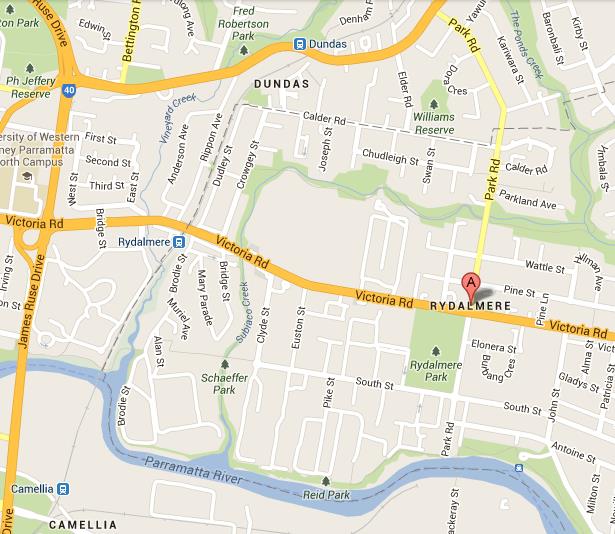

Modern map of the suburb of Rydalmere

The Vineyard Estate, later named Subiaco, existed between Subiaco Creek, Victoria Road, Vineyard Creek and the Parramatta River. This area is now owned by Rheem Australia Pty Ltd. and is utilised for heavy industry.

Phillip Schaeffer

In 1788 Governor Phillip began to establish a settlement at what is now Parramatta and in 1792 he granted 140 acres of land to Phillip Schaeffer on the north bank of the Parramatta River. Schaffer was born in Hesse, Germany, c. 1750 and migrated to Australia as a free man in 1788 [4]. One of many Hessian auxiliary riflemen hired by the British to bolster numbers during the American War of independence, Flynn states that Schaffer’s passage to Australia was most likely the result of a relationship formed with a British official (perhaps based in NSW) during his time of service [5]. Employed as an overseer of convicts it was soon apparent that Schaeffer’s lack of English made it difficult for him to undertake the task he had been employed to manage. This is reflected in a letter written to Governor Phillip where he states “he was not calculated for the employment for which he came out, but as a settler will be a useful man” [6].

Schaeffer’s land bounded Vineyard Creek to the west and Schaffers Creek, later known as Subiaco Creek, to the east [8]. A rough track utilised by settlers of ‘The Ponds’ near todays Ponds Creek, developed to the north of Schaffers land. This later became known as ‘The High Road’, today’s Kissing Point Road.

John McClymont relates that in 1792, alongside the house provided by the government, Schaeffer built a large brick house on the property, planted 1000 grapevines and named the area ‘The Vineyard’ [9]. An article in The Cumberland Argus dated 11/1/1961 relates, “A stone Cottage, built before 1800 by the original grantee, a superintendent of convicts with the First Fleet still stands in the grounds at Subiaco. The cottage is regarded as one of the oldest domestic buildings still standing in Australia” [10]. These buildings were destroyed in 1961 when the company Rheem’s bought and redeveloped the area as an industrial site.

Captain Waterhouse

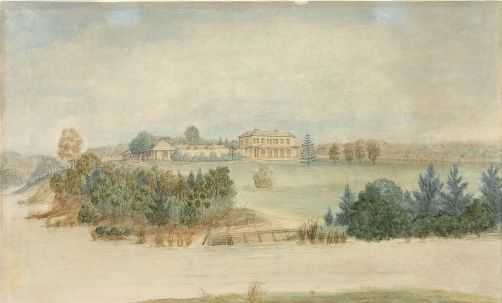

The painting below titled ‘Captain Waterhouse’s house’ depicts a simple, single storey, house in an idyllic setting next to a river, presumably the Parramatta River.

Captain Waterhouse is renowned as the first person to bring merino sheep to NSW [12]. McClymont writes that Waterhouse had worked as midshipman on the First Fleet under Governor Phillip and that he had later been made captain of HMS Reliance. In June 1797 Waterhouse bought a flock of pure bred Spanish merino sheep from the Cape of Good Hope to Australia on the Reliance and in August that year he acquired The Vineyard and introduced his new flock to the estate.

Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur

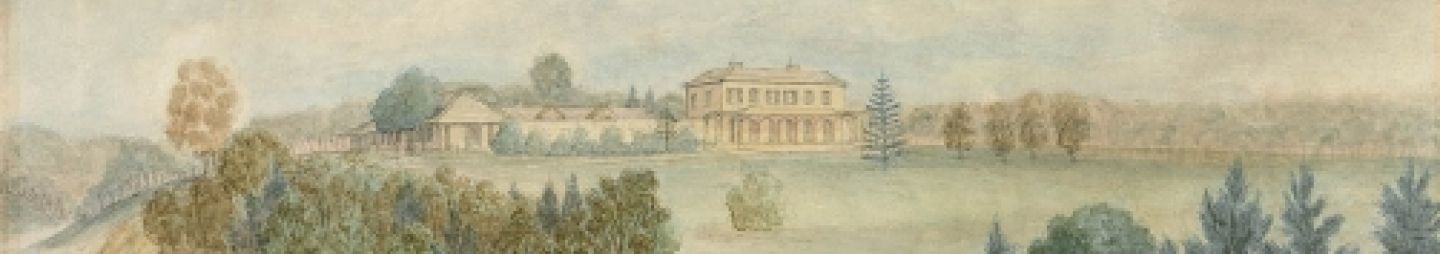

In 1813 the property was sold to Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur (nephew of John Macarthur). Macarthur lived at The Vineyard between 1814 – 1849. The images below reveal the estate as it would have been before Macarthur embarked on the building of the grand manor designed by architect John Verge.

![Details from A survey of Port Jackson, New South Wales, John Septimus Roe, Lieut. R.N., 1822, National Library of Australia, [14].](/sites/phh/files/wp-images/2013/11/portjackson.jpg)

Details from A survey of Port Jackson, New South Wales, John Septimus Roe, Lieut. R.N., 1822, National Library of Australia [14].

The image bellow, drawn by Annie Macarthur, reveals the estate as it would have been when Hannibal Macarthur acquired it from Waterhouse.

The two-storey building of Georgian Regency design was set up against the existing buildings on the site by Verge and was regarded as one of the grandest mansions in the colony at that time [16]. The building was specifically noted for its semicircular geometric staircase (hewn out of three pieces of stone from the estate) and its Doric colonnade [17]. The drawing at the top of this page depicts the original cottage at Vineyard as well as the house built by John Verge for Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur in 1836.

R. J. Polding

![The Most Reverend John Bede Polding O.S.B., first Archbishop of Sydney, Sadd, H. S. (Henry Samuel), c. 1811-1891. Published by Thomas Shine, 1891.[19]](/sites/phh/files/wp-images/2013/11/polding-01.jpg)

The Most Reverend John Bede Polding O.S.B., first Archbishop of Sydney, Sadd, H. S. (Henry Samuel), c. 1811-1891. Published by Thomas Shine, 1891 [18]

Although New South Wales remained a penal colony, with convicts contributing to 38% of its total population of 71,662, the effects of parliamentary reform in Britain were still strongly felt [19]. The British government, aware of the advantages of religion for an orderly society, declared additional positions available for representatives from denominations outside that of the Church of England. In 1834 John Bede Polding, who hailed from the upper ranks of English Catholic society, was appointed “vicar-apostolic of New Holland, Van Diemen’s Land and the adjoining islands” [20]. On his notification of Poldings appointment in 1835 Governor Sir Richard Bourke declared that ‘it is very desirable that Dr Polding should be enabled to exercise a salutary influence over the Roman Catholic chaplains’ [21]. Though Polding did not owe his position to the British government, he had its approval and was paid from public funds, factors that greatly influenced the course of his term.

In 1849 Polding, who had become an Archbishop, purchased the Vineyard Estate on the Parramatta River from Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur, renaming it Subiaco, after the site near Rome where St Benedict had retired to meditate [22]. He established a Benedictine Convent in the two-storey building designed by Verge and from 1851 the convent functioned as a school for girls teaching “young ladies in piety and learning… with tuition in English, French, Writing and Arithmetic” [23].

It is unclear exactly when Rydalmere became a Catholic parish however the church and school at Subiaco were blessed on the 18 September 1889 by Cardinal Moran and Reverend Ed Kearney became pastor from this time on [24]. The nearby Hospital for the Insane, visible in the image below, also lay under Kearney’s domain and in 1912, 360 of the 672 Catholics in the area came from the hospital [25].

The nuns earned a living through the provision of the school for girls and during World war One, by making Altar Breads for the Army Chaplains with the Australian and American Troops. However with the growth in state and private schools the number of pupils at the school declined and the order became a closed Benedictine community. The convent struggled financially after this time and survived by selling of parcels of the estate until 1957, when the area around Subiaco (Rydalmere) was claimed for industry.

![H.W. Horning & Co., Rydalmere Station Estate: auction sale on the ground, Sat. 2nd March 1918 at 3 p.m., 1918.[30]](/sites/phh/files/wp-images/2013/11/subiaco-estate-division.jpg)

H.W. Horning & Co., Rydalmere Station Estate: auction sale on the ground, Sat. 2nd March 1918 at 3 p.m., 1918 [26]

The nuns moved to a new Monastery in Franklin Road, West Pennant Hills, and lived there until 1988, when suburbia encroached to the extent that monastic life was affected negatively. They then moved to a property on the Jamberoo Mountain Pass, in the Illawarra and the convent exists there top this day.

Rheem Australia Pty Ltd.

Much of Rydalmere was still farmland before World War II, the 1930s depression having destroyed grand schemes for suburban subdivision, however the area’s waterfront and rail connection had begun to attract heavy industry and development accelerated in the post war era. State planners designated Parramatta as a growth centre, and sections of Rydalmere were zoned as industrial land. By the 1950s, Rydalmere factories were producing goods such as steel and concrete pipes, hot water systems and earth-moving equipment. In 1961 Rheem Australia Pty Ltd. bought the remaining three acres of the estate and the buildings, including the grand house designed by Verge were destroyed in order to build factory warehouses and a car park.

The colonnade was dismantled and gifted to the University of New South Wales and now exists along the main university walkway on Sciences Road. Other parts of the building were also taken and preserved. The cantilevered staircase was donated to the National Trust, who had fought desperately for the preservation of the building.

![]()

Rebecca Anderson, Museum and Heritage Consultant, Parramatta Council Heritage Centre, 2013

References

Australasian Chronicle (Sydney, NSW : 1839 – 1843), p. 4.

Kass, T., C. Liston and J. McClymont, Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996).

Subiaco (VF01032) Retrieved on 04/08/2013 from Heritage Centre Research Library Vertical Files collection.

Flynn, M. The Second Fleet, Britain’s Grim Armada of 1790, (Sydney: 2001). Britton, A, History of New South Wales From the Records, Volume II (Sydney: Charles Potter, 1894). – A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook, eBook No.: 1204371h.html).

1] http://www.darug.org.au/DarugW.html

[2] http://www.darug.org.au/DarugW.html

[3] http://www.darug.org.au/Darug%20files/STORIES/DARUGSTORY.pdf

[4] M. Flynn, The Second Fleet, Brittan’s Grim Armada of 1790, (Sydney: 2001), p. 9.

[5] Julie McIntyre, Not rich and not British, Philip Schaeffer, ‘Failed’ colonial farmer (Sydney: University of Sydney, 2007), p. 9. http://www.newcastle.edu.au/Resources/Institutes/Humanities%20Research%20Institute/Wine%20Studies/Not%20Rich%20and%20Not%20British.pdf

[6] Phillip to Grenville, 5 November 1791, HRAI, Vol. 1, pp. 271, 279.

[7] Phillip Schaeffer’s land grant, signed on the 22 February 1792 by Governor Arthur Phillip, with signatures of witnesses George Johnston, John Palmer and John White, and signature of David Collins, Secretary. ‘No. 2′ on verso, the second land grant in Australia. The grant is accompanied by a typed statement by W.M. Butler giving a brief history of land transfers up to 1927 when Subiaco Convent occupied part of the land. http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/item/itemDetailPaged.aspx?itemID=455736.

[8] Quoted as “taken from school brochure” – SEW:AW, A brief History: The Site of Rheem Australia Limited Rydalmere, New South Wales, 13 July 1976. Subiaco Subiaco (VF01032) from Heritage Centre Research Library Vertical Files collection.

[9] John McClymont, James Houison 1800 – 1876 Parramatta’s Forgotten Architect (Parramatta: Parramatta and district Historical society Inc., 2010), p. 14.

[10] The Cumberland Argus. Wed. 11/1/1961, Subiaco (VF01032) from Heritage Centre Research Library Vertical Files collection.

[11] Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales – Captain Waterhouse’s house, The Vineyard, c. 1798. http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au//item/itemLarge .aspx?itemID=887728.

[12] SEW:AW, A brief History: The Site of Rheem Australia Limited Rydalmere, New South Wales, 13 July 1976. Subiaco Subiaco (VF01032) from Heritage Centre Research Library Vertical Files collection.

[13] Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales – Portrait of Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur, 1800-1820, http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/item/itemDetailPaged.aspx?itemID=843890

[14] National Library of Australia – Detail from A survey of Port Jackson, New South Wales – 1822, by John Septimus Roe, Lieut. R.N., revealing Schaffer’s Vineyard Cottage. Published in London as part of Charts of the coast of Australia by Phillip Parker King, according to an Act of Parliament at the Hydrographical Office of the Admiralty in 1826 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/10730578?q&versionId=19656018

[15] Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales – Vineyard. N.S. Wales, Annie Macarthur, 1834 http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/item /itemDetailPaged.aspx?itemID=404985. Exhibited in Memory of Trees exhibition – Parramatta Heritage Centre.

[16] John McClymont, James Houison 1800 – 1876 Parramatta’s Forgotten Architect (Parramatta: Parramatta and district Historical society Inc., 2010), p. 21.

[17] John McClymont, James Houison 1800 – 1876 Parramatta’s Forgotten Architect, p. 21.

[18] National Library of Australia – The Most Reverend John Bede Polding O.S.B., first Archbishop of Sydney, Sadd, H. S. (Henry Samuel), c. 1811-1891. Published by Thomas Shine, 1891 http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an9997459 [20] Bede Nairn, Polding, John Bede (1794–1877), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, (MUP), 1967 http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/polding-john-bede-2557.

[19] Nairn, Polding, John Bede (1794–1877), Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1967.

[20] Nairn, Polding, John Bede (1794–1877), Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1967.

[21] Mariana Starke, Travels on the continent https://archive.org/details/travelsoncontin00stargoog/page/n6

[22] John McClymont, James Houison 1800 – 1876 Parramatta’s Forgotten Architect (Parramatta: Parramatta and district Historical society Inc., 2010), p. 25.

[23] http://www.parra.catholic.org.au/about-your-diocese/history/history-of-the-parishes/history-of-the-parishes-in-the-catholic-diocese-of-parramatta.aspx

[24] Bede Nairn, Polding, John Bede (1794–1877), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, (MUP), 1967. Viewed online at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/polding-john-bede-2557

[25] The Subiaco estate remained in the area on this map between Subiaco Creek, the Parramatta River, the Hospital for the a Insane and Victoria Road. http://mapco.net/sydneyhar/sydney08.htm

[26] http://www.nla.gov.au/apps/cdview/?pi=nla.map-lfsp2458-s1-v

![State Library of NSW - Phillip Schaeffer's land grant.[7]](/sites/phh/files/wp-images/2013/11/Schaeffers-Land-Grant-748x1024.jpg)

![Captain Waterhouse's house, The Vineyard, c. 1798. [11]](/sites/phh/files/wp-images/2013/11/Cap-Waterhouse.jpg)

![Portrait of Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur, 1800-1820.[13]](/sites/phh/files/wp-images/2013/11/hanibal-hawkins.jpg)

![Annie Macarthur, Vineyard. N.S. Wales, 1834, State Library of New South Wales [15]](/sites/phh/files/wp-images/2013/11/annie-Mcarthur.jpg)