Around 1839 Sydney opened a new asylum for destitute women and the insane at Tarban Creek near Gladesville but hopes this would solve the colonies problems for this group proved short-lived.[1] Instead the numbers of destitute women, and people with mental health issues continued to grow and by 1846 the Tarban Creek Asylum was over crowded.

In contrast the stopping of transportation to New South Wales and problems with the facilities at the ‘female factory’ meant there were only 250 women in the ‘female factory’.[2] This combined with the ongoing demands to spend money wisely, impelled the Colonial Government to look at converting the ‘female factory’ into an asylum.[3]

Change was clearly in the wind and the falling numbers at the factory saw Edwyn Statham, the last superintendent of ‘female factory’ have his position abolished in 1848. But perhaps this wasn’t such bad news for Edwyn as he, and his wife, were immediately appointed to superintendent to the ‘Parramatta Lunatic Asylum’. Positions they held until around 1878, when the name and administration changed.[4]

There was clearly room at the factory for more inmates and pressure on existing asylums made it inevitable that some should be moved to the newly named ‘Parramatta Lunitic Asylum’. The only issues appears to have been what kind of patients could the current facilities hold and what modifications would need to be made to take more.

In 1849 Dr Patrick Hill chaired a committee to consider locations for ‘convict lunatics’. He suggested that while the ‘female factory’ could really only deal with lunatics of one sex, the rest of the institution could perhaps take 50-70 male mental health patients.[5] Hill further suggested Parramatta become the institution for ‘uncurables’ of both sexes.[6]

On 18 July, 1849, Governor Fitzroy released an article on the Colony’s finances in which he out lined the following

… it is the intention to remove from Tarban Creek to the building at Parramatta, known as the Female Factory, incurable chronic lunatics. This arrangement, urgently required as a means of desirable classification and of relieving the present greatly overcrowded state of the Asylum, is also a measure of economy, as it will save the expense of upwards of £3000 required by the Superintendent at Tarban Creek, for the accommodation of the increased number of lunatics, now under his charge; no increase is anticipated in the expense of provisions and contingencies, beyond that hitherto provided for the establishment at Tarban Creek. By relieving the Asylum of all the chronic cases, it is confidently hoped that its efficiency as a curative establishment may be materially improved.[7]

This process went ahead and the new arrivals were fitted into the existing buildings and in 1850 the site was officially became the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum.[8] These quickly revealed their inadequacies which had to be overcome by the minor works and extensions as more and more patients were squeezed into the old factory grounds. In 1852 Patrick Hill became the first Surgeon Superintendent of the Asylum, but this appointment was short-lived as Hill died soon after and was replaced by Dr Richard Greenup.[9]

In 1855 the asylum acquired twenty-three acres from the Government Domain, on the western side of the river, for use as a farm, and a further 6 acres were acquired for private access.[10] In 1856 Dr Greenup requested a steam boiler to heat the buildings instead of using open fires which could be dangerous for patients.[11] A 30 yard section of the poorly built sixteen foot high wall separating the refractory women from the gardens fell down 6 November 1856. This was later replaced with a wooden fence.[12]

But all of this did little to change the ongoing need for accommodation and treatment areas designed for asylum inmates and not convicts and criminals. In fact it appears that throughout the 1850s most of the new arrivals were made up from the destitute and low risk mental health patients.[13]

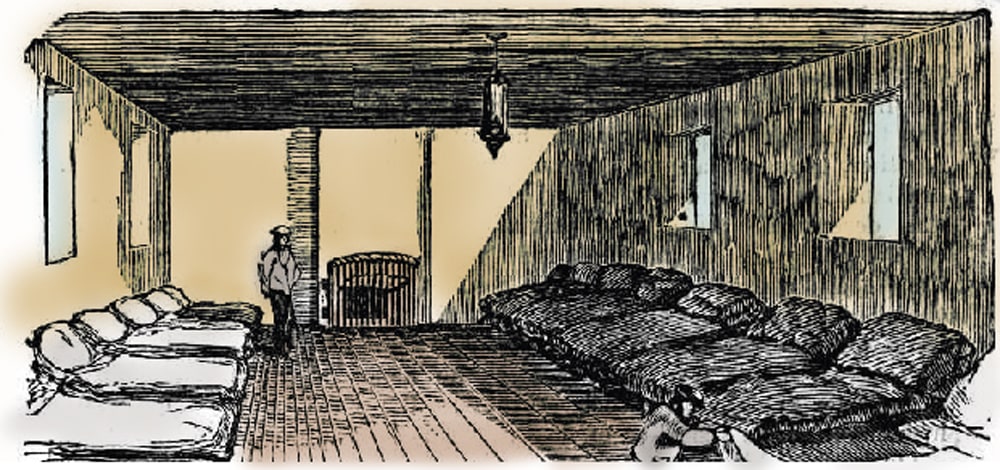

In 1861, the first major addition was built on a site to the north eastern side of the main entrance. Often referred to as the ‘Criminal Lunatics Building’, this was a new block of cells to house the criminally insane separately from the other patients.[14] By this time Superintendent Statham was looking after about 200 male patients while Mrs. Statham looked after around 200 females.[15] Given the following description made by visitors in May of that year they were clearly doing a reasonable job given their limited resources,

[We] entered the grounds of the asylum, this pre dates extensions, a warm pleasant day and once inside the inmates all made their way to them to talk. … one active little man pushed his way to us and claimed our attention …”Do not listen to these madmen,” he said, “you see these marks prove- the fact,” tearing, open his shirt bosom as he spoke. “I was made Pope of Rome a thousand million years ago, by the Lord Jesus Christ! I made Napoleon King and yet I am kept here locked up with these madmen. [16]

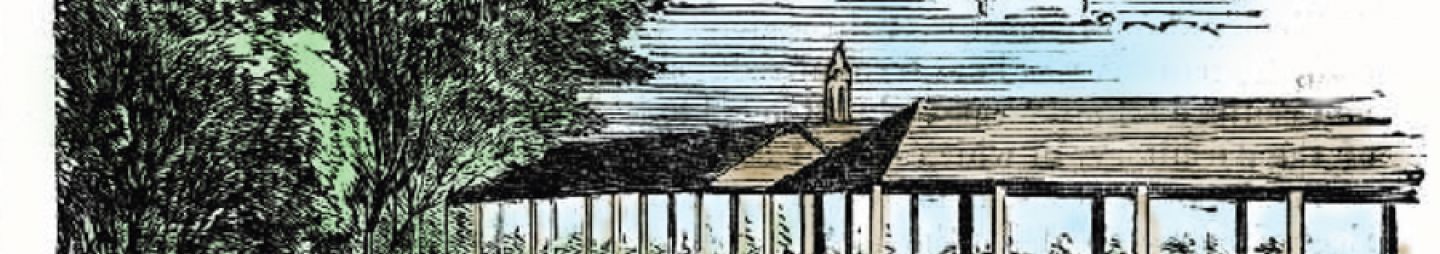

After talking with the inmates in the yard the correspondent commented on the conditions describing the cleanliness of the place, and how the inmates were locked in their separate dormitories at sundown. When they entered the hospital wing they found only eleven patients there. The inmates received a pint of soup, half a pound of meat, and bread, vegetables and tea each day and on fine days the meals were served outside under the large courtyard shed erected for that purpose. Most were granted a liberal amount of freedom during the day but there were extreme cases which needed to be confined. For example they found one man in the courtyard

… whose hands and legs were constantly chained; he was a most violent man – had murdered his wife some years before, and was hopelessly, dangerously mad.[17]

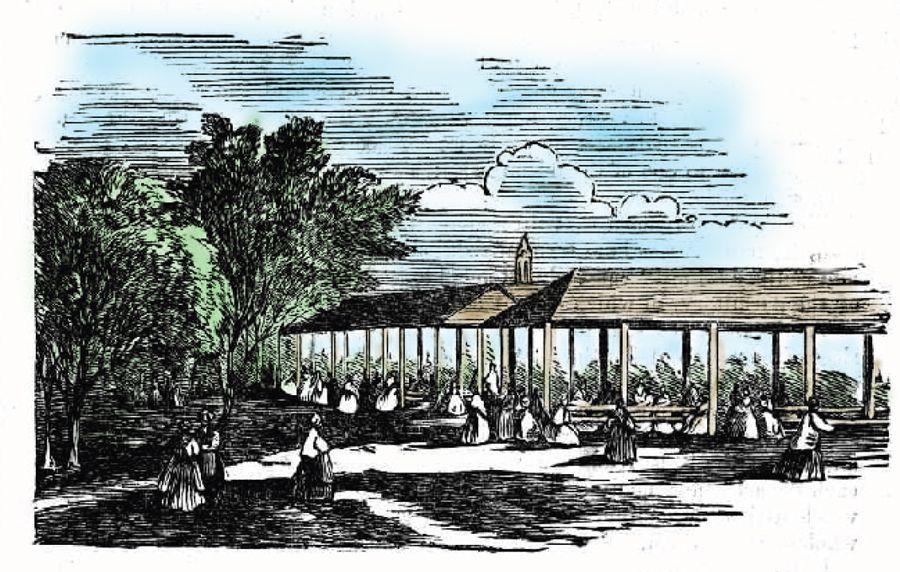

Conditions for the women appear to have been worse as they were the ones occupying the old ‘female factory’ prison cells. But even so they found,

The women were scattered about the courtyard, standing in the shelter of trees, which adorn it, or seated in the covered compartment where, as in the men’s side, their meals are served in fine weather. All was scrupulously clean, some talking and laughing, others gazing silently at us.[18]

In 1864 a second story was added to the Criminal Lunatics building, and the second floor was finished in 1864; and the third between 1868 and 1869.[19] Designed originally with 19 to 20 individual cells, each floor had a ‘keeper’s’ room.[20]

‘Vineyard Farm’

In 1866 the Asylum purchased the adjacent forty-three acre ‘Vineyard Farm’ from George and Ellen Blaxland.[21] This provided an administration building in the form of the old Bett’s family house and gave the administrators enough new land to enable the construction of new purpose-built structures to house male and female patients separately. The first of these was the male weatherboard division (also known as Temporary Asylum, and Central Male Block), built in 1869-1870.[22]

The male weatherboard division –

Between 1869 and 1870 The male weatherboard division was erected on five acres of land separated from the old asylum by narrow band of uncultivated ground. Designed by the Colonial Architect James Barnett it was enclosed with wooden palisading. When the building was reviewed in the Freeman’s Journal in 1877, It was described as being … on the whole well adapted to the purpose for which it was erected.[23]

On the 26 February, 1870, The Sydney Mail, gave a very detailed description of these new premises which were managed separately by Superintendent Dr Wardley, and Mr. J.Rr. Firth, Assistant-Superintendent,

… entering the exercise yard by a side gate at the southern boundary, the visitor finds himself at the end of a spacious verandah floored with cement, and running down the entire front of the building, a distance of over 300 feet. [the kitchen] this is a roomy and lofty chamber, cement floored and fitted with a large patent stove, together with a large copper, etc. At the back of this is a large store, divided by a transverse partition, and to be used, one half for the reception of linen, cutlery, etc., and the other portion for wine, spirits, and such-like articles.[24]

The first men were moved there in the early part of 1870 and although it was originally designed to house 200 patients by 1872 it housed 250.

In 1877, The Freeman’s Journal, gave the following description of the premises,

The pavilion plan is adopted here with the greatest possible success; the inmates and their attendants having free access to all parts of the building without the inconvenience of crossing the yards in all weathers, which is unavoidable in other divisions of the institution. The terrible prison features which I have alluded to as being conspicuous elsewhere are absent in this weatherboard building; there are no bars, no high walls, but a fine area of land, which is neatly laid out as an immense flower garden, and merely enclosed in front by an open paling fence. The building itself is ingeniously designed, and consists of three of four day rooms with dormitories running at right angles. The former can be thrown into one, or partitioned off into separate apartments at pleasure, and consequently some means of classification is at hand did the medical attendant care to avail himself of them.

The division being constructed of wood no whitewash brush is required and the whole place was, sweeter, cleaner, and in every way pleasanter to gaze upon than other portions of the asylum. I have described. The master attendant, who resides at the northern end, has the immediate supervision of the weatherboard building and is assisted by one senior attendant, a cook, a nigh-watchman, and ten junior attendants.[25]

Built on the northern end of the site it was surrounded to the north by a kitchen, stores, and Chief Attendant’s residence, which were added between 1877 to 1880 to support female weatherboard units.[26]

In the 1890s more buildings were added to this area and at some stage before 1930 the Chief Attendant’s residence was pulled down. From 1934 onwards the old male division weatherboard buildings were replaced with brick ones with a similar footprint. These modifications finally ended in the 1960s.[27]

1875-1876 additions

By the 1870s the Asylum had grown to be the largest Government establishment in Parramatta, housing around 800 inmates. Of these 245 were housed in a new wing on land adjoining the main building.[28] Between 1875 and 1876 a range of stone buildings replaced some of the old female factory buildings and improvements were made to the yards. These included one dormitory for 60 patients, 34 single cells and two corridors.[29]

Bn 1878 the males who were quiet, harmless or senile were housed in the ‘weatherboard division’. The buildings were surrounded by a number of open air yard labelled by the 1878 Report as being the, ‘Quiet and Orderly’, ‘Sick Epileptic and Aged’, ‘Noisy and Violent’, and the ‘Intermediate Yard’ which contained an aviary, fountain and trees. [30]

These buildings were all on the north side of the main female factory over the eastern part of the third class penitentiary yard and were referred to as the ‘spinal range’ or ‘Wards No 2’ and ‘Ward No. 3’, they are now referred to as building 104.[31]

Even with all these additions the composite nature of the site, the repurposing of buildings and the pressing need to accommodate such a broad range of psychiatric patients still presented numerous problems for the asylum. Frederick Norton Manning after touring the world to look at asylums elsewhere gave Parramatta a damning review in General report on Asylums, report card, stating,

I have not seen anything so unsatisfactory and so saddening as Parramatta, except at Cairo.[32]

As a result of the Lunacy act of 1878-the ‘Parramatta Lunatic Asylum’ was renamed the ‘Parramatta Hospital for the Insane’ and put under the direction of the Inspector General for the Insane, the first of which was Dr. F N Manning (1878-1898).[33] Manning was replaced by Dr. E Sinclair (1898-1920s).[34]

…. read about the ‘Parramatta Hospital for the Insane and Destruction of ‘Female Factory’

Neera Sahni, Research Services Leader, Parramatta City Council, Heritage Visitor Information Centre, 2015

References

[1] The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 10 October 1835, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/2200584

[2] Kay Daniels, Convict Women, Allen and Unwin, 1998, p.67

[3] Graham Edwards, Factory to Asylum, facsimile copy of typed manuscript in Parramatta City Council, Research Collections, p.3

[4] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 59

[5] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 59

[6] Hill dies in March 1852. Government Medical Officer Letterbook AONSW 2/676, p. 11, cited in Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 59

[7] The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Wednesday 18 July 1849, page 2, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/12902701

[8] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higgenbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p.27

[9] C J Cummins, The Administration of Lunacy and Idiocy in New South Waels 1788-1855, No. 2 of Australian Studies in health Service Administration, April 1968, p.34, cited in Higginbotham, 2010, 27

[10] Kirkby, Sr Map 4807, Feb 1858, cited in Higginbotham, 2010, 31

[11] Lds&PW57/245, Lands and Public Works Correspondence, cited in Higginbotham, 2010, 27

[12] Lds&PW56/404, Lands and Public Works Correspondence, cited in Higginbotham, 2010, 27

[13] C J Cummins, The Administration of Lunacy and Idiocy 1968, p.35, cited in Higginbotham, 2010, 27

[14] T Smith, Hidden Heritage; 150 years of public mental health care at the Cumberland Hospital, Parramatta, 1849-1999, Greater Parramatta Mental Health care Service, Westmead, 1999, p.12, cited in Higginbotham, 2010, 34

[15] Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, Australian Home Companion and Band of Hope Journal, 1 June, 1861.

[16] Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, Australian Home Companion and Band of Hope Journal, 1 June, 1861.

[17] Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, Australian Home Companion and Band of Hope Journal, 1 June, 1861

[18] Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, Australian Home Companion and Band of Hope Journal, 1 June, 1861

[19] T Smith, Hidden Heritage; 150 years of public mental health care at the Cumberland Hospital, Parramatta, 1849-1999, Greater Parramatta Mental Health care Service, Westmead, 1999, p.12, cited in Higginbotham, 2010, 34

[20] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 61

[21] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 60

[22] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 66

[23] The Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, Freeman’s Journal, 1 September, 1877, 17

[24] Lunatic Asylum Parramatta, Sydney Mail, 26 February, 1870

[25] The Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, Freeman’s Journal, 1 September, 1877, 17

[26] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 66

[27] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 66

[28] Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 – 1875), Thursday 17 August 1871, page 3, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/

[29] Lunatic Asylum Parramatta, NSW LA V&P 1875-6, vol 6., cited in Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 61

[30] Colonial Secretaries Special Bundles, Report of the Inspector general of the Insane on Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, 1878, SRNSW, 4/810.3, p.3

[31] Perumal Murphy Alessi 2010:38, cited in Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 61.

[32] Inspector General of the Insane, Report, 1876, p. 10 cited in Higginbotham, 2010, p.38

33] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 59

[34] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 61