Virtual tour transcript

Written in the Stars: Astronomy in Parramatta

[Title page]

[Image – Australian Night skies]

[Music 1 - Space]

[Image – Aerials of Parramatta, day and night]

It was in the Western Sydney city of Parramatta that the earliest mapping of the Australian night skies, for scientific endeavour, in a purpose-built astronomical observatory, took place.

[Image – Catalogue of Stars volume]

The resulting observations were recorded and published in 1835 as A catalogue of 7385 stars: chiefly in the southern hemisphere at the observatory at Parramatta, New South Wales. A copy of this very rare and famous book is held in the collections of the Parramatta Heritage Centre.

Set against a turbulent backdrop of insatiable personal ambition and professional conflict, the fascinating story behind this book of stars is one of brilliance of mind, lifelong dedication, and outstanding achievement and ultimately, failure.

The story’s legacy is the establishment of a permanent astronomical observatory in Sydney, Australia in 1857.

[Music – Space fades]

[Music – Birds and space]

[Image – Emu in the stars]

[Image - The Place of Ancestors]

The stars above us are timeless, but those glistening in the Southern night skies above the British colonists when they arrived in New South Wales in 1788 were unfamiliar to them.

Of course, there is a deep interest in night skies across Indigenous cultures and for Aboriginal people throughout Australia, the sky and the earth are intricately linked, providing guiding maps that have allowed seasonal safe travel across country for thousands of years.

Aboriginal Elders of the traditional custodians of the Parramatta area, the Darug people, explain that when looking up at the night sky, their Old People would read the stars to navigate the land when travelling for ceremony and trading. From the moving constellations, they also gleaned knowledge about seasonal changes back on country. This ancient knowledge ensured their long term survival and was interpreted as stories and song lines that were passed on throughout the generations.

[Music – Birds and space fades]

[Image – Dawes’ telescope]

The Southern night skies had been observed by British colonists in Sydney Town as early as 1788, when Lt William Dawes set up a temporary observatory on a location now occupied by one of the southern pillars of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

[Audio 5] However, the purposes of Dawes’ observations were practical, rather than purely scientific. Dawes’ measurements were used to establish the precise geographic location of the settlement at Sydney Cove, to define local time for Sydney Town, and to assist with the surveying of the new colony.

[Image – Governor Brisbane]

[Music 2 – Georgian Gentleman]

However, when Sir Thomas Brisbane, the sixth Governor New South Wales, arrived in 1821 he bought with him an almost obsessive interest in the science of astronomy.

In fact, so well-known was his keen interest in observing and measuring the night skies it is said that when the Duke of Wellington heard of Brisbane’s appointment as Governor he exclaimed exasperatedly

“Good grief, we need someone to govern, not the Heavens, but the Earth!”.

[Music – Georgian Gentleman fades]

[Image – OGH outside]

In the glorious, UNESCO World Heritage-listed Parramatta Park, Australia’s oldest remaining residential building, Old Government House, stands.

[Image – OGH interior]

It was here that Brisbane chose to reside rather than in Sydney Town during his time as Governor.

[Image – Astronomical instrument]

One of the actions Brisbane undertook when he arrived at Old Government House was unpack the astronomical instruments and reference books he had brought with him, half way around the world, on the ship from Britain.

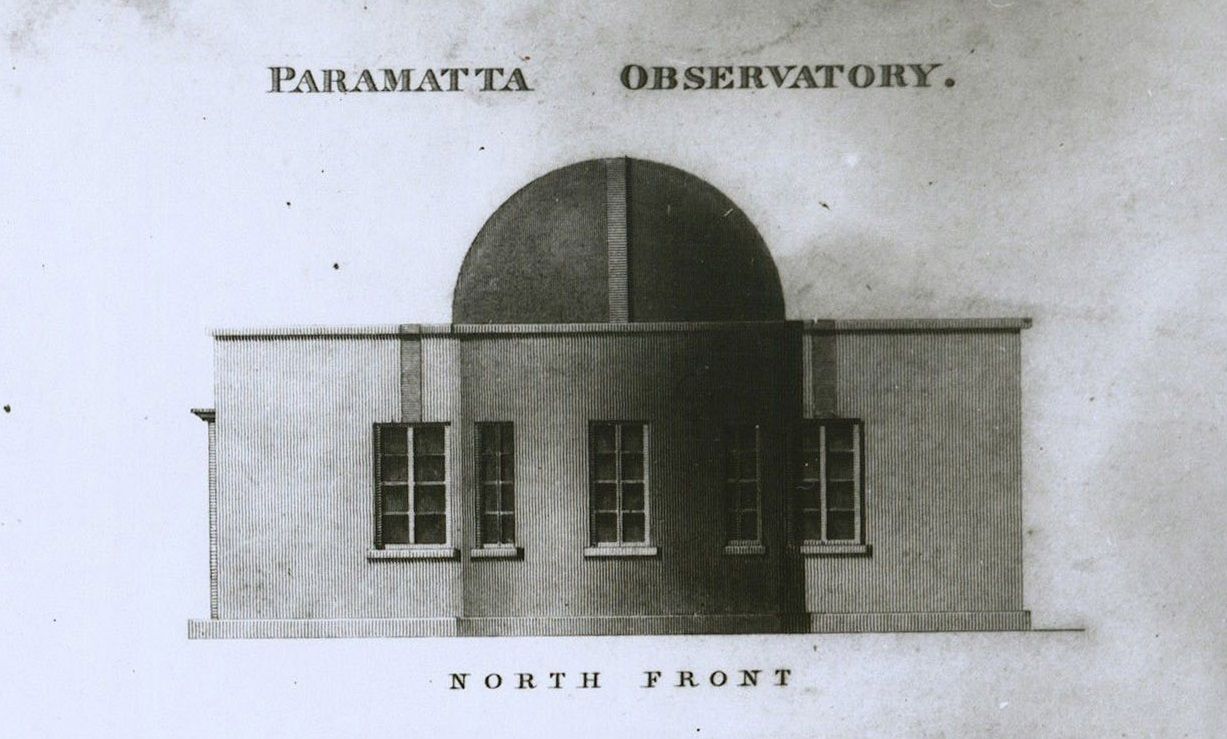

[Image – Sketch of observatory]

Not long after his arrival, Brisbane commissioned the construction of a permanent observatory building, a short distance from Old Government House.

[Image – Plan of observatory]

The observatory was a single storey, timber structure, approximately 9 meters square. It had moveable domes and slits in the walls to enable viewing of the night skies by a refractable transit telescope.

Brisbane employed two astronomers to operative the observatory, Carl Rumker and James Dunlop.

[Image – Carl Rumker]

Rumker was a brilliant, but abrasive and ambitious German scientist,

[Image – James Dunlop]

And James Dunlop was a quiet, studious Scotsman.

[Image – Comet]

Although Rumker, Dunlop and Governor Brisbane had very different personalities, and clashed almost immediately, the observatory quickly came to the attention of the astronomical community when the astronomers recorded the passing of Enke’s comment in June 1822.

[Music – Conflict]

[Image - Rumker]

Despite this early success, following a number of interpersonal disputes between the three men, Rumker abruptly resigned in June 1823.

Then, in December 1824 Governor Brisbane was recalled early to London, thought by some to be due to the excessive time he spent in the observatory.

Having joined Brisbane at his observatory in Scotland in 1827, after a failed attempt to reinstate Rumker at the observatory in 1827, Dunlop returned as the Government Astronomer in 1831.

[Music – Conflict fades]

[Image – Parramatta Observatory]

[Image – Dunlop’s chair]

By this stage, the observatory is was in poor repair, but Dunlop, a serious and diligent man, then spent many hours alone in the cramped and damp observatory over the next fifteen years, seated on a piano chair, carefully observing and recording the night skies.

[Image – Dunlop’s gravestone]

Dunlop’s dismal working conditions affected his health, and he became increasingly unable to work. In 1848 the observatory was closed permanently. Dunlop succumbed to his health conditions and died, in 1848, at the age of 55.

[Image – Catalogue of stars]

The Catalogue of Stars had been published in 1835. Tragically, in years to come, the recordings so meticulously by Dunlop in Parramatta from 1831 onward were found to be inaccurate due to the observatory’s increasingly aged and faulty telescope. The majority of Dunlop’s scientific recording from this time were useless and were ultimately discarded.

[Image – Sydney Observatory]

However, in a positive post-script, before his death, Dunlop advocated passionately for the establishment of a new observatory on the site where the Sydney Observatory was constructed in 1857, and still stands.

[Music – Space reprieve]

[Image – Remnant stones in Park]

All we see now of Governor Brisbane’s momentous plan to construct and operate a scientific observatory to study and record the Southern Skies are the eroded piers of the transit telescope in Parramatta Park, and the handful of surviving Catalogue of Stars volumes.

[Image – Stones in the Park photograph]

These remnants provide tangible evidence of an ambitious scientific endeavour that initially brought great success, but was ultimately undone by a lack of investment and resources, and further sabotaged by personal politics.

[Image – Star catalogue]

However, this admirable early scientific endeavour is captured in the personal and fascinating story of the birth of scientific astronomy in Australia is recorded and written in Parramatta’s stars.

[Credits pages]

[National Science Week logo]

[City of Parramatta Council logo]

[Music – Space fades]

End