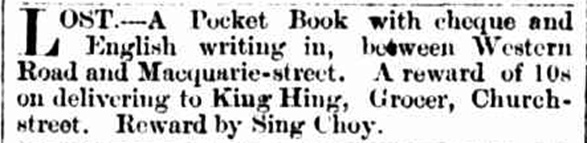

Advertising (1888, October 6). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p. 5. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article86269023 [1]

Sing Choy’s smile and sonorous ‘Good Morning’ was described as ‘a feature of Parramatta town life’. As market gardener and storeman, Choy was well-known in Parramatta, but it was his services as interpreter for the local Chinese community that established his reputation.

Choy makes his mark on Parramatta from the late 1880s up until around 1902. Little, either before or after these dates, is known. There is, for instance, no record (as yet found) of Choy’s arrival in Australia, although a ‘Sing Choy’, aged 28 from Canton, is listed as being the ‘messroom boy’ on the immigrant ship ‘Normanby’, which sailed from Hong Kong via Cooktown for Sydney in 1878. [2]

In 1887, Choy is identified as a tenant of a seven-acre property, listed for sale through John Taylor’s Real Estate Property Rooms, located on Church Street. The property was listed as ‘The Chinamen’s Garden’ and described as:

…enclosed with a paling fence, and cultivated as a Fruit and Vegetable Garden, and occupied by Sing Choy, as tenant, situate with extensive frontages to Church and Bourke streets, Parramatta North, and bounded on the north by Hunt’s Creek, and the late James Pye’s orchard…The soil is excellent (very rich), well-suited for orchard and garden purposes. [3]

Sands Directory 1888

Sing Choy – Market Gardener – Board Street, Parramatta

http://cdn.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/learn/history/archives/sands/1880-1889/1888-part4.pdf

In 1888, the Sands Directory lists Choy as a market gardener of Board Street, Parramatta. By 1890, Choy had relocated from the north to Church Street, where he took up as a green grocer. Choy had relocated to premises on George Street by 1892, where an incident involving fireworks, the fire brigade, and ruined bacon is recorded. [4]

The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate reports the incident as occurring at around 7:30 in the evening on Monday, 16th May, 1892. Sing Choy and some companions, described by the paper as ‘Celestial brethren’, were letting off fireworks at the rear of the premise, when a rocket had the misfortune to land on the ‘shingle roof’ of a shed located next door in Mr Henry Colley’s sale yards. Neighbours, as well as both the No. 1 and No. 2 Fire Brigade attended the scene, and although the fire was quickly extinguished with only ‘trifling’ damage, ten pounds of bacon and dairy produce were destroyed. The paper suggests that ‘it is probable that Sing Choy will be called upon to make good the damage’, while the Fire Brigade urged members of the public to avoid the use of fireworks, despite their attractiveness. Sing Choy’s ‘display’, they declared, was evidence of the damage to property that could occur. [5]

Delving into Choy’s life provides insight into the physical violence Chinese migrants experienced in the community. In 1889, Choy appeared before the Parramatta Police Court to provide a deposition for a trial brought by Ah Wong against J. Burke, C. Watts, R. Small and E. Sonter. Ah Wong’s case was that he had been physically assaulted by the defendants while they were all engaged in dam-making at Mr. Neale’s Field of Mars property. Choy deposed that:

…on the day in question he saw complainant whose face was swollen as from a blow; he went and remonstrated with defendant Burke and told him he might have killed complainant; Burke replied that he didn’t care; he also saw Small who told him it was all done in fun. [6]

The Bench ‘had no doubt an assault had been committed’, describing the incident as ‘another instance of the larrikinism of the day’ and fined and imprisoned the defendants.

Choy himself was also the victim of violent attacks. In 1893 he was subject to an attack described by the Cumberland Argus as ‘dastardly’. At around 3:30 pm on the 27th January, Choy was ‘set upon’ by three ‘larrikins’. The attackers threw stones at Choy’s horse, resulting in cuts to the animal, and took to Choy’s cart with palings. Choy ‘showed fight’, causing the ‘cowardly skunks’ to flee. It was anticipated that that ‘dastards’ would be recognised and brought to justice. Another incident occurred in March, 1901, in which Arthur Sallaway was charged with and found guilty of, throwing stones at Choy. The defendant ‘flung a stone’ which hit Choy in the back, while other ‘young men’ who were present threw a ‘shower of stones’ that was ‘like a hail storm’. [7]

It is through Choy’s role as an interpreter, however, that history records his impact on Parramatta, and his role in the lives of members of the Chinese community. In 1895, Choy acted as an interpreter for Willie Ah Poo, charged with using water for other than domestic purposes. The case was withdrawn after the defendant agreed to pay costs. In March, 1897, Choy acted as interpreter for two Chinese men charged with invading the persimmon and lemon orchards of Messrs. Iredale and Batchelor. In this case, both defendants were imprisoned for three months, in a determination to ‘put down fruit-stealing’. Mr Batchelor’s citron orchards were the focus of another case in April 1897, where Choy acted as interpreter for Jim Egg and Ah Fook. In August 1897, Ah Sam pleaded guilty to the assault of John Finlayson, through Choy as interpreter and in 1900 Choy acted as interpreter for Boo Hop, who defended a charge brought against him by H.W. Runge of damage to a bicycle through negligence. [8]

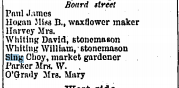

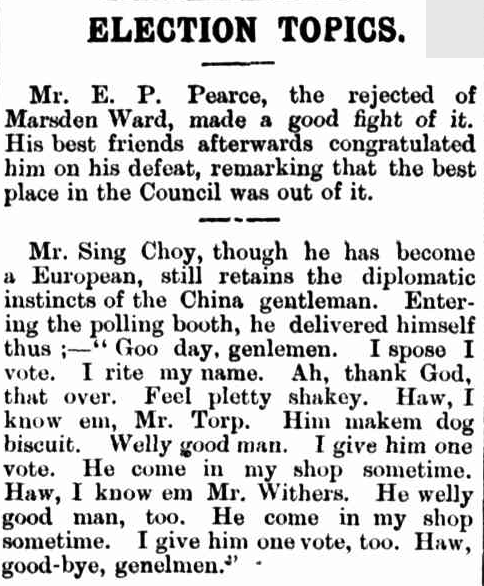

Choy appears to have acted as a conduit between the Chinese and European communities. The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, for example, records Choy as assisting two other Chinese men to vote. When Ah Low discovered Foo Kay unresponsive in the house they shared, Low went to Choy for help. [9] Choy was able to secure the assistance of the police. He was also able to provide vital information – Foo Kay, Choy deposed, was a very quiet, temperate man, without friends or relatives. [10] Indeed, in the case of the sudden death of Poy Lee, Choy was able to inform the authorities that Lee was 57 years old, from Canton with a wife in China. Choy is recorded as acting as an arbitrator in a damages case between a Chinese market gardener and the Sydney Meat Works. [11] He also acted on behalf of 18 Chinese men who required assistance to register the death of Sun Quoy and to obtain a burial permit. [12]

Election topics. (1898, February 12). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p. 3. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85844941 [13]

These newspaper articles also provide glimpses of Chinese culture in Parramatta in the late 1800s. Choy is described on several occasions as swearing an oath in court by ‘blowing out a match’. Paul R. Katz suggests that similar oath taking is recorded in other district courts around the same period. An account of Choy acting as ‘Master of Ceremonies’ at the burial of Ah Cheong provides insight, from a European perspective, of traditional Chinese burials conducted at Rookwood:

There were three Chinese burials, the first being that of Ah Cheong, for some time a resident of Parramatta. The event occasioned much curiosity in George-street, from whence the body was removed, and every cab that was available in the town was fired to convey deceased’s countrymen to the cemetery, and a large crowd of other people journeyed to Rookwood to witness what turned out to be a novel sight. Deceased, although a poor man, had well to do relatives in Sydney and these were present to perform the last rites. The other visitors included two real Chinese women, wives of Sydney merchants. The usual interesting – but to Europeans incomprehensible – ceremony of lighting a big fire in the mortuary furnace and burning messages to joss, besides letting off fireworks to frighten away the devil, were watch with interest. Sing Choy seemed to be Master of Ceremonies. Squibs were stuck round the grave and fired all the time the grave was being filled in, and the feasting and drinking went on meanwhile. [14]

Neera Sahni, Research Services Leader, City of Parramatta, Parramatta Heritage Centre, 2018

References:

[1] Advertising (1888, October 6). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p5. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article86269023

[2] Brook, J. (2010). From Canton with courage: Parramatta and beyond. Chinese arrivals 1800-1900. Jack Brook, Sydney, N.S.W.

[3] Advertising (1887, March 26). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842 – 1954), p 19. Retrived on 05/02/2018 from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13630215

[4] Sands Directory , Retrieved on 25/01/2017 from http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/learn/search-our-collections/sands-directory/1880-1889

[5] Current news. (1892, May 21). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p 4. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article86266876

[6] Parramatta Police Court. (1889, November 16). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p 8. Retrieved on 02/02/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article86268230

[7] Current news. (1893, February 4). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85647385

[8] Brevities. (1895, October 26). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p 1. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-articlpooe85653703

[9] An opium-smoker’s end. (1900, June 6). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p 2. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85821269

[10] Death of a Chinaman. (1897, May 15). The Cumberland Free Press, p 7. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article144440469

[11] Local and district items. (1897, June 26). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p. 2. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85765443

[12] Death of a Chinaman. (1897, May 15). The Cumberland Free Press, p 7. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article144440469

[13] Election topics. (1898, February 12). The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, p 3. Retrieved on 25/01/2018 from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85844941

[14] Divine Justice: religion and the development of a Chinese Legal culture – Paul R. Katz. P 132. Retrieved on 02/02/2018 from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=cczKnfHbkY0C&pg=PA134&lpg=PA134&dq=sworn+in+by+blowing+out+a+match&source=bl&ots=xwaZNC8mAw&sig=mJxnA4egPQw6_9bmawQXaO03XV4&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiDwYrqzobRAhUDF5QKHTuYD6YQ6AEIGzAA#v=onepage&q=sworn%20in%20by%20blowing%20out%20a%20match&f=false